HURRICANE RELIEF

Brody School of Medicine’s impact felt post-Florence

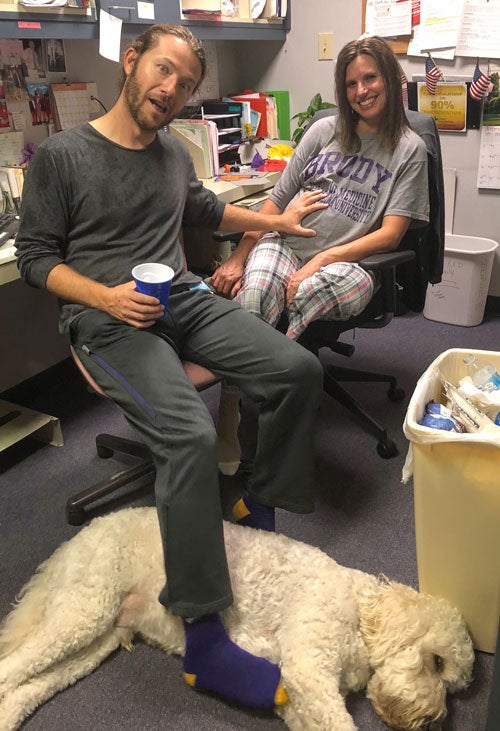

Dr. Todd Kornegay and his 9-months-pregnant wife, Jennifer, slept on an air mattress in his Wilmington medical office in order for him to be able to help treat patients after Hurricane Florence. (Photo courtesy of Todd Kornegay)

When Hurricane Florence brought devastation to the Carolinas, students, faculty and alumni from the Brody School of Medicine made sure they were in position to serve the region’s patients and storm victims – not only in the immediate aftermath of the storm, but for the months and years ahead.

Dr. Todd Kornegay, a 2006 Brody graduate and internist at the New Hanover Medical Group’s central office in Wilmington, slept on an air mattress in that office with his 9-months-pregnant wife, Jennifer, in order to help treat patients at nearby New Hanover Regional Medical Center and a pair of area shelters.

Kornegay’s brother, Jon, and other staff at the Vidant Duplin Hospital in Kenansville treated patients by flashlight and communicated by walkie-talkies in order to keep the storm-battered hospital open to patients who were cut off from the rest of the state by flooding. While the 2008 Brody graduate managed an atypical influx of hospital patients due to the storm, he simultaneously served as the medical director for Duplin County EMS, the operations of which were also extremely hampered by flooding.

On Sept. 19, medical students and residents from Brody – under the supervision of Dr. David Collier, professor of pediatrics at Brody – navigated flooded roadways for seven hours in order to deliver a trailer full of donations to a shelter in Lumberton and then stayed overnight providing medical assistance to storm victims.

Five days later, another group of medical students helped Collier deliver a second trailer full of donations to a regional feeding shelter in Beulaville and then stayed around to help shelter volunteers.

Holding true to Brody’s mission to serve the region’s rural and underserved areas, these examples of disaster response don’t even begin to scratch the surface of the storm-related outreach efforts by the Brody community and the ECU Health Sciences Campus at large in the aftermath of Hurricane Florence.

“I think our Brody-trained physicians and other health professionals that are trained at ECU are really dedicated to this region,” Collier said. “It’s a mission that Brody has stayed true to… and it’s really a testament to the servant leadership in our physician group that gets trained at Brody.”

Wilmington

Dr. Patrick Craig discusses the medical needs of patients he helped treat at John Codington Elementary School in Wilmington, which was converted into a medical shelter in the aftermath of Hurricane Florence. (Photo by Rob Spahr)

Todd Kornegay said he did not want to risk his wife going into labor while sitting in traffic if she attempted to evacuate and have to try to deliver a child on the side of the road. But he said he also made the decision long ago that he would want to be immediately available for his patients if disaster were to strike.

“Every physician has a sense of duty to their patients, but I think at Brody we’re taught an even higher sense of duty toward our patients, especially in eastern North Carolina,” Kornegay said after the storm. “That was sort of engrained in me throughout college, medical school and residency at ECU, so there’s a huge sense of accountability for that.”

As a result, the couple and their cat took shelter on an air mattress in his office. When Hurricane Florence flooded his office, the couple simply moved the air mattress to another room and turned their focus to vacuuming water from the building when he wasn’t working long shifts at the hospital.

By the end of the weekend, Kornegay had also agreed to serve as the medical director of shelters set up at two area schools, including a medical shelter at John Codington Elementary School. There, health care providers treated more than 80 patients for issues ranging from low blood pressure to serious infections. There were hypoxic patients in need of oxygen and patients with end-stage renal disease who weren’t able to get their regularly scheduled dialysis.

“Overall it was a really crazy experience. From being locked down in the hospital, to trying to help out with shelters, to navigating without power. We just really went hour by hour, and tried to stay safe ourselves while trying to keep our patients safe,” said Dr. Patrick Craig, a former chief resident at Brody who’s currently an internist with the NHRMC Physician Group. He worked alongside Kornegay at the hospital and shelters.

Drs. Hayley and Andres Afanador stayed in their Wilmington medical office with their two young children for several days in order to be in position to treat patients during Hurricane Florence. (Photo courtesy of Todd Kornegay)

Husband and wife primary care physicians Drs. Hayley and Andres Afanador, both Brody graduates and members of the NHRMC Physician Group, also opted to stay in the medical office for several days so they’d be in a position to help patients. This decision meant their 2-year-old daughter and 7-month-old son had to stay in the office for the duration of the storm.

“There was certainly some sleep deprivation after helping in the hospital all day and then taking care of them at night, because they weren’t used to not being in their own beds,” Andres Afanador said. “But we were all there together and we were all safe.”

Afanador said his storm experience illustrates why he chooses to surround himself professionally with Brody grads.

“I think the kind of students who are accepted, and who excel, at Brody are the ones who are out there looking out for everyone else in their community,” he said. “They are committed to living and working in eastern North Carolina, and are willing to sacrifice for the people here.”

Just four days after her last night sleeping on the air mattress in the medical office, Jennifer Kornegay – a graduate of ECU’s occupational therapy program – gave birth to a baby boy.

“This is definitely one of those experiences that I’m never going to forget,” Todd Kornegay said.

Duplin County

Duplin County has dealt with more than its fair share of hurricanes. But Jon Kornegay, a Duplin County native, said he’s not sure if there had ever been a hurricane that presented the types of challenges that Hurricane Florence did to the health care delivery system in the county.

After Vidant Duplin Hospital’s main power went out, its main generator also went down – which required staff to work with limited lighting and no phones or air conditioning. The storm then flooded the hospital’s sewage pump, forcing the hospital to enter water conservation conditions, which meant no fresh running water.

“We felt like as long as we were safely able to take care of patients here and we had fresh water we were going to try to stay open as long as we could,” said Jon Kornegay, adding that a local fire department provided a tank of water to the hospital.

“We still had a lot of patients here and we also had a lot of patients still coming to us. Again, Duplin County was an island, we couldn’t get them to other hospitals. So where else were these patients going to go?”

Meanwhile, the county’s EMS units were struggling to access and transport patients due to flooding and strong winds. But before the storm, Kornegay worked with the hospital’s pharmacy to help create special medical kits that included more advanced therapies than those typically available to EMS responders.

“We set these up in some of these areas of concern in the county,” said Kornegay, noting that teams of paramedics, doctors and nurse practitioners stationed throughout the county helped treat patients who couldn’t be transported to a hospital.

Those patients were treated for conditions ranging from acute medical needs to appendicitis and chest pain. But Kornegay said the “save of the week” was made thanks to the last item they decided to put into the medical kits: lytics – drugs that essentially act as clot busters.

The medication is typically not available to EMS units because there are serious risks associated with it. However, when a patient at the Goshen Medical Center location in Beulaville was diagnosed with an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction – a serious form of heart attack in which the coronary artery is blocked and the heart muscle is at risk – Kornegay and Dr. Carl Pate agreed that the lytics would benefit the patient.

“And so we actually gave the lytics in the field there, which was a first for Duplin County, I’m sure. And then fortunately we were able to get a helicopter there… and we were able to fly that patient, who ultimately went to Greenville and got a catheterization,” said Kornegay, adding the patient was able to return home. “That was a lot of entities working together there for that patient to have a good outcome.”

Pate, a family physician who completed his medical residency at ECU, also delivered a baby at the Goshen location in Beulaville during the storm.

Communities in need

Beulaville Mayor Hutch Jones talks with ECU medical students Amber Whitmill, left, and Anna Laughman at Pathway Church in Beulaville, N.C. (Photo by Cliff Hollis)

When the Brody students arrived at Pathway Church in Beulaville with the trailer full of donations, the town’s mayor Hutch Jones made sure to individually thank Collier and each of the medical student volunteers.

“The Town of Beulaville obviously sustained some damage, but the entire region of Duplin County and the surrounding five-county area surrounding us is having a lot of flooding. A lot of folks have lost their homes,” Jones said. “There are communities in this region still reeling from hurricanes two and three years ago, and this was a lot worse. … So it’s going to be months, if not years, before certain communities are going to heal – if they heal.”

Samuel Sumner, pastor of Pathway Church, said the church was operating as a regional distribution center that had supplied food, water, clothing and cleaning supplies to more than 6,000 people in the wake of the storm. This number does not include the truckloads of donations that the church shipped to other facilities in harder-hit communities, he said.

“We’ve seen people who have not only lost their homes, but their farms. Some of them, their houses have literally washed away,” Sumner said. “It has just been very humbling to watch people respond in a time of tragedy like this. And personally, I’ve had two kidney transplants so I’ve spent a lot of time in Greenville. And to see Greenville kind of come back here is good.”

That much-needed compassion for eastern North Carolina has spread nationally, Jones said, with offers for donations and services coming in from several states away.

“At the end of the day, you know that people have the same goal as for the betterment of the community and making sure that they can do for people when they can’t do for themselves,” he said. “It’s even more special when folks that have a direct tie here really step up and will do anything to support their own.”

And the post-Florence response of ECU’s Health Sciences Campus is only beginning, Collier said.

“We’re really looking to see how we can address immediate needs, short-term needs and chronic needs. And what our best response would be and how we can be the most helpful,” he said.

Anna Laughman, a fourth-year medical student who took part in multiple volunteer efforts after the storm, said she was proud to be among so many medical students, residents and faculty who have given so much of their free time, away from loved ones, to help the community.

“I think it’s easy for medical students to be distracted by the academic needs of medical school,” Laughman said. “But in a time of need like this, it’s really humbling and brings back the point that we’re serving a community, not just the illnesses they have.”