BRED AND BREAKFAST

ECU professor raises mosquitoes for disease research

Amenities might not include a home-cooked breakfast, but lodgers are abuzz about accommodations in the third floor lab of East Carolina University’s Carol Belk building.

There, ECU professor Dr. Stephanie Richards serves up an environment conducive to breeding a colony of mosquitoes, which enables her research on how the pests transmit disease to humans.

Richards, assistant professor in the Department of Health Education and Promotion, is trying to determine what makes one mosquito a better vector for virus transmission than another. Her work has demonstrated that biological and environmental dynamics such as mosquito age and environmental temperature affect the mosquito-virus interaction. She needs to cultivate a thriving colony as she continues to investigate those factors.

“We have to get them to keep laying eggs,” said Richards. To do that, mosquitoes must be fed.

On the menu for the colony are meals of cotton balls soaked in sugar water, simulating the nectar that mosquitoes feed on in nature. But females need blood to lay eggs, so they receive an extra helping of cotton balls soaked in animal blood ordered from a supplier.

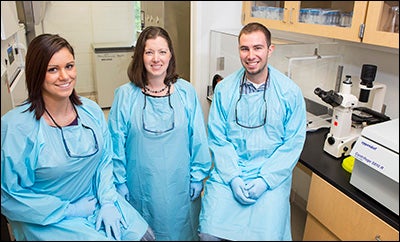

ECU professor Dr. Stephanie Richards, center, works in an ECU research lab with graduate students Caitlin van Dodewaard, left, and Jonathan Harris, right. Richards is conducting research on how mosquitoes transmit disease to humans.

Richards maintains the colony with help from ECU graduate students, including Jonathan Harris of Virginia, who counts eggs, checks survival and blood-feeds the mosquitoes. Graduate student Caitlin van Dodewaard of Renfrew, Ontario works in the lab inoculating cultures with virus and feeding that virus to the mosquitoes.

The mosquitoes are infected with vector borne pathogens that cause dengue or La Crosse encephalitis, the most commonly diagnosed arboviral disease in North Carolina. Arboviral diseases are infectious illnesses transmitted by bloodsucking creatures such as mosquitoes or ticks. Although adults can become infected, severe cases are most commonly seen in children.

Twenty-six cases were reported in 2012, primarily in the western counties of the state. Mild cases are often misdiagnosed as flu-like illnesses and there may be as many as 300,000 infections per year in the nation.

“There are no vaccines for these diseases,” said Richards. “That is why it is so important to prevent mosquito bites in regions where the diseases are endemic.”

Richards said mosquito eradication is not an option. “There are too many of them,” she said. In addition, she said mosquitoes develop resistance to pesticides over time, which is an obstacle to controlling these insects.

One of the biggest challenges for the state is the July 2011 disbandment of the Public Health Pest Management section due to state budget cuts, Richards added. Formed by the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources in the 1970s, the organization provided much needed assistance to counties in their mosquito abatement programs.

“The battle against mosquito-borne diseases requires a number of strategies, said Richards. “This includes a full range of public health education, research, pesticides and vaccines in order to combat the problem.”

While Richards’ research is just one element of solving the mosquito problem, her work “will significantly impact the health of the public we serve,” said Dr. Don Chaney, chair of the Department of Health Education and Promotion, housed in the College of Health and Human Performance.

Richards is an ECU graduate, who earned a bachelor’s in biology in 1998 and a master’s in environmental health in 2001. She graduated from N.C. State University in 2005 with a Ph.D. in entomology.

Her interest in the research is driven by the need to improve public health. “It’s not that I like bugs,” she said. “These vectors can cause serious illness and even death to humans. The public health aspect of my work is where my real interest lies.”