COVID-19 AND THE HOLIDAYS

10 tips for surviving the holiday season, difficult conversations during COVID-19

As the holidays approach, COVID-19 infection rates continue to spike and political anxiety simmers following a contentious election. Consequently, families around the globe are being forced to make difficult decisions to keep themselves and their loved ones safe, while also trying to navigate the potentially difficult conversations they might encounter.

East Carolina University faculty experts in virology, psychology and misinformation provided these tips on how to plan for the holidays and keep conversations with family pleasant and productive.

Listen to the podcast:

CELEBRATING SAFELY

Dr. Rachel Roper, right, associate professor in the Brody School of Medicine’s Department of Microbiology and Immunology, discusses celebrating the holidays safely.

(Photos by Rhett Butler)

1. Keep your gathering as small as possible.

Gatherings in North Carolina are currently limited to 10 people indoors, but health experts suggest limiting your holiday gatherings to as few people as possible in order to reduce potential exposure to the virus.

“Anytime you’re around people that you do not live with, you could be exposed to the virus. The more people you’re around, the more likely you are to be exposed to someone who is shedding virus,” said Dr. Rachel Roper, an associate professor in the Brody School of Medicine’s Department of Microbiology and Immunology who oversaw vaccine trials for the original SARS coronavirus in the early 2000s and is now working on COVID-19 diagnostics and developing a vaccine for the novel coronavirus. “You have to think about your own risk factors and other people’s risk factors and make the decision yourself.”

Roper added that if you are interacting with anyone not living in the same house as you, wearing a mask during those interactions is crucial. If you’re able, consider gathering outside instead.

“Wearing masks is important, especially if you’re inside because the virus transmits so much more easily inside than outside,” Roper said. “If you can be outside it’s better than inside. If you can be with fewer people, it’s better. It’s safest if you’re with people that you already live with who you’re exposed to on a daily basis.”

2. Reduce the risks — practice the 3 Ws and sanitize high-touch surfaces.

Because many who have COVID-19 do not have symptoms and may not know that they are infected, it’s important to take steps to reduce the potential spread of the virus. In addition to practicing the 3 Ws — waiting six feet apart, wearing a mask and washing your hands — it’s important to regularly sanitize surfaces that multiple people touch.

“You can reduce your risk by keeping distance, wearing a mask — especially indoors, washing your hands and sanitizing anything that is touched by multiple people,” Roper said. “Avoid touching your face unless you have just washed or sanitized your hands.”

Roper suggesting taking extra care to sanitize items in the house that are frequently touched by others such as:

- Door knobs

- Toilet handles

- Faucets

- Refrigerator door handles

Roper also suggested that instead of using shared serving utensils, each person should use their own flatware (before eating with them) to serve themselves.

3. Understand that taking your temperature and getting tested can provide indicators that you are infected, but they can’t rule out that you’re not infected.

“Checking your temperature is a good idea. I would do it morning and night,” Roper said. “Especially before you go anywhere to meet anybody, make sure your temperature’s OK.”

Roper added that the absence of a fever does not necessarily mean someone is not infected.

“A lot of people don’t even get a fever (when they’re infected),” Roper said. “Just because your temperature’s OK doesn’t mean you don’t need to wear a mask.”

Similarly, because COVID-19 is thought to have an incubation period of up to 14 days, according to the CDC, individuals can harbor and potentially spread the virus before exhibiting symptoms or testing positive.

“The problem with that is that tests aren’t perfectly sensitive, and if you test negative one day, that just means that you’re negative that day. You could be positive the next day,” Roper said. “So, we could all get tested before we travel or after travel, but if you’re not getting tested every day, you don’t really know. If you get exposed one day, you could test positive two weeks later. You could be incubating the virus and negative and then one day you turn positive. So, testing is helpful, but it does not perfectly protect everyone.”

Dr. Marissa Carraway provides insight on how to navigate difficult conversations during the holidays for the Talk Like a Pirate Podcast on Nov. 9 in ECU’s Brody School of Medicine Auditorium.

4. Plan ahead and share your plan with others beforehand.

“For each individual, we have to decide what we’re comfortable with and what our boundary is going to be,” said Dr. Marissa Carraway, a clinical psychologist and clinical assistant professor in the Brody School of Medicine’s Department of Family Medicine. “We will probably cope a lot better with the stress in these situations if we communicate those boundaries with our family and friends beforehand.

“If that means you’re willing to go to a family function if everyone is agrees to wear a mask, communicate that in advance with your family so that people aren’t caught off-guard by differences in expectations and comfort levels in the moment, which can cause a lot of tension.”

Carraway emphasized being clear and firm when sharing your plans and boundaries with others, while trying to understand of others’ perspectives, and acknowledge the possible discomfort of knowing that others might not be supportive of your decisions.

“We don’t have to defend our stance, we just have to say clearly: ‘This is what I’m comfortable with,’” Carraway said. “Acknowledge other people’s feelings: ‘It’s disappointing; I’m disappointed too that we can’t have our traditional family gathering in the same way that we normally would.’”

NAVIGATING DIFFICULT CONVERSATIONS

5. Choose Your Battles

When it comes to tense conversations about divisive issues, like politics or COVID-19, Carraway suggests deciding what your goals or intentions are for the interaction and making sure that they’re reasonable.

“If your goal is to change people’s minds or make them agree with you, I don’t know that that’s very feasible,” Carraway said.

Particularly if you’re interacting with someone with very different beliefs, exercise discretion in the conversations in which you participate, and frame your perspective in ways that are approachable.

“I do think there’s a way that you can have these conversations,” Carraway said. “I think you have to pick and choose. If you find yourself a polar opposite from someone in all the ways, you’re certainly not going to tackle all those things in one conversation.”

Carraway added that if it’s a topic that might be more distressing for you to keep quiet about than it would to participate in a potentially uncomfortable conversation, speak up, but frame your perspective in ways that are approachable.

“If there’s something you feel particularly passionate about — especially if there’s data to back it up — that might be the thing that you say, ‘Well, actually, here’s what I heard’ in a very approachable way. If you approach it like, ‘Can I share with you some data that I read?’, asking permission to share your perspective will probably go over better than if you say, ‘Well, actually that’s wrong. Here’s what’s right.’”

6. Know the data.

If you anticipate difficult conversations about COVID-19, politics or misinformation, providing data from reputable sources can be helpful to a conversation.

“I’m always into the data: How many people are getting infected, how many people are dying,” said Roper about COVID-19, adding that she recommends finding information about the pandemic from Johns Hopkins’ COVID website or WorldoMeter. “Some people don’t realize that there were 126,000 new cases a day recently. …It’s really important to understand that this virus is out there, it is circulating, and it is dangerous.”

Carraway agreed that providing data can be helpful in preventing an ongoing debate about the topic.

“I think data is important and I like the idea of using the data because I think maybe one of the best things that we could do is to avoid getting into a debate about COVID-19,” Carraway said. “I don’t think that anything fruitful will come of that other than maybe increased family tension during the holidays, which is not what we’re probably striving for. So relying on the data is great because it’s harder to refute that.”

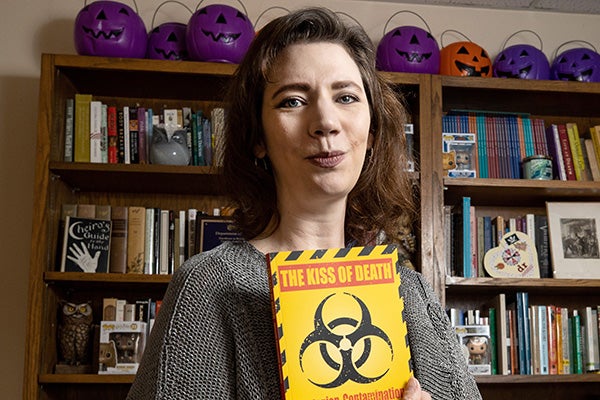

Dr. Andrea Kitta, associate professor of English, won the 2020 Brian McConnell Book Award for her book, “The Kiss of Death: Contagion, Contamination and Folklore,” which sheds light on how information and misinformation spread in an outbreak like COVID-19.

7. Pay attention to sources.

Dr. Andrea Kitta, a folklorist with a specialty in medicine, belief and the supernatural and associate professor in the English Department in ECU’s Thomas Harriot College of Arts and Sciences said that tracking down sources is crucial to reducing the spread of misinformation.

“We all have to think about our sources and look at the information we get. That can be hard to do, especially when you’re short on time. We don’t want to look at sources or multiple sources. We just want to get our information easily,” said Kitta, who recently published a new book, ‘The Kiss of Death: Contagion, Contamination, and Folklore.’ “We have to track those down. … Especially when I see a medical study mentioned, I try to find that medical study and I try to read it or at least look through the summary and see what other people have said about it. … How many people were in the study? What journal was it in? Was it a peer-reviewed journal? There’s a lot of little things that we can do to check those things out a little further. …That’s something we have to make time for.”

Kitta added that it’s important to understand that misinformation doesn’t always occur deliberately or for nefarious reasons. Sometimes it occurs as a result of people making mistakes or information changing. For example, because the virus that causes COVID-19 is a novel virus, we know more about it now than we did earlier this year.

“Just because we see something that contradicts something we saw previously, it doesn’t necessarily mean that one or the other was wrong,” Kitta said. “It has to do with the information we had at the time.”

8. Stop, collaborate and listen.

Experts recommended practicing empathy, asking questions, listening and finding common ground to help diffuse tense conversations.

“What we need to do is try to understand people’s perspectives,” Kitta said. “Even if we don’t agree with them, that’s how we help have a discussion. Ask somebody, ‘What do you think is the big problem with it?’ Start with what they think instead of assuming what they think. … Sometimes we need to listen a little bit more, but sometimes we need to listen so that we can help correct as well.”

To diffuse tense conversations, it can be helpful to focus instead on areas where you can find common ground.

“I would say there are probably parts of the pandemic experience that we can all agree upon or relate to — like the fact that it stinks,” Carraway said. “Often if there’s a topic that we have differences of opinion, there’s some common ground that we can connect on and then leave it alone after that.”

MAKING IT MERRY

9. Get creative: Modify traditions, start new ones.

To safely celebrate the holidays while still making the season merry and bright, plan to modify traditions to make them safer, and make new traditions with loved ones.

“Anecdotally, we are seeing so much more stress and depression and isolation. … People have pandemic fatigue — they’re tired of the quarantine, of avoiding friends and family and I think that’s understandable, but I think it makes a lot of people nervous at the same time,” Carraway said. “People are starting to get a little bit lax, because I think they’re feeling the push and pull of that — I want to stay safe, but I need that human connection. So, I think our biggest challenge with this holiday season is going to be to get creative, find ways to modify our family traditions, start new family traditions to find that connection with our loved ones, but to do it in a safe way.”

10. Expect and accept that this holiday season will be different.

“Change is uncomfortable and hard, and we don’t always like it,” Carraway said. “But I think we have to expect and accept that this holiday season is going to be different. If it’s not different it won’t be safe. We have to make some compromises and be willing to accept that it may not be what it has been in the past. But I think that the hope is that it’s temporary… It doesn’t mean that we can’t ever have the holiday season like we used to, but for this year it will be a little bit different. If we go into it knowing that, accepting that, maybe we can still find some connection and meaning and holiday spirit.”