POST-PANDEMIC CARE

ECU to address post-pandemic mental health

Dr. Sy Saeed, professor and chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine in the Brody School of Medicine, says ECU is poised to help address the influx of mental health care needs during and after COVID-19. (Contributed photo)

Mental health care will become more critical during the COVID-19 pandemic and after it subsides, says one East Carolina University psychiatrist.

Through the North Carolina Statewide Telepsychiatry Program (NC-STeP) based at ECU, the university is poised to help address the influx of mental health care needs, said Dr. Sy Saeed, professor and chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine in the Brody School of Medicine.

“We need to make sure that our communities have access to mental health and addiction services during the pandemic,” Saeed said, “and we need to prepare for a surge in mental health and substance use disorder patients that will occur during the pandemic and in its aftermath.”

Saeed presented an outline this spring to the North Carolina General Assembly’s House Select Committee Health Care Working Group on preparing to respond to mental health needs post-pandemic. The presentation outlined the current situation of mental health care resources in North Carolina, and how the state will need to prepare for the resulting increases.

“Mental health and substance use disorders are common,” Saeed said, “but services have been in short supply even before the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Saeed directs NC-STeP and the ECU Center for Telepsychiatry and e-Behavioral Health (CTeBH). Much of his work focuses on using telepsychiatry to provide mental health care in remote and underserved areas. Established through state legislation in 2013 with $2 million in annual funding, NC-STeP is administered by the ECU CTeBH and is overseen by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Rural Health.

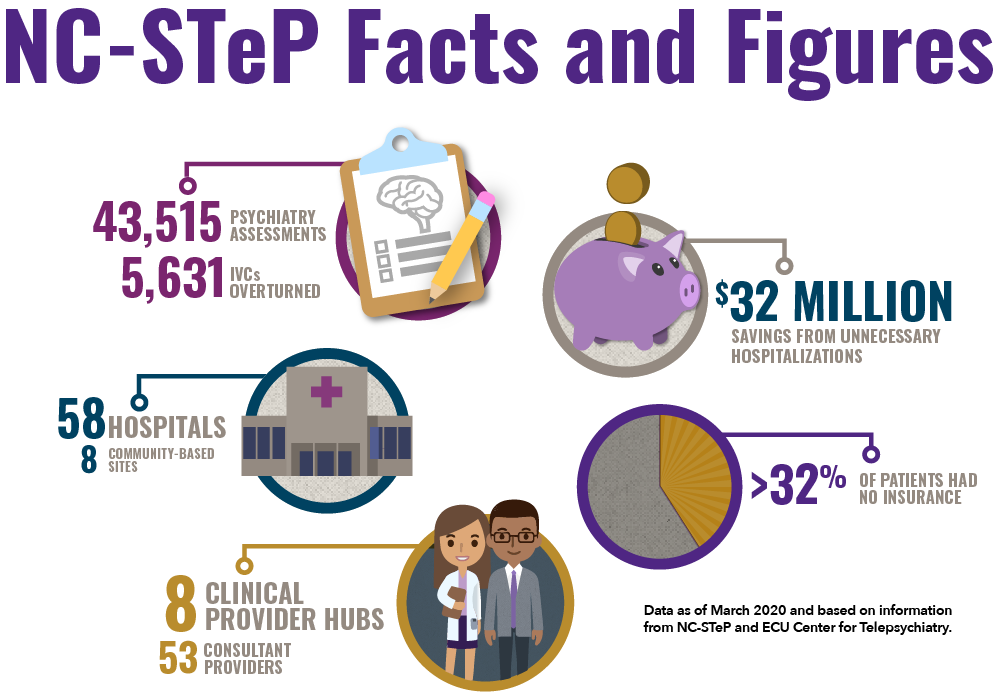

As of March 31, 2020, NC-STeP had 58 hospitals and eight outpatient community-based sites in its growing network and had already provided 43,515 total psychiatry assessments since program inception. The program had also demonstrated nearly $32 million in savings to the state from preventing unnecessary hospitalizations.

Telepsychiatry can be accessed and performed remotely all over the state. When a patient requiring a telepsychiatry consult arrives at a remote referring site, a nurse or other clinical staff sets up a portable cart equipped with a computer, monitor, camera and microphone to establish a secure connection to the psychiatric provider site and introduces the patient to a psychologist, or a clinical social worker who has reviewed the patient’s case.

A patient communicates with a mental health care provider via videoconference as part of the telepsychiatry program in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine at ECU’s Brody School of Medicine. (Photo by Cliff Hollis)

Once the patient’s situation is assessed and relevant clinical information gathered, a psychiatrist evaluates the patient and makes recommendations to the referring primary care physician, who is ultimately responsible for care decisions.

Telehealth services can also be provided directly at patients’ homes from their tablets, computers, or smart phones; they can help bridge connections between patients and providers, even while physical distancing measures are in place.

ECU Physicians unveiled a virtual visit program for the community in April in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, scheduling doctor-patient interactions using video conferencing from the patient’s smartphone or tablet.

Such programs will be vital across the country to address a variety of existing or emerging mental health challenges, other experts add. According to an American Psychiatric Association poll conducted in March, 36% of Americans say coronavirus is having a serious impact on their mental health, and 59% feel coronavirus is having a serious impact on their day-to-day lives.

“The impact of the pandemic on people’s mental health is already extremely concerning,” said Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO), in an April press release. “Social isolation, fear of contagion and loss of family members is compounded by the distress caused by loss of income and often employment.”

Specific population groups are at particular risk of COVID-related psychological distress, according to the release. Front-line health-care workers are particularly affected. In China, health-care workers have reported high rates of depression (50%), anxiety (45%), and insomnia (34%) during the pandemic; in Canada, 47% of health-care workers reported a need for psychological support.

Specific population groups are at particular risk of COVID-related psychological distress, according to the release. Front-line health-care workers are particularly affected. In China, health-care workers have reported high rates of depression (50%), anxiety (45%), and insomnia (34%) during the pandemic; in Canada, 47% of health-care workers reported a need for psychological support.

Saeed said state and local partnerships and collaboration are key to utilizing existing resources and creating innovative models of care that include services and providers such as community-based mental health providers, primary care providers, health department clinics, federally qualified health centers and other experts and resources that are able to meet patients’ needs. NC-STeP, he said, is accessible to participating providers and can be used as a central point for care coordination.

As health care delivery systems have shifted to distance and telehealth visits, telepsychiatry can provide a framework for long-term changes in face-to-face interactions between patients and providers.

“Telemental health services are perfectly suited to this pandemic situation,” Saeed said, “giving people in remote locations access to important services without increasing risk of infection.”