A HAND UP

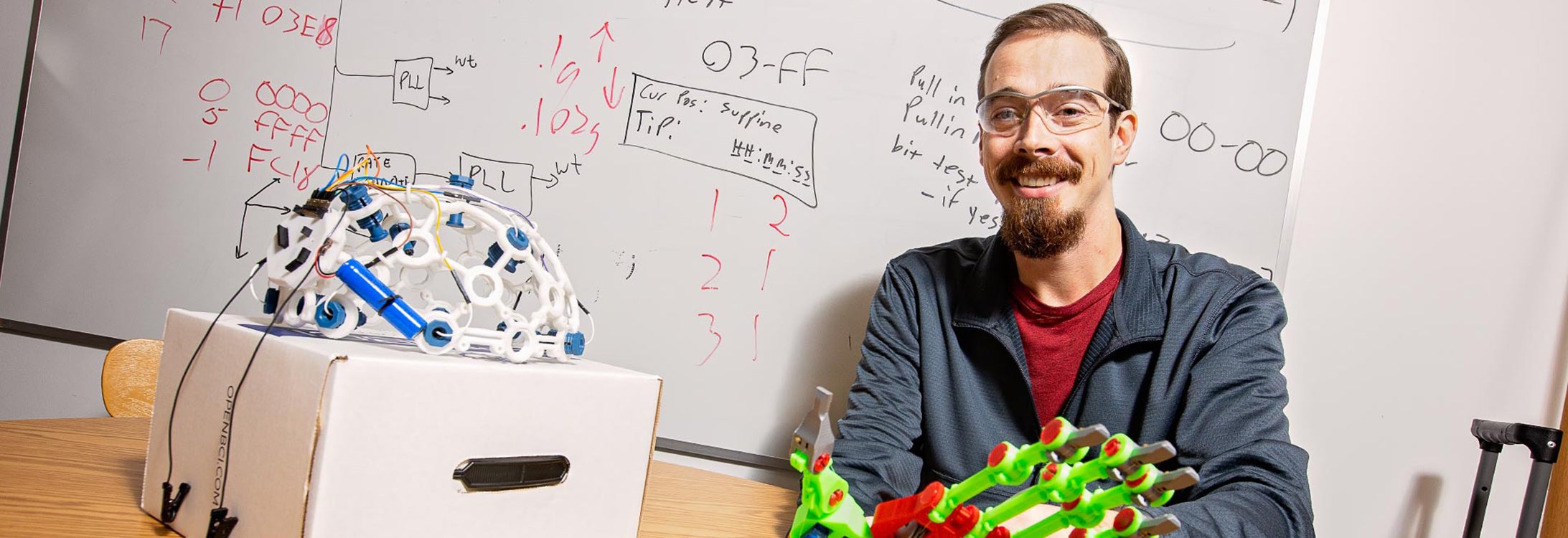

Engineering student and Navy veteran Nicholas Hill is building an affordable prosthetic hand

When you see Nicholas Hill’s experimental prosthetic hand for the first time, it’s just too easy to crack a joke about the upcoming “Terminator: Dark Fate.” It looks that much like a Skynet prototype.

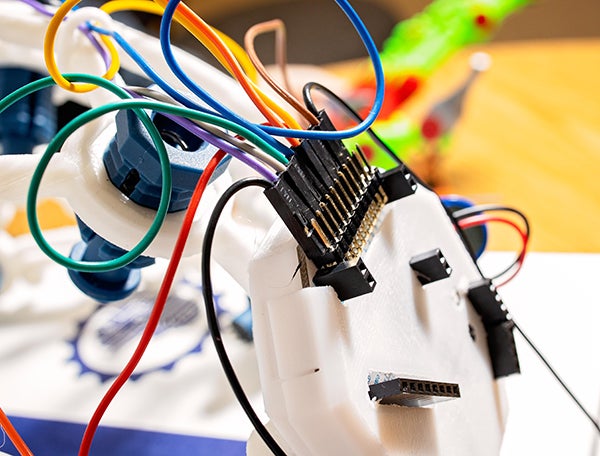

But it isn’t. Instead, it’s a functional 3D-printed hand Hill, an East Carolina University engineering student, made at home, articulated by tiny motors and fishing line and controlled by brain waves via an Ultracortex Mark IV headset. It’s intended to be a more affordable alternative for people with a transradial amputation – the partial loss of the arm below the elbow. Hill received a University Research and Creative Activity Award this year of about $1,700 to develop it.

“They’re just really very expensive,” Hill said of similar prosthetics available through the traditional health care system, “and there’s no reason for them to be.” Think about a child with an amputation, he said. As the child grows, he or she will need new prosthetics. The costs can become astronomical.

Today, there are three types of prosthesis for people with this type of amputation:

- A cosmetic prosthesis that is for appearance only and does not move.

- A conventional (or body-powered) prosthesis that connects to the body through a series of cables. By moving the body in different ways, it is possible to move the prosthesis and open and close the artificial hand. Those cost about $10,000.

- A myoelectric prosthesis, the newest and most advanced form, which connects an electronic hand to the muscles in the arm. As the muscles contract, electrodes send a signal to the artificial limb, causing it to move in much the same way as a real hand. These range from $20,000 to $100,000.

Hill is taking this third type a step further, by connecting it to the brain through the headset. A biosensing board refines the signal into a usable control. However, he said, the deluge of data that comes from the brain must be filtered and calibrated to just the desired hand movements. Thus, a muscle-controlled prosthesis is probably more practical for now, he said.

He estimates his design could reduce costs by 75%. Once he has a working model with a tested output, he plans to upload the hand designs and control systems to the e-NABLE group, which coordinates free prosthetic designs and maker workshops with people who need prostheses for an affordable alternative.

Hill spent 10 years in the Navy before enrolling in the College of Engineering at ECU. He’s majoring in electrical engineering, and once he graduates, he wants to pursue a master’s degree in mechanical engineering. After that, his goals are pretty simple.

“Give me some money and a room and let me build stuff,” he said.

Hill got involved in undergraduate research through a lab course with Faete Filho, assistant professor of engineering, that researched solar energy.

“Nicholas is a very motivated student that was particularly interested in prosthetics and its interfacing mechanism with biological systems,” Faete said. “He has seen firsthand while in the military the need for a more accessible technology.”

As the interview winds down, even Hill makes a “Terminator” reference.

“When the robot takeover happens, they’re going to spare me, because I’m the one who built the bodies for them,” he said with a laugh.

Read more research stories: