HISTORY MAKER: LAURA MARIE LEARY

East Carolina’s first full-time Black student was a ‘mother hen’ for others

It began as a “why not” conversation between two friends, Dr. Leo Jenkins, then president of East Carolina College, and Dr. Andrew Best, Greenville’s first Black physician.

“Why can’t we go on and desegregate this university without a court order?” Best asked Jenkins in the early 1960s, he later recalled in an oral history interview. At that time, UNC-Chapel Hill was under a court order after three young men — Leroy Frasier, Ralph Frasier and John Brandon — were denied entry to UNC due to their race and filed suit.

It was a year after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka ruling, which struck down racial segregation in public schools. Frasier v. Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina applied that ruling to undergraduate education, and a federal court ruled in favor of the students.

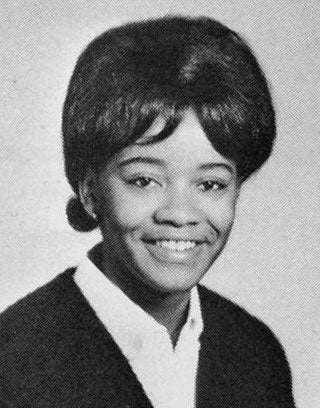

Laura Marie Leary became East Carolina’s first full-time Black undergraduate student in the fall of 1962. (File photos)

“Why can’t we proceed voluntarily, why can’t we?” Best asked. Jenkins had two concerns: ensuring the admittance of a student of high quality, and the possibility of having to call in the National Guard to protect the student, something that had occurred at the University of Mississippi after an incident of mob violence following the enrollment of James Meredith, a Black veteran.

But Best had a plan and a student in mind, one who attended his enrichment classes for high school seniors. He had already talked with the girl’s father, who planned to buy her a car so she could commute.

“If we do it that way, and people get used to seeing a minority face, maybe that will help us change things, bring change about peacefully,” Best told Jenkins, who replied, “Well, I think it’s worth a try.”

Laura Marie Leary, a Vanceboro native and valedictorian of her class at Pitt County Training School in Calico, applied and, following a meeting of the Board of Trustees, was admitted as East Carolina’s first and only full-time Black student in the fall of 1962.

Leary lived off campus her freshman year, and she did not go to sporting events, spend time in the student union or eat with other students. It was a lonely time, she later recollected.

She moved into Ragsdale Hall the following year, though she was without a roommate as the student assigned immediately requested a transfer. But she was no longer alone on campus. Leary was joined by 16 other Black students, some of whom referred to her as a “mother hen” — something she later said she found humorous because of the fear she experienced.

Laura Marie Leary Elliott has a meet and greet at the Ledonia Wright Cultural Center during a 2012 visit.

“Laura Marie went through with flying colors,” Best recalled in the oral history interview, though he said there were one or two incidents in which someone called her the N-word as she walked across campus. “Nothing that happened that she could not deal with,” he said.

Leary persisted, he said, and she represented a crack in the door, with the door continuing to open wider and wider in the years that followed.

She was the first Black undergraduate student to graduate from East Carolina, with her bachelor’s in business administration in 1966.

Leary moved to Bertie County to teach following graduation, before relocating to Washington, D.C., in 1968 and beginning work with the U.S. Department of Justice in an auditing position.

The following year, Leary met Allen R. Elliott after joining a bowling league, and the two married in February 1971, three months after their first date. The couple went on to raise two children, and Laura Marie Leary Elliott retired in 2006 as a senior accountant from the U.S. Department of Treasury, where she had worked since 1987.

An experience she missed out on as an undergraduate came to fruition in 2012, when Elliott returned to campus to speak with students and other alums, participate in the homecoming parade and attend her first East Carolina football game.

At that game, ECU marked 50 years since its desegregation. Elliott was invited onto the field, where Robert Lucas, then chairman of the Board of Trustees, and then-chancellor Dr. Steve Ballard presented her with a plaque.

“Ms. Leary displayed tremendous strength, determination and courage in exercising her civil rights…” it read, adding it was her extraordinary bravery that “helped expand opportunity and equality in public education in North Carolina.”

The recognition came about eight months before she died in May 2013. Elliott’s legacy at East Carolina remains, and the Laura Marie Leary Elliott Scholarship is awarded each year to a student majoring in science, technology, engineering, mathematics or a discipline or field historically underrepresented by students of color.

Sources: UNC’s Documenting American South Oral History Interview, ECU Heritage Hall’s Andrew Arthur Best and Laura Marie Leary Elliott profiles, ECU Digital Collections Oral History Interview, ECU News Services archives and ECU Joyner Library Desegregation website