WALK IN THEIR SHOES

Poverty simulation builds understanding, empathy

More than 50 East Carolina University undergraduate students participated in a poverty simulation on Feb. 8, with the goal of increasing their understanding of the day-to-day realities faced by people with low incomes. Additionally, organizer Tamra Church, health education and promotion instructor, said she hopes they’ll be “motivated to become involved in activities that help reduce poverty in this country.”

ECU students Hannah Allen, Monica Mayefskie, Elizabeth Smith and Courtney Kirchner review details about their family roles.

The students, public health/pre-health or social work majors, spent the afternoon grouped in families, experiencing scenarios based on real experiences. A ballroom at the East Carolina Heart Institute became “Realville,” with chairs grouped into family units. Tables lining the walls became a bank, a school, a pawnshop. And a local “criminal element” roamed the pathways, avoiding police patrols.

Some of the families were dealing with unemployment, incarceration and/or teen pregnancy while others were caring for elderly relatives, grandchildren or younger siblings. Several were living in a shelter.

During 15-minute-long “weeks,” they went to school or work, searched for employment and housing, paid bills, and sought needed services, from health care and child care to food shopping and social services, at stations staffed by nearly two dozen community volunteers.

Junior Hannah Allen and seniors Courtney Kirchner and Monica Mayefskie, all public health/pre-health majors, along with junior social work major Elizabeth Smith made up the “Wescott” family, a married couple in their 50s caring for their two young grandchildren.

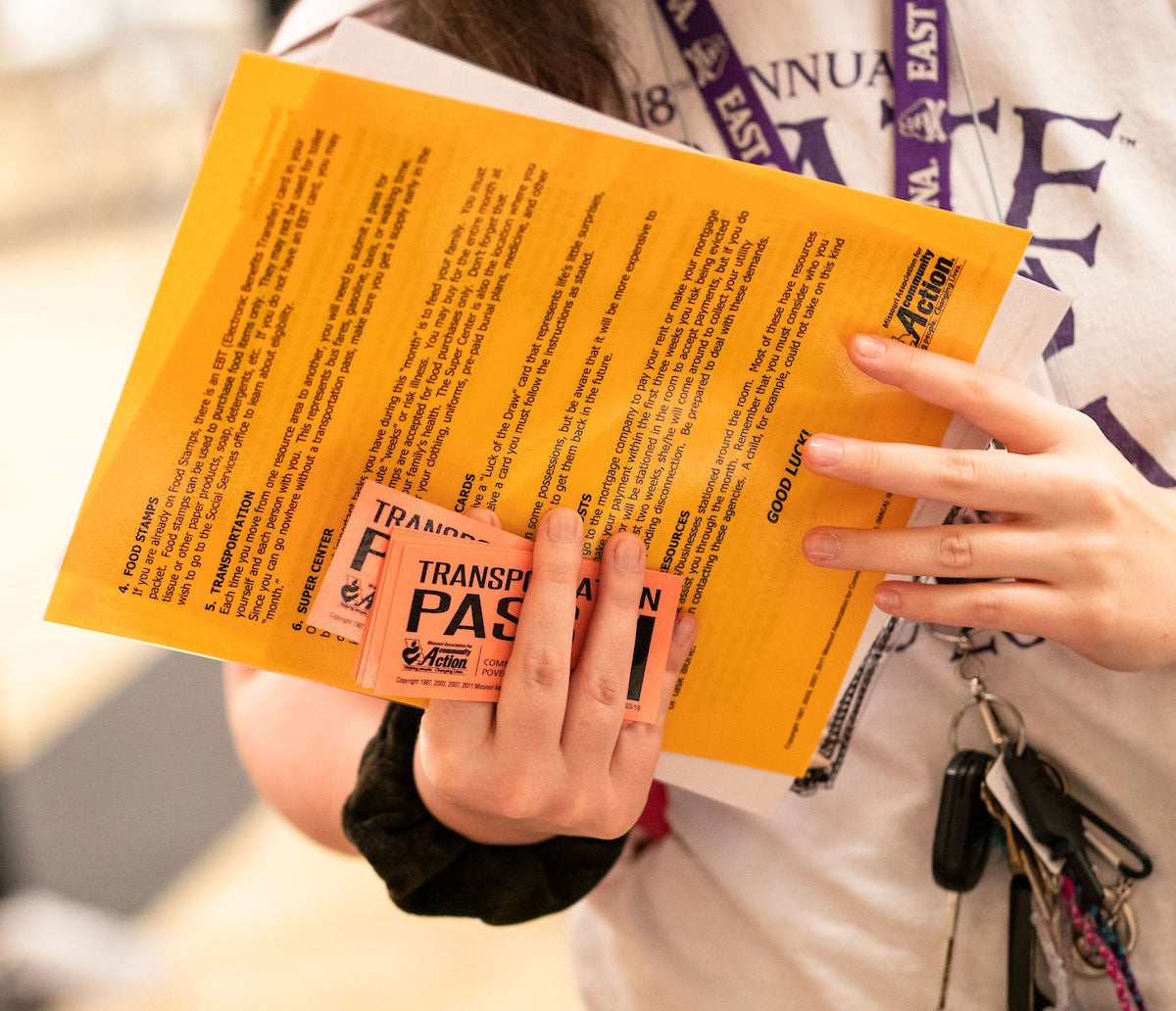

A student holds transportation passes; transportation is a significant challenged faced by families with low incomes.

Their monthly income, from Winona Wescott’s full-time job as a cashier and Warren Wescott’s disability benefit, falls $25 short of their basic expenses. That’s before covering transportation costs, purchasing glasses for their granddaughter and paying small fees for school projects.

And it’s before something goes wrong. When Smith, as Warren Wescott, went to pay the mortgage, she was $20 short. At the next visit to the mortgage collector, she was asked for her receipt as proof of what she’d paid. She hadn’t been given a receipt, so the collector told Smith that they had no record of her payment and the full mortgage payment was due. Allen, as Winona Wescott, made a partial payment. Then, when Smith returned to pay the balance, she still didn’t have a receipt. Over the course of the month, the Wescotts paid nearly double their mortgage, but without paperwork —and with an unscrupulous collector — they still owed several hundred dollars.

Difficulty with the mortgage payment meant there was no money for food one week. “I lied and told my teacher that I had an apple for breakfast because I didn’t want us to get taken away,” reported Mayefskie in her role as the Wescott’s 9-year-old granddaughter. School project fees also went unpaid. “It was embarrassing that we were the only ones who didn’t have our two dollars,” said Kirchner as their 7-year-old grandson.

“This is stressing me out,” says Smith, not only in character. “They don’t tell you all the rules. There’s a lot that I don’t know the best way to get done. I’m so frustrated.”

In a debriefing discussion following the simulation, other students reported similar feelings. Common responses included feeling dismissed or like they were getting the runaround or fighting against unfair forces. One student said, “Our family didn’t eat through the whole simulation. And it wasn’t always a money thing — we just couldn’t get there (to the grocery store).”

“Poverty doesn’t always look like what you think it looks like,” said simulation volunteer Cathy Dixon, a family outreach staffer at the Pitt County Health Department. The simulation helps participants, who’ll likely serve families with low incomes, learn what to look for — and to fully see those in their care.

Volunteer Blace Nalavany, associate professor in the School of Social Work, takes on the role of schoolteacher for the children of Realville.