GAME ON

Pilot study to test, implement coping skills for children with ADHD

A $1.38 million national grant awarded to an East Carolina University researcher will examine how a serious video game may help young adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or ADHD learn academic coping skills.

“Some people describe these as academic enablers, which are skills we teach kids that are not directly related to the content of the class but help them to be more effective at absorbing the content, such as study skills, organization, assignment tracking and note-taking strategies,” said Dr. Brandon Schultz, assistant professor in ECU’s school psychology program and lead investigator of the study funded by the Institute of Education Sciences.

Dr. Steven W. Evans, clinical psychologist in the psychology department at Ohio University, is co-principal investigator on the grant. (Contributed photo)

For the next three years, Schultz and his co-principal investigator, Dr. Steven W. Evans, psychology professor at Ohio University, will design, test, implement and examine the effects of streamlining intervention procedures through the use of a video game for adolescent middle-school students with ADHD. They will compare a group of students receiving video game-enhanced treatment to a control group receiving established school consultation treatments.

“This project represents an important advance in the development of effective intervention programs for adolescents with ADHD,” said Dr. Erik Everhart, interim chair of the Department of Psychology. “The opportunity to implement this project within eastern North Carolina provides an example of the strength of the relationship between the department of psychology and the surrounding schools and community.”

Standard ADHD coping skills – organization, note-taking and study skills – are often taught to children at a very young age.

“The transition to middle school is particularly difficult for students with ADHD due to the increasing demands on organization, study skills and social problem solving,” said Schultz. “My colleague developed the Challenging Horizons Program with those needs in mind, and this project is essentially the ‘gamification’ of that program.”

According to Schultz, kids in elementary school who have ADHD do better because teachers spend a lot of time early on showing kids how to organize a backpack or binder and how to take notes or plan activities. By middle school, there is an expectation that adolescents have learned these skills and therefore the information is not reviewed as thoroughly.

“What we find is that teachers may touch on these topics, but it is more or less a one-time introduction on how to set up your notebook. But for adolescents with ADHD, that simply is not enough,” said Schultz. “If you were to summarize ADHD in one word, that one word would be ‘disorganization.’ That’s the problem with ADHD – disorganization of time, disorganization of materials, disorganization of thought.”

Current interventions between adolescent students and teachers can be problematic.

“Those interactions with teachers and kids can kill a relationship,” said Schultz. “Teachers don’t enjoy it because it requires a lot of time and correction, and kids don’t like it because they feel like they are being singled out.”

The whole idea is to take this part of the ADHD intervention and put it in a video game, Schultz said. The game will encourage kids to get engaged with these interventions, or coping skills; shorten intervention startup times, therefore taking some of the burden off teachers; and improve student-teacher relationships when compared to traditional practices.

The study is considered a development project, and Schultz and Evans hope to show that intervention is feasible, acceptable and satisfactory to parents, teachers and kids.

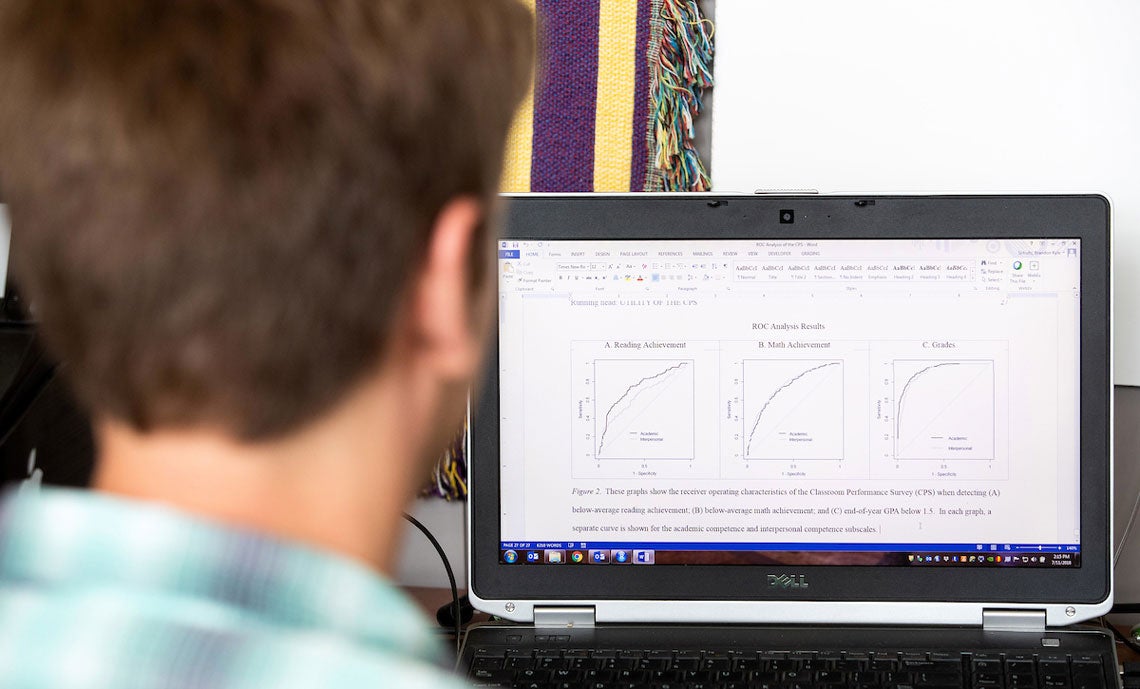

In the first year of the research study, Schultz and Evans will work with Ohio University’s Game Research and Immersive Design Lab to develop a game prototype. (Contributed photo)

Schultz will work with Ohio University’s Game Research and Immersive Design Lab to develop a game prototype in the first year of research.

“They are fantastic,” said Schultz. “They build these incredibly engaging and fun games, and you really don’t even realize you are potentially learning something in the midst of it.”

Schultz and designers at the lab are already thinking about a prototype they can use to acquire feedback from local educators and students.

“To beat the game, you have to come up with a way to organize information in a way that absolutely mirrors what we will be showing them in their book bags and binders. They will even have to sort information they are collecting in a note-taking strategy – main ideas and supporting details,” said Schultz. “All those concepts that we have to sit down and tediously teach to a child, we are going to have the game stealthily do that for them. They won’t even realize they are getting this lesson in the game.”

The game will not attempt to correct a fault, though it may teach children mnemonic strategies. According to Schultz, adolescents may learn ways to memorize lists in the midst of the game in order to beat it and may then be able to apply those skills to actual classwork.

In recent years, Schultz said there has been progress in educational video games, with research showing that some programs can successfully teach content knowledge such as math, science or history.

However, he emphasizes that he is skeptical about a lot of promises made about video games and that, unfortunately, there has been a lot of wasted energy towards developing games that will repair poor memory or increase attention spans.

“I just want to make clear, that is not what this is at all,” Schultz said. “People will see ads on television for games that are supposed to do these things. The research on that is absolutely abysmal. They just do not work. You will get better at playing the game but that’s about it. In short, video games cannot remediate cognitive deficits – at least not yet.”

In year two, Schultz will work with ECU’s Pediatric Outpatient Center to recruit children to participate in focus groups. Three focus groups, each consisting of 25 kids, will play a prototype of the game for 45 minutes and then provide feedback.

Recruitment for the second phase of the project will begin in January and those interested in participating may find more information on Schultz’ website closer to that time.

In the project’s third year, Schultz and Evans will randomly assign 36 middle school students with ADHD to either the video game-enhanced treatment or an established school consultation treatment. Participants will be evenly recruited, with 18 participants from North Carolina and 18 from Ohio.

“We are working with Pitt County Schools and have received principal support to implement the project at E.B. Aycock Middle School and Farmville Middle School,” Schultz said.

According to Schultz, traditional school consultation treatment is considered “best practice” when introducing change in schools. It involves an expert consultant working with teachers to troubleshoot difficulties that arise when new practices are attempted.

For example, teachers implementing a new classroom management technique may meet with a behavior consultant to discuss specific student needs.

Schultz said this type of approach is an interactive professional development strategy that can lead to lasting change and has proven effective in previous research.

If the projected outcomes occur, Schultz plans to conduct an efficacy trial beginning in 2021 to examine long-term academic and psychosocial outcomes.

“Assuming our efforts are successful, we hope to expand the game to both younger and older populations in subsequent studies,” Schultz concluded.

Learn More

If you would like to learn more, visit the Ohio University’s GRID Lab website

Schultz analyzes instruments that will be used to measure the impact of video games. (Photo by Rhett Butler)