ECU’s Nursing Education program trains faculty for community college programs

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention make no bones about the schism in health care outcomes between urban and rural parts of the nation: “rural Americans are more likely to die from heart disease, cancer, unintentional injury, chronic lower respiratory disease and stroke than their urban counterparts.”

Dr. Sara Griffith is a Pirate nurse and chief nursing officer for the North Carolina Board of Nursing. (Contributed photo)

In 2023, North Carolina’s demographer reported that the state had the second largest rural population in the country, nearly 3.5 million people, which works out to about a third of North Carolinians living in rural areas.

One key to overcoming current nursing shortages, and the projected deficits in the coming decades, is masters-level nursing education programs like the one at East Carolina University that prepares experienced nurses to lead programs across the state.

Instructors need a minimum of a master’s level education to teach in community college nursing programs, but many have doctoral degrees, said Dr. Shannon Powell, associate dean for academic affairs in the ECU College of Nursing.

There are different ways for future nursing instructors to become qualified to teach entry-to-practice nursing students, but ECU’s nursing education Master of Science degree is a focused and intentional way to reach the necessary preparation and certification, Powell said.

“A large majority of our own BSN faculty are also graduates of that program, and the program also prepares nurses who want to go into professional development or staff development,” Powell said, adding that clinical organizations across the state need nursing educators who can create and provide training for new nurses and recurring training for existing staff members.

The challenge in bridging the education level gap is often attributed to a simple availability — of faculty to teach students and clinical training sites to give student nurses hands-on training before graduation.

Recently, Roanoke-Chowan Community College in Ahoskie was in serious need of a nursing program director and faculty, which could have left a sparsely populated and medically underserved corner of the state without an ADN program. One of ECU’s nursing education alumni, Stacey Futrell, applied for the director’s position and stabilized a vital hub of nursing education in northeastern North Carolina.

“There really are no words to show how proud I am of this Pirate nurse educator. She gave up other career opportunities to go to this program and work to maintain and improve it because she recognized the vital role this program plays in the health of the local hospital and community. She’s really done a great job,” Powell said. “Their NCLEX scores this past year were very good and the graduates largely contribute to the health of the local rural and underserved community.”

Dr. Kent Dickerson, dean of the allied health and nursing programs at Beaufort County Community College, speaks at a scholarship luncheon at BCCC. (Beaufort County Community College photo)

In recent years, Roanoke-Chowan has consistently tallied first time pass rates above 90% — outside of a dip in nurse licensing exam pass rates during the COVID-19 pandemic experienced by many nursing programs across the state.

Getting nurses into rural health care settings and keeping them there is a real challenge for health system leaders. A 2022 analysis showed that nursing vacancies have an outsized impact on hospital closures, due to a rapidly aging nursing workforce and the increasingly high cost of paying staff nurses. Hospitals and clinics in rural areas are forced to pay travel nurses two and three times the rate as staff nurses, like their urban counterparts, contributing to financial strain on hospitals and clinics serving rural communities.

Dr. Kent Dickerson, dean of the allied health and nursing programs at Beaufort County Community College (BCCC), is another Pirate nursing education program graduate leading a community college program in eastern North Carolina. Dickerson completed his master’s degree in 2008 and doctorate in 2021 at ECU.

Dickerson’s program usually graduates between 35 and 50 new registered nurses, along with 10 to 20 licensed practical nurses (LPN), each year. Close to 85% of Associate Degree of Nursing graduates are employed in or near Beaufort County, and 9 in 10 LPNs remain in the region – and their skills are in constantly high demand.

“Each one of our graduates has two to three job offers before they graduate, at ECU Health Beaufort or the medical center in Greenville,” Dickerson said. “Some go to CarolinaEast in Craven County and some to ECU Health Bertie.”

BCCC graduates also help fill needs outside of hospitals. Dickerson said his graduates work as school nurses and in health departments and nursing homes across their service area of Beaufort, Tyrell, Hyde and Washington counties.

Local community college programs are a lifeline for many potential nursing students who, because of life circumstances, couldn’t attend a four-year institution to become a nurse.

“I have students who are just out of high school, but I also have second career students with families. I have mothers with infants and small families who may be a second career student,” Dickerson said. “We know how important it is for us to serve our community.”

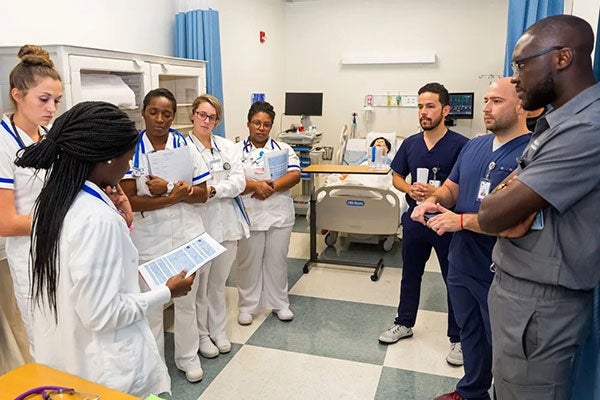

Pitt Community College nursing students interact with Brody School of Medicine students during an interprofessional training simulation in 2019. (Pitt Community College photo)

The cost of a community college education is also a benefit for nursing students. Dickerson said two years and about $10,000 can result in a well-paying job that has immediate and positive impacts on a community without saddling the student with long-term debt.

Dickerson applied to ECU to learn how to teach future generations of nurses, and having a nursing education program close to home was a benefit.

“Not all nurses are good nurse educators, so to have a program here in our region that trains us to set forth procedures and guidelines and helps us understand the importance of research and nursing education is important,” Dickerson said. “It would take them multiple years of experience in the classroom to feel comfortable doing an alternate learning strategy, and the university provides those resources.”

Amy Underhill, deputy health director for Albemarle Regional Health Services in Elizabeth City, which serves eight counties in northeastern North Carolina in desperate need of nurses, said she is grateful that the region has a network of educational paths for nursing students. Underhill also stressed the importance of hospitals and clinics providing clinical training sites for nurses who hail from, and will likely remain in, eastern counties.

“We always look forward to being able to provide students with public health experience during their clinical rotations,” Underhill said.

Dickerson views the community college system as the lynchpin of America’s health care future.

“Our community colleges are graduating 60-70% of the nursing workforce, so if you take that away it will be disastrous for the health care industry,” Dickerson said.

Community College Impact on Health Care

Dr. Sara Griffith, a Pirate nurse and chief nursing officer for the North Carolina Board of Nursing, said community colleges are vital to meeting the health care needs of the state. A North Carolina Board of Nursing report from 2022-23 (PDF) revealed that about 1,800 entry-to-practice nurses graduated from community colleges compared to about 1,100 from four-year institutions.

Dr. Shannon Powell is associate dean for academic affairs in ECU’s College of Nursing. (ECU College of Nursing photo)

“The North Carolina Board of Nursing has requirements for faculty and administration to have certain degree requirements and credentials in order to teach our future nurses,” Griffith said.

There were 273 nursing faculty vacancies in educational programs that prepare nurses — 131 full-time positions and 142 part-time — at the 2022-23 report’s release, Griffith said, reinforcing the growing need for nurse educators.

“Nursing education programs in North Carolina can help fulfill those needs of programs across the state,” Griffith said.

Colleges are innovating how to train and educate new members of the nursing profession, Griffith said. Surry Community College in Dobson, and Gaston College in Dallas, are adopting pathways for high school students to gain their licensed practical nurse education, which Griffith lauds as an exciting step forward in building the nursing workforce as LPNs often progress to complete registered nurse qualifications.

“What that will do is give students pathways to progress into an RN and then get their master’s — developing those seamless pathways — for individuals to work to meet the needs of their community,” Griffith said.

Griffith said she is also very excited about the partnerships that community colleges and four-year institutions like ECU are building with their local health systems to foster a culture of support for the student nurse.

“Surry-Yadkin Works has a program for high school students and is getting them into internships and apprenticeship programs. Duke Health has collaborated with Durham Tech and Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist has developed a partnership with Davidson-Davie Community College. Those are just a sample of the apprenticeship programs that are popping up across the state in order to again drive that pipeline,” Griffith said.

Griffith said the investments that health systems are making in individual students by helping with tuition and paid time off to attend classes, particularly in local community colleges are wise ways to keep one of the most precious resources in health care — the nurse — interested in remaining a part of the team.

Whether standing in front of a community college classroom, or leading online discussions with BSN students in a traditional university program, Griffith said nursing education programs like the one at ECU are critical to ensuring this highest quality education for the next generation of nursing students.

“Nursing education programs are vital for us to be successful in educating our future nurses,” Griffith said.

MORE BLOGS