Agromedicine Institute continues aid, outreach through western North Carolina’s hurricane recovery

Mental health, supplies and safety equipment lead priorities for 26-year-old statewide health collaboration.

Recovering from a natural disaster can be as harrowing as the event itself, and it does not discriminate, but it lands differently for farmers and farm families. Growers are tied to the land operationally, financially and emotionally. For this reason, government agencies, nonprofits and partnerships have keyed in on farms, and one such group aiding Helene recovery is the North Carolina Agromedicine Institute.

Amy Nance Nelson is a registered nurse with the North Carolina Agromedicine Institute. She and her husband operate a small farm in Watauga County.

“Farmers can’t sit around until they feel like responding to the damage at their place,” said Amy Nance Nelson, a registered nurse with the institute for the last three years. “In the case of Hurricane Helene, [farmers] worked during the storm, heading off problems. If they have animals, those animals have to be tended, rescued, sheltered, aided. They have to eat.”

Founded in 1999, the institute is a collaboration between East Carolina University, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University and North Carolina State University to address unique health and safety risks to farmers, farm workers, foresters, fishermen — and the families dependent upon them — in all 100 North Carolina counties and tribal lands, meeting them where they are for health screenings, education and safety interventions. During Helene recovery, the institute coordinated and delivered personal protective equipment and chain saw safety education, and used networks to address farmers’ mental health needs, among others.

Nelson and her husband operate a small farm in Watauga County where they grow pastured meats, organic vegetables, free-range broilers, eggs and more. Unlike many of their close neighbors, they suffered no major loss — barn doors ripped off, a high tunnel destroyed and sustained flooding, but no structural damage. The couple spent much of their time coordinating and transporting needed supplies including through Nelson’s institute job.

Former North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper described Helene as “the deadliest and most devastating storm in North Carolina history.” The USDA said crop losses caused by the storm could result in $7 billion in insurance payouts.

“Farmers have such a tremendous capacity for loss,” Nelson said. “Everyone in the area suffered, but some could still go to work if they had an office job or worked remotely, right? Farmers’ total livelihood in addition to their very homes may have been impacted, devastated or lost.”

‘As Soon As The Storm Hit, Calls Were Made’

Nelson earned a bachelor’s degree in animal science from NC State University intending to pursue an advanced degree in veterinary medicine, but she took time off to work at an industrial farm, and her life went a different course. After a time, she enrolled in nursing school.

Years later, “in about 2020, I decided that I would like to concentrate on helping people improve their health before getting sick, so I went back to school to become an integrative health coach.”

She was hired by the institute as a registered nurse. Today, she conducts health screenings and fit testing for personal protective equipment. She also extends herself to farm families and communities for additional health needs, such as mental health and community support.

“The members of the institute are all familiar with farming in some sense, so they are more aware of the needs of this special group of people,” Nelson said. “As soon as the storm hit, calls were being made, visits arranged, connections made between those who needed and those who had resources to give, needs were assessed, and teams made with organizations across the impacted areas.”

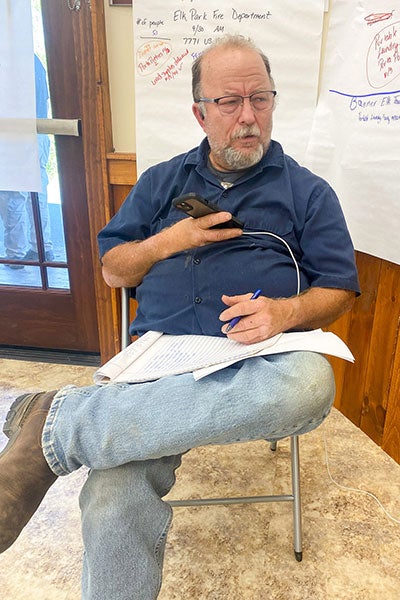

One of the fellow farmers with whom she works closely is Jerry Moody, a cooperative extension director for Avery County.

“There are going to be massive changes in our industry because of this,” he said, referring to the damage to farms and farm families caused by Hurricane Helene. “The amount of devastation for us was incredible. Talking with incidence management teams, the ones out in it, they said this is the worst devastation any area they’ve seen has experienced.”

Farms as an industry and a use of land had already been shrinking. Since 2017, there has been a steady decline nationally in both the number of farms (down 7%) and farmland (down more than 2%), according to the USDA (PDF).

But North Carolina has the second largest rural state population (PDF) in the U.S. More than 1 in 3 North Carolinians live in rural areas. For a state with a gross domestic product of between $550 and $600 billion, roughly one-fifth, or $111 billion, is produced by agriculture.

‘I Could Hear the Darkness in Their Voices’

Jerry Moody is a cooperative extension director for Avery County. (Contributed photo)

“The Agromedicine Institute reached out to us and asked what we needed,” Moody said. “It didn’t dawn on me that people would just fill up tractor trailers with food and water and send it up here without any destination for where it would go. You’re just sitting outside the office and here comes a load of apples. Here comes potatoes. Here comes tools or equipment. It was amazing, the generosity of everybody.”

One such delivery arrived care of Jessica Wilburn, a nurse coordinator at the institute. She and her husband used their Uwharrie Ridge Farm facilities and equipment to gather and deliver supplies with the help of the Randolph County farming community.

Western North Carolina farms are generally small, family-owned operations. They average about 103 acres in the storm-impacted area, growers of apples, sweet potatoes, Christmas trees and cucumbers along with livestock. The average age of such growers is about 58 years.

Farming is one of the most dangerous occupations in the country. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports there are 23 work-related deaths per 100,000 agricultural workers – seven times higher than the national average for workers.

Farmers also face high rates of depression and an elevated risk of death by suicide.

For this reason, Moody is keen to make sure mental health care is available and promoted, something the institute has made a pillar of its health outreach.

“I could tell, calling and checking on farmers” after Helene, “they weren’t their happy and chipper selves — I could hear the darkness in their voices,” Moody said.

‘Building Resilience into Our Communities by Focusing on Mental Health’

The 2018 Farm Bill addressed the existential threats to farmers and how it impacts them personally when it funded “stress-assistance programs” across the nation. One such program that evolved out of the institute’s Tape and Twine program was the North Carolina Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network (FRSAN-NC).

North Carolina Agromedicine Institute Interim Director Alyssa Spence loads the back of her vehicle with supplies headed for Western North Carolina.

Through the program, the institute offers provider education and mental health literacy education (for example, QPR, CALM, ASIST, Youth Mental Health First Aid, Adult Mental Health First Aid, and SafeTalk), and mental health support services accessed through the NC Farm Help Line and coordinating counseling services.

“Our approach considers evidence-based barriers to care — barriers identified by the agricultural community,” said Alyssa Spence, interim director of the institute. “That might be stigma surrounding mental health needs or desire for anonymity. It might be simply access, or time away from the farm. There’s even research that suggests mental health providers are disconnected from farm culture. That’s a barrier.”

FRSAN-NC is funded by the departments of agriculture at the state and federal levels, the Tobacco Trust Fund Commission, the Corn Growers Association of North Carolina, the state Farm Bureau and Farm Credit Associations.

“FRSAN-NC integrates strategies designed to overcome barriers and provide agriculturally competent mental health services and support,” said McKayla Robinette, FRSAN-NC coordinator. “Our ultimate aim is to build resilience into our communities by focusing on mental health, well-being and safety.”

Nurse Amy Nance Nelson said she’s been asked how to help western North Carolina, and her advice to anyone who will listen is this — “buy their products.” Consider an agritourism stop to the area. Consider buying local.

Building resilience to unbearable stress is something she’s folded into her care for the community, although screening for hypertension and diabetes and fit testing for personal protective equipment are her main duties.

“Last year at the farm show, a guy came up, a grower, and he said, ‘Y’all saved my life last year.’ That’s not uncommon, that someone will let us know that we helped him catch X, Y or Z.”

For every grateful patient, though, there are many more farmers with a new diagnosis or a troubling biomarker who must seek treatment but do not, Nelson says. And the institute’s efforts go on.

To learn more, including an overview of the institute’s programs, visit NCAgromedicine.org.