ECU research focuses on community gardens, farmers markets

New ECU public health graduates Ashley Ronay, left, and Leah Mayo, right, worked on projects related to fresh fruits and vegetables in eastern North Carolina (Photos by Cliff Hollis).

Summer’s longer days and warmer temperatures offer more opportunities to eat fresh fruits and vegetables but not everyone knows how or where to get healthy foods.

Recent graduates of East Carolina University’s masters of public health program spent the fall and spring semesters on two projects related to fresh fruits and vegetables. One project examined kids’ experiences in a community garden, and the other looked at factors like zoning and how it can impact access to fresh foods in rural eastern North Carolina.

ECU alumna Ashley Ronay worked with students enrolled in the Pitt County Community Schools and Recreation afterschool program at Wintergreen elementary and intermediate schools through a participatory research project called Photovoice, a method where children took pictures of what the community garden meant to them.

Learning in the field

Samuel Hardy, whose wife owns a stand at the Pitt County Farmer’s Market, selects ripe tomatoes for the ECU researchers to take home.

The children, ages 8 to 11, volunteered in the Making Pitt Fit Community Garden on County Home Road and tended plots when people were out of town. Some had never been in a garden. “Some indicated that they had never tried a strawberry or blueberry,” Ronay said.

The children were asked to take 10 pictures and to pick two photos to discuss during a group meeting. “It was hard for them to choose because they wanted to talk about all of their pictures,” Ronay said.

Five main themes developed as Ronay and her faculty adviser, Dr. Stephanie Jilcott Pitts, assistant professor of public health in the Brody School of Medicine, analyzed the data:

- The children tried new foods, and ate more fruits and vegetables.

- The children recognized some of the foods, like chili peppers, as ingredients used to cook food at home.

- Some learned how to garden because it was their first time caring for plants.

- They developed an appreciation for nature and learning how and where plants are grown.

- They liked helping others and having fun in the garden.

Pitt County Community Schools and Recreation’s Alice Keene, special projects coordinator, and Courtney Riggs, after-school coordinator, were important partners, Ronay said. The research could lead to similar projects in the future.

Keene said the project would not have been possible without Ronay and ECU.

“It is still amazing to me all that they learn, from planting to pollination, to ‘good bugs to bad bugs,’ to watering, harvesting and enjoying the wonderful foods,” Keene said. “While all this is happening, they are also getting critically-needed physical activity. Many of them have brought their families to the garden and some parents have even started a small garden at home because their children insisted on it.”

Enhancing access to healthy foods

In a separate study, recent ECU graduate Leah Mayo examined the associations between farmer’s markets, zoning and land-use policies in rural northeastern North Carolina.

“The built environment is thought to have an influence on one’s health,” Mayo said.

Between November and March, Mayo gathered data on 13 northeastern counties: Bertie, Camden, Chowan, Currituck, Dare, Edgecombe, Gates, Hertford, Martin, Northampton, Pasquotank, Perquimans and Washington. Hyde and Tyrrell didn’t have available zoning so they couldn’t be included in the study.

Children who worked in the gardening project learned to try new, healthy foods.

The counties are some of North Carolina’s most economically-distressed and least healthy with 20.5 percent living in poverty and 33 percent classified as overweight or obese.

“Access to healthy foods is one way to combat obesity,” said Mayo, adding that studies have shown low-income and minority neighborhoods have less access to healthy food outlets. One study from California showed a higher concentration of fast food restaurants located in minority and low-income areas than healthy food outlets.

Even in rural areas that have fruit and vegetable or roadside stands, residents may not know about them or have difficulty getting to those outlets, Mayo said.

Examining effects of zoning

Mayo worked with county managers and planners to access land use data, and gave each county a ‘healthy food zoning’ score based on their zoning regulations and examined the association of this score with the numbers of fruit and vegetable outlets.

The study revealed that many zoning ordinances don’t include healthy food outlet-related language or may not specifically mention places like roadside or produce stands or farmer’s markets. She also looked to see if the zoning permitted healthy food outlets in different zoning districts.

“Increasing healthy food outlet language and increasing permitted uses of these outlets would make it easier to open such an outlet in places of need within a community,” Mayo said.

If a place is not mentioned in the zoning or is not permitted in a certain district, an application and approval process would be required. This could be difficult for someone working in the agricultural industry due to the demands of the work, Mayo said.

Overall, Mayo found planners were receptive to adding the language to the ordinances.

Ultimately, a change in policy could improve access to healthy foods in rural areas, eliminating food deserts, “to make healthy living an easy choice,” said Mayo, who is based in Edenton and serves the 15 counties as the Region 9 Community Transformation Grant active living coordinator for Albemarle Regional Health Services.

“With these two projects, Ashley and Leah did a great job of engaging the community to evaluate real-world solutions to the major public health problem of obesity,” said Pitts, who advised both students on their projects.

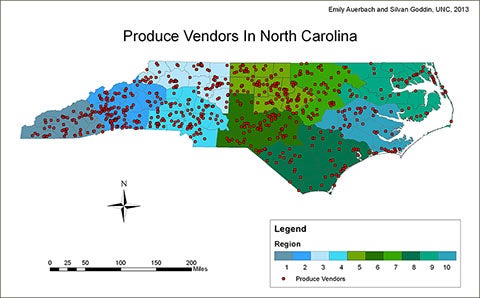

Identified on a North Carolina state map are vendors that sell healthy produce. Click on the image for a larger view.