FIVE YEARS OUT

More Brody graduates stay put in primary care fields

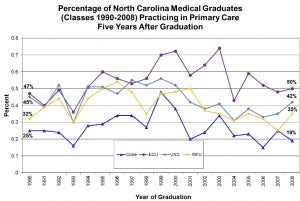

Five years after they graduated, 35 of the 70 members of the Brody School of Medicine’s Class of 2008 were practicing primary care medicine. Among the four medical schools in North Carolina, that’s the best rate of producing the kind of doctors the state needs most, according to an annual report presented Oct. 24 to the University of North Carolina Board of Governors.

Brody’s 50 percent rate of retaining its graduates in primary care fields five years after they graduated compares with 42 percent for UNC-Chapel Hill, 35 percent for Wake Forest University and 19 percent for Duke University, the report said.

Brody doctors also are more likely to remain in North Carolina to practice medicine. The report noted that 46 percent of Brody’s Class of 2008 were practicing medicine in the state in 2013. That compares with 37 percent for UNC-Chapel Hill, 29 percent for Wake Forest University and 17 percent for Duke University.

Producing more doctors who practice primary care medicine is a long-standing policy goal for North Carolina.

The General Assembly in 1993 passed a law requiring the state’s medical schools to adopt plans to persuade more of their graduates to enter primary care medicine.

The law says the medical schools at ECU and UNC-Chapel Hill should aim for 60 percent of their graduates choosing primary care residencies. The goal is 50 percent for Duke and Wake Forest. Primary care medicine includes family medicine and the related fields of pediatrics, internal medicine and obstetrics/gynecology.

Sixty-five percent of Brody graduates selected primary care residencies in 2011 and 69 percent in 2012. The percentage fell to 58 percent in 2013, in part because Brody’s class size expanded to 74, according to a related report prepared for the Board of Governors in February.

The American Academy of Family Physicians repeatedly has ranked Brody as among the best in the nation at producing graduates who choose primary care residency positions.

Between 1999 and 2009, East Carolina sent a higher percentage of medical graduates into training as primary care physicians than any other school in the country, according to the academy.

Brody excels at producing graduates who choose to practice primary care in rural areas because that’s where it recruits its students, said Dr. Paul Cunningham, dean of the Brody School of Medicine. Brody only admits students from North Carolina.

“Living in a rural area requires somebody who has that desire– the missionary’s zeal, I call it–to work in that environment. We recruit from rural areas so they are already familiar with that environment.”

As it has in prior years, the report concludes that it’s difficult for the state’s medical schools to persuade graduates to establish primary care practices in rural counties. North Carolina has 54 rural counties, about half of which are east of Interstate 95.

This year’s report sounds a louder alarm.

“With the exception of East Carolina University medical graduates, the interest in primary care has declined among medical school graduates in the state,” the report concluded. “This decline matches a national trend, but needs to be monitored since a number of counties, particularly in rural and economically depressed areas of the state, are reporting increasing shortages of primary care physicians.”

Out of the 70 Brody doctors who graduated in 2008, nine were practicing primary care medicine in a rural North Carolina county in 2013, the report found. To put that number in context, of the 419 graduates of all four N.C. medical schools in 2008, only 16—including the nine Brody graduates–were practicing primary care medicine in a rural N.C. county five years later.

That’s an improvement over the prior year, when only seven of the 411 graduates of N.C.’s medical schools in 2007 were practicing primary care medicine in a rural county in the state five years later. Of those, four were Brody graduates.

However, “North Carolina’s rural areas continue to have a higher supply of physicians than comparable rural areas elsewhere in the country,” the report said.

The report raised a red flag about the future availability of residency training programs. It noted that graduates of Campbell University’s School of Osteopathic Medicine will begin seeking residencies in 2017, which will increase competition for a constant number of available slots.

The report also warns that the number of community-based primary care physicians willing to offer hands-on training to medical school students “has become very tight in the last year.” These clinical rotations with preceptors, as community-based doctors are called, are the first time many med school students have hands-on experience with patients.

“If you increase the number of graduating students and do not increase the number of practicing physicians who will help train them, then you have a real problem,” Cunningham said.

Dr. Warren Newton, director of the N.C. Area Health Education Centers (AHEC), said access to good health care continues to be a problem in rural and underserved communities. Attracting primary care doctors to those areas is difficult and some rural hospitals are in danger of closing, he said.

“A key barrier is the lack of community based primary care residencies,” Newton said. “Attending an AHEC residency increases the odds of (a recent medical school graduate choosing) primary care by 50 percent and if the person goes to a North Carolina medical school, the percentage goes up more,” he added.

Finally, the report raised concerns about the growing trend of hospitals acquiring medical practices. “Most of these health care systems have not developed workforce strategies which will support a primary care and population health infrastructure,” the report concluded.

The Board of Governors report was compiled by N.C. AHEC and the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at UNC-Chapel Hill from data submitted by the state’s four medical schools.

ECU family medicine physician Dr. Susan Keen and Brody medical student Demetria Watford chat following a procedure on a patient.