Raising the Brainpower Bar

Project HEART helps teens aim higher

The questions fly in Learning Center 343 at East Carolina University’s Science and Technology Building.

Corey Monaghan, 23, a tutor for Project HEART, is trying to unlock a better understanding of a basic chemistry process.

“What are the characteristics of condensation?” he asked.

His pupil hesitated.

“Think about it,” Monaghan said. “You’re sitting outside on a warm day with a cold soda, what’s happening to it?”

More hesitation.

“In condensation you’re forming water, so where is that water coming from?” he asked.

Project HEART stands for High Expectations for At-Risk Teens. For 10 years this program has placed tutors in schools, on college campuses and in afterschool programs to help high-risk kids in eastern North Carolina.

It’s an AmeriCorps program — the only one of its kind in the state — based in ECU’s College of Education. Chancellor Steve Ballard cited its work in his February State of the University speech. He used its accomplishments as an example of how ECU changes lives and transforms the rural region it serves.

“While institutional reputations usually depend on such factors as federal support for research and the size of the endowment, the impact of a university comes from what we do for people and communities,” Ballard said.

‘A service you provide’

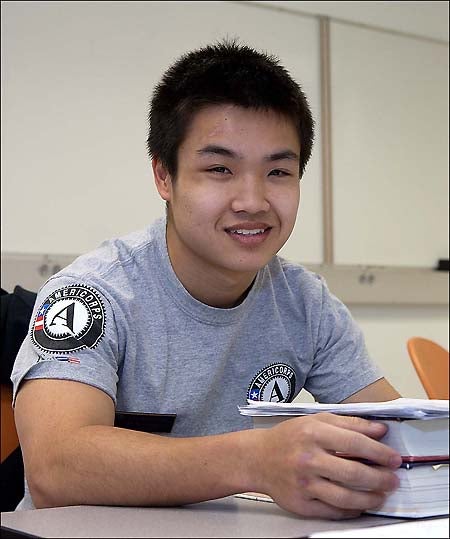

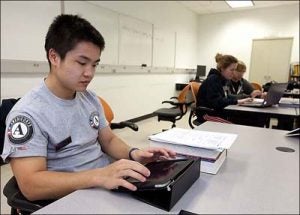

“It has changed my view of how I will approach being a doctor,” said Alvin Tsang, 21, a Project HEART tutor, psychology major at ECU and aspiring student at the Brody School of Medicine. “It’s really not a job; it’s a service you provide.”

Project HEART aims to help struggling students stay in school, graduate, go to college and return to their community to help others. Since the program began in 2000, its tutors have worked with more than 20,000 students in as many as 10 counties in the east. And, more than 5,000 college and high school students have served as “members,” as tutors are called, committing up to 900 hours of time in a year.

In 2010, AmeriCorps selected Project HEART as one of the 52 most innovative programs in the nation.

Project HEART tutor Alvin Tsang offers help that can keep high risk students in school.

“We really have developed a model that works,” said Dr. Betty Beacham, the director. “We’ve had the time to do that which is really good, and somewhat rare.”

The test scores of teens served track a growing record of success. In its first year, 48 percent of the elementary and high school students served by Project HEART passed end-of-grade tests and were promoted, said Beacham.

In 2010, more than 98 percent of elementary and high school students passed end-of-grade tests and were promoted. Since 2005, that rate has remained at 97 percent or higher.

Strong community partnerships and the program’s personal, coaching-based approach are the keys, she said. “I think the relationship our tutors build with the kids whom they serve is a dynamic piece of what we do,” said Beacham.

Project HEART tutors work in small groups. In orientation they get a bag of instructional tools and learn how to apply them. They get introduced to differing learning styles so they can recognize them and reinforce instruction.

The focus is on science and math, with the expectation those literacy skills will transfer to other subjects, Beacham said.

“We are trying to take that child where he or she is and build that piece.”

Training the region’s leaders

The program also teaches its young tutors how to be leaders and build in them a habit of service and helping others.

“The expectation is that they are going to internalize this and they are always going to give back to their communities, they are going to be the leaders in their communities,” said Beacham.

In the learning center, Monaghan works with a college student one on one, writing on the board, pulling out books, sitting down with her. He searches for direct ways to get across how condensation works.

“What state is water?” he asked. “It’s going to be liquid,” his pupil answered in a low voice.

“Good,” he said. “That’s right.”

At the next table Tsang waited for potential pupils to arrive. “If you can help someone else figure out how to figure out their problems, then you know you understand the information,” he said. “If I understand it one way and someone else understands it another, I have to be able to communicate in the way they understand.”

Madison Mayo, 18, of Battleboro is a senior at Rocky Mount Senior High School. He helps tutor algebra I students as a “minimum time” Project HEART member. He said explaining things is the hardest part.

“To be effective you have to be more receptive to what they are receptive to, and if they are not receptive you have to alter your methods,” he said.

He plans to attend the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, eyeing a career in exercise and sport science but keeping his options open. Whatever path he chooses will include lessons from Project HEART, he said.

“It’s opened my eyes and helped me see I can do a lot more than just sit in the classroom,” he said. “I can get involved and help other people with my involvement.”

Stefon Johns, 18, a high school senior in Goldsboro who plans to attend ECU, serves as a tutor in Wayne County. The experience has taught him the toughest cases often are the people you help the most.

“I have learned that once you open up those few people they become the easiest and most willing to learn more of what you have to say,” he said.

A statewide model

Beacham sees Project HEART’s second decade as a time of expansion. She wants it to become a statewide model.

“I would like this program to be accessible to every child across our state who is not succeeding in school,” she said. “We are beginning. Next year is our first entre.”

In the 2011-2012 academic year, Project HEART will add numbers and counties. Beacham has planned for 170 tutors: 50 college students and 120 high school students. The program will serve eight counties in the region instead of five, adding Edgecombe, Halifax and Greene.

Meanwhile, the more than $757,000 in federal funding for the project is not likely to expand and could shrink. That money pays three program coordinators, underwrites a $540-a-month living stipend for tutors with what is called a “half-time” service contract and supports a $5,400-a-year education award those Project HEART members are eligible to receive.

The local match required for that money comes from in-kind contributions and small payments from school systems served. It is equally uncertain. Yet that doesn’t deter Beacham. Shepoints out there are examples of statewide AmeriCorps programs funded at the national level.

Project HEART’s approach also mirrors the school reform approach the state Department of public Instruction uses for low-performing schools, she said. The state offers so-called “transformation” coaches for school administrators, central office workers and teachers.

“What I didn’t hear was a coach for the kids,” she said. “To complete this circle, this is what I think we need, and this is what I think Project HEART can bring to the table.”

For tutors such as Tsang, the biggest impact of the program is the personal growth of those who serve.

“It’s not about a paycheck or a salary,” he said. “It’s about you wanting to help other people.”