EXPLORING PFAS

7 questions with PFAS expert Dr. Jamie DeWitt

A professor at East Carolina University was recently selected to join the National Academies’ Standing Committee on Use of Emerging Science for Environmental Health Decisions (ESEHD).

Dr. Jamie DeWitt of the Brody School of Medicine’s Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology joins the committee of 16 environmental science and policy experts charged with convening several workshops each year to explore how new scientific advances, technologies and research methodologies could deepen our understanding of the effects of environment on human health.

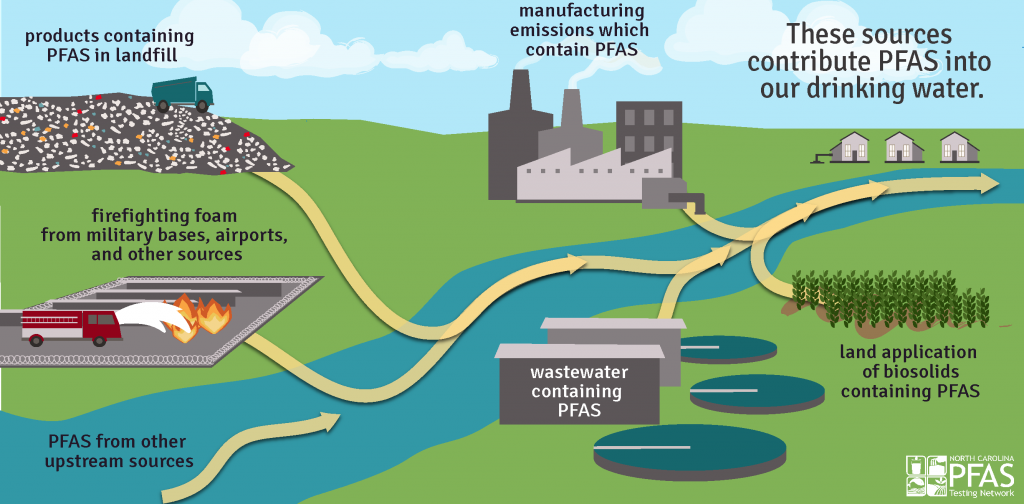

Sources of PFAS in drinking water. (Contributed by North Carolina PFAS Testing Network)

TESTIFYING ON PFAS

Dr. Dewitt testified in front of a U.S. House of Representatives Appropriations Subcommittee Hearing on Remediation and Impact of PFAS from the Subcommittee on Military Construction, Veterans Affairs and related agencies on March 24. She was on a panel of experts including Erin Brockovich. This was the third time she has testified in front of Congress about the dangers of PFAS in the last three years.

Her testimony begins at 1:24:38. Visit YouTube for closed captioning.

DeWitt has been studying the immunotoxicity of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) since 2005. Her work explores how emerging environmental contaminants can alter immune function and how early life or adult exposure to environmental contaminants may impact the immune and nervous systems and how contaminants may disrupt how these systems communicate with one another. She is especially interested in the application and communication of scientific data to the environmental health decision making process.

According to the N.C. PFAS Testing (PFAST) Network, PFAS are human-made chemicals – such as PFOA, PFOS and GenX – that have been manufactured and used in a variety of industries since the 1940s. These chemical compounds are commonly found in commercial household products, industrial facilities, drinking water and food grown in PFAS-contaminated soil or processed with equipment that used PFAS.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry points to research indicating that certain PFAS may affect the growth and development of infants and children, interfere with the body’s natural hormones, affect the immune system and increase the risk of cancer.

In addition to her work with the N.C. PFAST Network, DeWitt was one of three national experts named to the Michigan PFAS Action Response Team’s Science Advisory Workgroup, which will help Michigan officials set an enforceable drinking water standard for PFAS. She is also part of an EPA-funded research effort – led by a team from Oregon State University – that is investigating the effects PFAS compounds have on humans.

DeWitt also testified before Congress in 2019 about the negative health effects of chemical compounds that are estimated to be in the drinking water systems of 19 million Americans.

According to Dr. Sharon Paynter, Assistant Vice Chancellor for Economic and Community Engagement, DeWitt also works with educators, organizations and the public to spread awareness about PFAS.

“DeWitt has worked regionally with community partners Cape Fear Public Utility Authority (Wilmington) and Sound Rivers (New Bern) as part of her Engagement and Outreach Scholars Academy project,” said Paynter. “The project aimed to educate the public about what PFAS are, where they come from, how people are exposed, and what they do once they’re in our bodies.”

View this video on YouTube for closed captioning.

DeWitt answers seven questions to provide the latest updates about what the scientific community has learned and how consumers can limit their exposure to PFAS.

1. What is your role on the Use of Emerging Science Standing Committee and your reaction to being chosen to serve?

As a member of the Standing Committee, I will work with other Committee members and NAS staff who work with the committee to organize workshops on the use of new science, tools and research that inform environmental health decisions. I also will need to stay up to date on emerging science used in environmental health. I was absolutely honored as well as surprised. I was a participant in a workshop organized by the committee and received the invitation from NAS staff shortly after.

2. Why is it significant to have someone representing eastern North Carolina on that committee?

This committee has a very close relationship with the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). This is an acknowledgement of the quality of scientists and scientific research in the environmental health sciences at ECU.

3. What are the most recent developments in regulating PFAS in North Carolina and beyond?

Several states in the U.S. have passed “Maximum Contaminant Levels” for PFAS in drinking water. These are legally enforceable standards limiting the amount of PFAS covered by the MCL in those states. The European Union has also embraced the “essential use concept” in their approach to managing PFAS by asking for what uses are PFAS necessary for the health, safety or is critical for the functioning of society. I think that this is a very proactive approach.

4. We recently learned about a recent discovery of PFAS in Jacksonville, N.C. Are you aware of any other significant PFAS discoveries within the past year? Do you anticipate more and way?

No discovery of PFAS in the environment is a surprise to me anymore. They really are everywhere scientists look. They’re in the Arctic, the deep ocean, blood from umbilical cords. They’re in dental floss, contact lenses, cell phones, food packaging, carbonated water and the list goes on. They’ve been around for less than a century and have been spread across the planet.

5. How can people feel safe if the drinking water in their home is contaminated and many of the products they purchase contain PFAS?

First, people do have options for avoiding PFAS by researching products to find out about PFAS use in those products (Green Science Policy Institute and Environmental Working Group have good information for consumers) and deciding whether or not to purchase those products. Second, PFAS can be filtered out of water, but not all filters are fully effective. If someone is going to invest in a filter, make sure it is a type that is effective.

6. You recently were featured with other environmental leaders about the potential impact PFAS could have on the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine. Can you tell us more about that?

One of the health effects of some of the well-studied PFAS is “immunotoxicity” or the negative effects on the immune system. One of the functions of the immune system that we know can be affected by PFAS exposure is the response to vaccines. An agent, like PFAS, that reduces your body’s ability to make antibodies against a vaccine means that some people who are exposed to PFAS might not make a strong response when they get their COVID-19 vaccine. Scientists are still studying this relationship. I think that if you live in an area where PFAS are a concern, be extra careful about following guidelines for avoiding COVID-19 – wear a mask, wash your hands frequently, and maintain social distance. Even if your vaccine isn’t as effective as it could be, getting one still gives the immune system a boost and will help your body to protect itself if it is exposed to COVID-19.

7. We’ve learned that some PFAS research groups are partnering with COVID-19 researchers to learn more about the spread of both PFAS and COVID-19. Is it common for the study of PFAS to cross into other fields of study? If not, why not and why is it happening in this case? If yes, what does that say about the importance of studying and regulating PFAS?

This type of “transdisciplinary research” is very common in the toxicological sciences and does occur for other types of diseases as well. For example, one of my colleagues who studies reproductive health is working with me to see if PFAS can affect the reproductive system. Another colleague who studies the immune system in the lungs works with researchers who study various types of air pollutants and lung diseases.