Brody achieves state goal for graduates choosing primary care

GREENVILLE, N.C. (Feb. 4, 2013) — In a healthy sign for the state’s future supply of primary care doctors, 69 percent of last year’s graduates of the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University chose residencies in that field of medicine, according to a University of North Carolina Board of Governors annual report released in January.

Sending 49 of the 73 members of its Class of 2012 into likely careers in primary care medicine satisfies a long-standing policy objective set for ECU’s medical school by the N.C. General Assembly. A 1993 state law addressing North Carolina’s chronic shortage of primary care doctors says Brody should aim for 60 percent of its graduates choosing residencies in that field. Primary care is defined as family practice, internal medicine, pediatrics and obstetrics-gynecology.

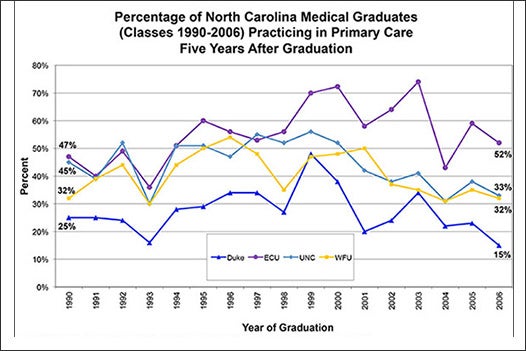

ECU did not achieve the 60 percent goal in the three previous years. However, it has exceeded the goal 13 times in the past 22 years, achieving a high of 77 percent choosing primary care residencies in 2005, according to data tracked by the Sheps Center for Health Services Research at UNC-Chapel Hill.

The law established the same 60 percent goal for the UNC-Chapel Hill School of Medicine. The report said 51 percent of Carolina’s 165 graduates in 2012 chose a primary care residency. The state assigned 50 percent targets to the medical schools at Duke University and Wake Forest University, which are private schools. Duke saw 42 percent of its Class of 2012 chose primary care while 33 percent of Wake’s 2012 graduates did.

While all four medical schools have initiatives encouraging students to aim for a career in primary medicine, officials say cultural trends and a cap on Medicare reimbursements to hospitals for residency programs are making the job more difficult. Primary care doctors usually work longer hours and earn less than doctors who choose a specialty, like surgery. “Students are increasingly gravitating to specialties that allow them to control their hours and have less call on nights and weekends,” the report said.

The Board of Governors report said that with the exception of ECU graduates, interest in primary care has declined among medical school graduates in the state.

“The numbers for Brody in these reports usually look better than the other three medical schools, but this year stands out,” said Dr. Tom Bacon of Chapel Hill, president of the N.C. Area Health Education Centers and executive associate dean of the UNC-Chapel Hill School of Medicine. “ECU started out with a commitment to train primary care doctors, and that continued commitment is still evident.”

“We don’t really deserve that praise,” said Dr. Paul Cunningham, dean of the Brody School of Medicine. “That is what we’re supposed to do. That’s precisely the mission the school was created to serve.”

He credited the ECU Family Medicine Center, which opened in 2011, as a factor in the rebound in ECU’s numbers. “Who could train in such a wonderful facility and not be attracted to primary care?”

In a recent presentation to a medical gathering, Cunningham noted that since 1980, 60 percent of graduates who completed a family medicine residency at ECU are still practicing medicine in North Carolina today. Cunningham noted that 98 of them, or 30 percent, are practicing east of Raleigh.

The Board of Governors report specifically tracks where graduates of the state’s four medical schools are five years after graduation and the type of medicine they are practicing. Of the 67 BSOM graduates in 2006, 35 were practicing primary care medicine, either in North Carolina or another state, in 2011. ECU’s 52 percent primary care retention rate compares to 33 percent of UNC-Chapel Hill’s 141 graduates in 2006.

Although it is the youngest and the smallest in enrollment of North Carolina’s four medical schools[t3], Brody graduates now account for 26 percent of all doctors practicing in North Carolina who attended medical school here, up from just 7 percent in 1990. Carolina-trained doctors account for 42 percent of all physicians in the state who trained here; Wake Forest contributes 24 percent and Duke 8 percent.

However, graduates of North Carolina’s medical schools account for only 25.3 percent of all physicians licensed to practice in the state, according to 2010 data compiled by the Sheps Center. Doctors who attended medical school in another state or Canada made up 51.6 percent of North Carolina’s doctors. International medical graduates made up 16.7 percent, according to the Sheps data.

The Board of Governors report focuses on rural residents’ access to primary care medicine. Data indicate that of the 408 graduates of the state’s four medical schools in 2005, only 10 were practicing primary care medicine in a rural North Carolina county in 2011. Of those 10, four are Brody graduates, four are Carolina graduates and two are Wake Forest graduates, according to Katie Gaul of the Sheps Center staff.

North Carolina’s rural residents have a slightly better chance of seeing a doctor than rural residents in other states. Here, there are 12 doctors per 10,000 rural residents, which compares to the national average of 11.4 doctors per 10,000 rural residents, according to AHEC data. Bacon cited that statistic as proof that North Carolina’s legislated interest in producing more primary care doctors is paying off.