Doctor’s three decades of service leaves lasting impact on medical training

Dr. Walter “Skip” Robey retired in October after more than 30 years of service at the Brody School of Medicine, but his lasting legacy will be the medical simulation program he helped pioneer. The program has helped prepare thousands of Pirate doctors, nurses and physician assistants to positively impact North Carolina’s health care future.

Robey’s route to Greenville was not direct, to say the least. He was born in Buffalo and his family moved across the state to Syracuse when he was still young, where he finished high school and then fronted garage rock bands, and his lifelong love of writing and performing music was nurtured.

Studying medicine was always the goal, but he admits that he was caught up in the vibes of the late ’60s, like many young adults, and focused more on working odd jobs and music than his studies. After bouncing around colleges, he eventually got himself on an academic trajectory, graduating from Syracuse University in 1973.

Robey said he quit his band and started working for the county medical examiner’s office while at Syracuse. He used that time to look for institutions that would accept a student with a less-than-direct trajectory path to medical school.

“At that time graduates would go to Guadalajara, Mexico, for their training, but tuition was very expensive, so I considered reputable schools in Belgium and France as an alternative,” Robey said.

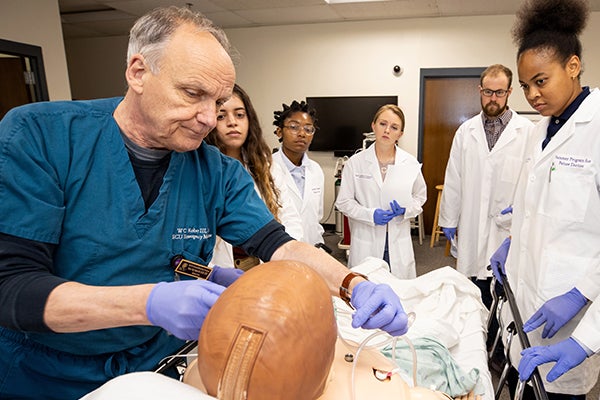

Dr. Walter “Skip” Robey, the recently retired director of ECU’s medical simulation program, demonstrates a medical technique to students at the Brody School of Medicine.

Getting into those French medical schools wasn’t easy, and certainly wasn’t a guarantee — classes were all taught in French, which Robey had a basic familiarity with, but he still required a translator to help with the application process.

Dr. Walter “Skip” Robey stands at the head of a bed in a simulated hospital room while medical professionals examine a simulated patient.

Having not heard from any schools, he hopped on a plane to Belgium a month after graduation from Syracuse to try to get into the University of Brussels. When he was placed on a waitlist there, he made his way to Paris to live and work on his French until he heard from the University of Bordeaux that they would give him a chance.

During his time there, he learned the language by immersion in the culture. Robey not only mastered French and completed his training, he met his wife, Claude, who was also a medical student.

After finishing their coursework in France, the Robeys, along with their first child, moved to the French Caribbean island of Guadalupe where they both completed internships.

After a year on the island, the Robeys moved to northern New Jersey. A hospital there didn’t have an accredited emergency medicine program and wanted him to help achieve accreditation. He was eventually made the residency program director.

“It took us several years to achieve accreditation and our efforts created the first three-year emergency medicine program in the state,” Robey said. “We also established a pediatric emergency medicine fellowship and contributed to a state trauma center designation for the hospital.”

Having completed the mission of getting the program accredited, and with their kids getting older, the Robeys looked for a quieter place to establish their practices and raise a family. In 1994, Skip was invited by the chair of the emergency department at Brody to join the faculty.

“They said, ‘We know you’re coming down as faculty, but could you be an associate residency director?’” Robey remembered. “I said, ‘Sure, OK.’ And so, 11 years later, I stepped down from that position and we started the clinical simulation program initiative.”

Skip and his wife, an endocrinologist who retired several years ago from practice at Physicians East, have three children living in Raleigh and Cary. Two of their children are continuing the Robey health care legacy: One son is a gastroenterologist and Brody graduate, and their daughter is an emergency physician. Another son is an attorney. Eight grandkids keep them traveling to the Triangle for baseball games, birthday parties and other family events, which Robey said is the next step in his career — to be a professional husband, father, grandfather, friend and to continue to write songs.

Medical training and applying it to teaching

Simulation has been a part of medical training since ancient times, and the use of medical simulation to prepare Brody students to become doctors has a rich history, Robey said. In the early days, equipment was rudimentary and opportunities spare.

“We’d use any available equipment and a small conference room or vacant space over in the Department of Emergency Medicine for workshops to teach and practice skills and create simulated scenarios using old mannequins that really weren’t very dynamic, but it all worked,” Robey recalled.

Around 2004, Robey and his team got permission to clear out received grants to purchase Brody’s first dynamic mannequin, and overhaul the room to resemble a clinical space and provide remote video connections.

Dr. Walter “Skip” Robey recently retired as the director of the Brody School of Medicine’s medical simulation program.

With the jumpstart of a mannequin that better replicated a living patient, and improvements to the simulation program came quickly. Robey said his focus in training was always safety — for the faculty and students, and ultimately for the patients they would care for.

“We must make sure that everyone is safe around the patient, including the patient. To do that, we need to train as though we are at the bedside,” Robey said. “Our job is to not damage faculty or our learners. There’s an emotional safety and psychological safety that we need to be concerned with when building scenarios or creating real-life scenarios and situations for training.”

Robey is proud of the physical improvements to Brody’s simulation program, but more so that a range of health care providers are part of the program.

“We work together. If we’re doing collaborative, reality-based, hands-on education, that’s going to extend over into what we do at the bedside,” Robey said. “We have several interprofessional simulation-based education programs involving a variety of health care professions, and they all want to work together.”

Dr. Laura Gantt, professor of nursing and associate dean for nursing support services in the College of Nursing, met Robey when she worked for what is now ECU Health. When she joined the College of Nursing in 2006, she was tasked with growing the simulation program to support training for nurses at all levels of the profession.

“Over the last 18 years, we have collaborated extensively to improve the education of students across the health sciences and the larger campus,” Gantt said. “The development of interprofessional programs for students starts with interprofessional faculty who can work together to develop educational activities. I am proud of what we have been able to co-create.”

Rebecca Gilbird, administrative director of Brody’s Interprofessional Clinical Simulation Program, said Robey has been a great role model and advocate for simulation education.

“He helped me develop my career by teaching me simulation best practices, how simulation can be used as an effective learning tool, and how to advocate for the importance of simulation in clinical learning,” she said. “Due to his support, I now work with the Society of Simulation in Healthcare to help other centers reach those goals.”

Dr. Paul Cunningham, dean emeritus of the Brody School of Medicine, echoed Gantt’s and Gilbird’s praise for Robey.

“Simply stated, Dr. Skip Robey’s indefatigable and passionate vision and work to create practical and up-to-date simulation capabilities here on campus was prescient and just genius,” Cunningham said. “I doubt that we would have the capabilities that we now enjoy without his unflagging passion and work.”

When he retired, Robey had been involved with the simulation program for more than three decades. He hopes the young women and men who have passed through his simulation program take him as an example of what their careers can be — that they can see themselves as still being important to their patients and the students they will train 30 or 40 years hence.

“I don’t know what I’m like in their eyes, but at least they can say, ‘Geez, I can practice that long,’” Robey said.

Robey said he’s fortunate to have achieved many of his professional goals. Not all of them, but most, because of his family’s support and understanding, and because of the people he worked alongside to make Brody’s simulation program a success.

“Every time I come in the simulation center door, I smile and chuckle to myself looking at what we have collaboratively accomplished, and that’s something to be proud of,” Robey said. “I’m a lucky guy.”

What he’s most proud of, though, are the people in his life who have made his career a reality.

“I’ve had some success, and hey, I’ve screwed up plenty of things, but I’ve been kept in the direction that I need to be going by my family, friends and colleagues. And I’ve been fortunate to be able to watch them be successful as well,” Robey said.