CONNECTING PAST & PRESENT

ECU’s Country Doctor Museum reopens, showcases rural health care during past pandemics

Living through a pandemic isn’t just the stuff of history books anymore. Now, visitors to the country’s oldest museum dedicated to rural health care can connect on a more personal level with health care from the past.

The Country Doctor Museum, re-opened in May, featuring artifacts and exhibits that show visitors the way health care in the East evolved over time.

Before closing because of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, the museum experienced a steady flow of visitors. While it was closed to visitors, staff took inventory of artifacts and exhibits to ensure the museum’s offerings would be better than ever once it could reopen.

“Our staff completed a comprehensive inventory and ranking project for the each for the 4,700 objects in the museum collections,” said Annie Anderson, the museum’s director. “We’d take turns stopping by the museum to check on our facilities and pick up artifact boxes to take home. We took advantage of our time without visitors to thoroughly clean the exhibit areas and prepare for guests to return. A bright spot throughout the pandemic was our work with students, either remotely or in-person.”

View this video on YouTube for closed-captioning.

Country Doctor Museum staff presented virtual programming to middle-school students, conducted a virtual tour and Q&A session with ECU students and trained interns to help with collections management and installing museum displays in the halls of the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University.

The museum was able to reopen briefly from September until COVID-19 case counts began to rise again in November. It reopened officially in May.

Now that business has returned to normal, staff and visitors take advantage of bringing the past to life through tours and education sessions.

PANDEMICS: THEN AND NOW

PANDEMICS: THEN AND NOW

ECU’s Country Doctor Museum helps visitors draw similarities between the COVID-19 pandemic and pandemics from more than a century ago, including the 1918 influenza pandemic.

Country Doctor Museum Director Annie Anderson explains:

“The beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic shared similar traits to the 1918 influenza pandemic: Some geographical areas were spared at first, we lacked a good understanding of how to treat patients with the virus and there were questions about how to best prevent exposure. In 1918, people had few therapeutics that could help offset symptoms and they learned to wear masks and limit travel. Then, as now, communities came together to help one another. Groups throughout eastern North Carolina organized volunteers to bring food and supplies to families and communities hard hit by the influenza virus.

Our Sick Room exhibit features a timeline of vaccine milestones illustrating when specific vaccines were discovered; many took years of research. Our guests are surprised to see that many of the vaccines we take for granted today were only recently developed in the latter part of the 20th century. For example, although research for a polio vaccine began in the 1920s, Dr. Salk’s vaccine first became available in the 1950s. One guest to the museum remarked that she thought vaccines were the most important medical discovery to impact health during her lifetime. I am greatly impressed that our country developed three successful COVID-19 vaccines within a year. These vaccines clearly have an impact on the transmission of COVID-19 and have helped reduce suffering and death.

A visit to the Country Doctor Museum provides a great perspective on the changes in rural health care. Our guests are exposed to many of the challenges faced by country doctors at the turn of the 20th century, and how some of these challenges still exist in small rural communities today.

Most importantly, I hope touring the museum will illuminate the importance of the patient and doctor/health care provider relationship. Sometimes people don’t recognize the significance of this connection until they find themselves in a health crisis (or in the middle of a global pandemic!) The health care provider becomes their medical expert, a guide, and an educator. I believe this was the role of the country doctor and these are the characteristics I look for with my own practitioners.”

Some of the museum’s displays offer a view of life during past pandemics and disease outbreaks.

“The museum’s ‘Sick Room: Home Comfort & Bedside Necessities’ exhibit speaks to the care of ill family members, and some of it is applicable, whether it was in the early 20th century or today,” Anderson said. “During the tour, we discuss with our guests how people washed their hands more frequently or covered their cough as they learned how illness was spread. It seems we became more fully acquainted with these types of preventative measures during the past year.”

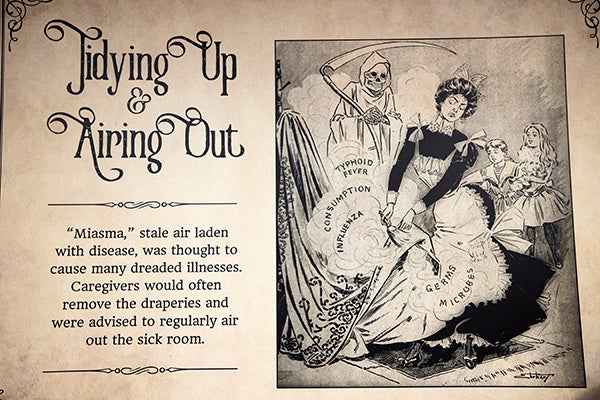

Anderson added that images housed in the museum draw connections between ways people tried to prevent disease over the years, even as knowledge and capabilities have evolved.

Museum is showcasing “The Sick Room: Home Comfort & Bedside Necessities,” an exhibit that speaks to the care of ill family members, and prevention of spread.

“We also have a great image in the sick room of trying to keep the germs of various illnesses out of the home,” Anderson said. “It reminds me of how families were wiping down groceries and other cleaning hacks to prevent COVID-19 from entering their homes. I think the care and concern families have for their sick loved ones remains constant through time, although the technology to care for them changes.”

The museum’s Polio display and the iron lung at the museum also highlights the spread of illness.

“We’ve learned from our guests about how different communities reacted to the threat of polio epidemics during the early and mid-20th century,” Anderson said. “Some would close theaters or swimming spots, wherever children and teenagers liked to congregate to reduce the spread of polio. Other families would roll up their car windows as they drove through a town known to have a recent outbreak of polio. Like COVID-19, many polio cases were mild, but a small percentage could seriously threaten one’s health and well-being. I remember one guest shared a memory of his mother falling to her knees in gratitude when she heard on the radio that a polio vaccine was just discovered.”

Layne Carpenter, archivist for Laupus Library’s history collections, said the precautions taken in different eras highlight the similarities between how people work to avoid disease.

“During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, the North Carolina State Board of Health encouraged local health departments to close public spaces and enact quarantines,” Carpenter said. “Mask wearing was common as well, though at the time most masks were made from several layers of gauze. Local health departments also encouraged people to frequently clean the sick room, although their methods often involved airing out the space and using other cleaning techniques that we would question today.”

Laupus Library Director Beth Ketterman said that Carpenter and the Country Doctor Museum team continue to be outstanding partners in the mission to collect and interpret the history of rural healthcare in eastern North Carolina.

“We are certainly living our history right now, so the archival materials that the library’s history collection is able to provide the Country Doctor Museum, combined with the artifacts and expertise in Bailey, allow us to connect past understanding of pandemics and infectious disease with our current COVID-era experiences,” said Ketterman.

Bringing those stories to life for visitors is once again at the forefront of the staff’s efforts.

“We love having guests visit the museum,” Anderson said. “They can expect a guided tour, just as we offered prior to the pandemic and our medicinal herb garden is included on the tour.”

Outside the museum, the acclaimed herb garden is once again growing under the care of staff.

“We were fortunate to be able to replant this spring and a good number of our herbs are currently in bloom, such as our foxglove, feverfew, milkweed, and echinacea,” Anderson said.

In the past, the museum has had a strong presence on ECU’s campus. That tradition will continue in the coming weeks as well.

“An expanded history of nursing exhibit will be on view when the Laupus Library reopens to the public in the next few weeks,” Anderson said. “Our exhibit space within the museum’s historic buildings is limited so we like to share our collection with the ECU community in Greenville. We have a new exhibit in the corridor between the Brody School of Medicine and Vidant, and a new exhibit will be installed next week on the second floor of ECU’s Family Medicine Center.”

Now that the museum is once again open, Anderson hopes visitors will continue to nurture an appreciation for rural health care and its advances over the years.

“Our guests leave with a better understanding of the progress of health care including medicine, medical education, nursing and transportation,” she said. “I hope they also have a greater appreciation of the challenges involved with rural health care.”

Under ECU’s safety guidelines, masks are required inside the museum and hand-sanitizer stations are positioned in each building. Tour groups are kept on different paths and guests are encouraged to reserve a tour time in advance by contacting the museum through email, by phone or on Facebook.

For more museum information including operating hours and tour reservations, call 252-235-4165 or visit www.countrydoctormuseum.org.