DIFFICULT DECISIONS

Research examines guest workers' motives, struggles

East Carolina University professor of anthropology David Griffith has taken his research abroad to study managed migration, the value of labor and its effects in Mexico, Guatemala, Canada and the United States.

Griffith and Ricardo Contreras, an anthropologist and an adjunct research professor at ECU, were awarded $185,000 in funding by the National Science Foundation to conduct ethnographic research on guest workers and their families who came to the United States and Canada from Chimaltenango and Santa Rosa in Guatemala, and Sinaloa and Michoacán in Mexico.

Specifically, they studied women who came to eastern North Carolina and Virginia and worked in the crab-picking industry for eight months at a time. They have followed several of the same women over the past four years and have met them both in the U.S. as well as at their homes in Guatemala and Mexico.

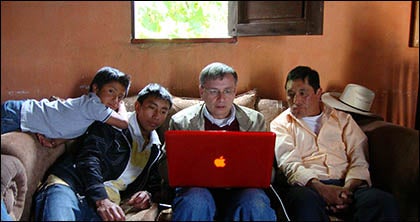

Dr. Ricardo Contreras, holding his laptop computer, and members of a local family examine photographs and maps while Contreras was in Chimaltenango, Guatemala researching managed migration.

“Some of these women (work in the U.S. for eight months at a time) for up to 20 years,” Griffith said. “You wonder what makes a woman do something so drastic.” The main reason, Griffith explained, is money, lack of opportunity in their homelands and abusive relationships.

“Economics are the basis of (the migration), but it is much more complex,” said Contreras. “We interviewed one woman who said she would have died if she didn’t come (to the U.S.).”

Contreras said the decision to migrate left many of the women conflicted. “They know they need to do this but they are hurting for themselves and their kids,” he said.

While it may be difficult for the women, Griffith and Contreras said that the work they do abroad helps their local economies back home. The labor workers bring money back to Guatemala and Mexico and use it for various reasons, such as fixing their homes, which employs local workers. Or they may use the money they have earned to send their kids to college.

“It’s a chain of effects,” said Griffith.

Griffith and Contreras traveled abroad a few times a year and stayed for a couple weeks at a time. Griffith said that while it may be more convenient to meet the workers in the U.S., it is “different” meeting them in their homelands.

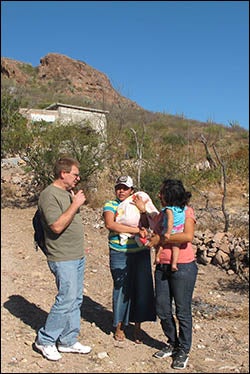

Dr. David Griffith speaks with women in Sinaloa, Mexico, about their work and experiences when they migrated temporarily to Virginia.

“When they are here (in the U.S.), they come to work and stay busy. They don’t like idleness because they start to think about being away from home,” said Griffith. “But when we talk to them at home we get to see them in a different light. We are able to better understand their struggle.”

Contreras said the workers are often willing to work up to 20-hour days, making them valuable employees to large industries such as the crab picking industry.

“They absolutely need these workers; they are a blessing,” Griffith said. “It is convenient for employers and often the community doesn’t even know about them.”

Contreras and Griffith started following guest workers in 2009.

“I’ve been interested in immigration and guest workers for a long time,” said Griffith. “I did my dissertation on Jamaicans who cut sugar plants.”

Griffith and Contreras said their study is important considering the talk of immigration reform currently taking place.

“There are a lot of benefits from the guest worker program, but we’d like to improve it,” said Contreras. “The study can produce data leading to finding a solution for the controversy of undocumented immigration.”

Griffith and Contreras plan to continue to work with guest workers and said their research has affected their work in the classroom as well.

“I tell students about the realities that are completely unknown,” said Griffith. “I make an effort to have them realize these people and make people who are invisible visible.”

Griffith has written a book titled “Mismanaging Migration: Guest Workers in America,” that is soon to be released.

In Chimaltenango, Guatemala, a local Kaqchiquel woman concentrates on her weaving surrounded by ears of corn left out to dry.