HEALING MENTAL WOUNDS

ECU trains counselors to work with veterans, service members, families

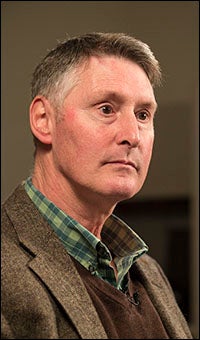

ECU professor Dr. Mark Stebnicki, left, prepares to conduct an interview with military veteran Ty Shaw, right, for use in the new ECU distance education course in military and trauma counseling. (Photos by Cliff Hollis)

The six-inch scar on Ty Shaw’s left leg is a lasting reminder of a mortar blast he suffered while on patrol in Iraq.

Shaw’s rehabilitation was long. He jogged for the first time three years after his injury. Now he is a civilian military police officer at Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune.

Helping service members, families and veterans like Shaw cope with the physical and mental injuries of war is the focus of a new distance education rehabilitation counseling course at East Carolina University.

Ty Shaw

Nineteen graduate students are enrolled this semester in the first offering of military and trauma counseling taught by Dr. Mark Stebnicki, professor of addictions and rehabilitation studies in the College of Allied Health Sciences. Dr. Lloyd Goodwin, professor in the department, proposed the course two years ago based on the emerging population and need, Stebnicki said.

Stebnicki is using 30-minute interviews with veterans like Shaw, families of current military members, a flight surgeon and others to share personal stories and teach students about the tradition, terminology and culture of the armed forces. ECU’s Multimedia Technology Services records the interviews. Videotaped lectures, presentations, articles, readings and blog posts supplement the case studies. Topics vary from transitioning from active duty to civilian life to the impact of war on families.

The course was developed for the recently approved Military and Trauma Counseling Certificate Program to start this fall. It will be an online program for professional counselors focused on the military’s unique medical, psychosocial, vocational and mental health needs and traumatic experiences, Stebnicki said.

The course incorporates training in civilian disaster and crisis response ranging from floods, hurricanes, or tornadoes to plant explosions, workplace and school violence or bank robberies.

“We tend to think of first responders as paramedics, firefighters and emergency medical technicians, but from the mental health side, we do the mental health response,” Stebnicki said.

The course is culturally sensitive to soldiers, sailors, Marines, airmen and women, Coast Guard and National Guard members and reservists. Calling everyone in the military a “soldier” isn’t accurate, and can be offensive to some branches, Stebnicki said.

While service members prepare for combat and the possibility of injury or death, “seeing someone get blown up in front of you has a terrific psychological cost to it,” Stebnicki said. “Everybody heals at their own rate and all don’t respond to one treatment method.”

Early diagnosis and treatment of PTSD along with other conditions like depression, substance abuse and anxiety disorder is important because untreated PTSD can progress to more severe, chronic mental health conditions, Stebnicki said.

“At this time in history, we have more suicide completions among service members than ever before,” Stebnicki said. “It puts a finger on why we need mental health services. We can’t ignore it.”

Mark Stebnicki

Shaw returned to the United States after his injury in March 2003. He didn’t realize he had PTSD at first. “I had an injury to deal with, but then, I found myself getting more angry,” said Shaw, who worked with counselors from Veterans Affairs and Veterans of Foreign Wars along with physical and occupational therapists.

The stigma that has come with mental health treatment – that service members shouldn’t show vulnerability or risk repercussions – may still exist but is less pronounced, Stebnicki said. “There are more mental health services on base now than any war ever because we’re starting to see the impact of PTSD,” he said.

In Iraq, Shaw supported infantry units trained in anti-mine warfare and provided support in explosives, engineering and other areas. He often wore protective clothing, and carried a gas mask at all times. All the things he did, from pushing abandoned cars out of the way so Humvees could maneuver, to keeping civilians at a safe distance, or guarding against the constant threat of snipers, caused anxiety. “You’re running on adrenaline. It’s draining in and of itself, and when you try to sleep, you don’t get a lot of sleep,” Shaw said. “It’s stressful.”

Shaw, originally from Longview, Wash., received a Purple Heart for his service as a combat engineer with the U.S. Marines from August 2001 until June 2004.

It’s been 10 years since his injury; he was one of the first hurt in the invasion of Iraq.

“You have to have the mindset you want to get better,” Shaw said. “You have to have the will and want to.”

To learn more about the course, contact Stebnicki in the Department of Addictions and Rehabilitation Studies at 252-744-6295 or stebnickim@ecu.edu.