Eyes on the Skies

From early warnings to disaster preparedness, meteorologists inform and educate

Austin Mansfield

At age 4, Austin Mansfield ’17 watched from his Farmville home as Hurricane Floyd knocked down trees and flooded eastern North Carolina in 1999.

“I was just so curious of what happened, why it happened, when is it going to happen again?” Mansfield says. “That curiosity never left. I’m still wondering when the next weather event is going to approach.”

Today, Mansfield observes all kinds of weather as a meteorologist with the National Weather Service. He keeps 10 million people updated — whether it’s sunny and 70 or severe storms are approaching — in a region that includes Washington, D.C., and Baltimore.

“I am in the business of protecting life and property,” he says.

Weather affects everyone, from the farmer who’s praying for rain — or for the rain to stop — to families planning that weekend getaway to the beach. Yet severe weather — hurricanes, tornadoes, flash flooding, thunderstorm downdrafts — can bring death and property destruction. Like Mansfield, Jesslyn Ferentz ’17 is a product of ECU’s applied atmospheric science program. She’s the weekend morning meteorologist at WZVN ABC7 in Fort Myers, Florida.

“I get to nerd out all the time,” says Ferentz, who grew up in Harrisburg, N.C. “Being a broadcast meteorologist, it’s a new adventure every day. It never gets boring. I have an outgoing personality and love weather, so I combine the two to give a fun forecast to viewers.”

In her three years working in Florida, she’s forecast three tropical systems in her region. Seven of the 10 most active hurricane seasons in the Atlantic basin have occurred since 2005.

“I almost go into tunnel vision,” she says of hurricane forecasting. “I know what needs to get done, and my goal is to keep people prepared and informed with every update. When you prepare, you don’t panic. That is the main goal when covering tropical systems, to remain calm and informational.”

For her, Hurricane Ian stands out, a 2022 storm that hit the Florida Gulf Coast with 150-mph winds.

Austin Mansfield ’17 releases a weather balloon. A radiosonde attached to the balloon collects data such as temperature, dewpoint, humidity, and wind direction and speed that is used in forecast models.

Warming trend

- Earth’s temperature has risen about 2 degrees since 1850.

- The rate of warming since 1982 is more than three times as fast per decade as compared to previous decades.

- 2023 was the warmest year since global records began in 1850.

- The 10 warmest years have all occurred from 2014-2023.

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

“I’ll never forget the sound the building was making and debris hitting the roof. It was horrifying to say the least,” she says. “Even with all the training and other tropical systems that I’ve covered, nothing can prepare you emotionally for a major hurricane like Ian.”

Despite the damage a hurricane can bring, Mansfield says winter storms may be harder to predict because of the large number of variables. He recalls a 2022 winter storm that snarled traffic throughout northern Virginia and Maryland.

“I disliked snow very much at that point,” says Mansfield, who has worked for the NWS for four years. “Wintry precipitation forecasting is one of the hardest things to get right, especially in the Mid-Atlantic, because temperatures really fluctuate around here, and all of the precipitation types play a role in nearly every event we get here. I’ll stick to my severe weather and tropical cyclones.”

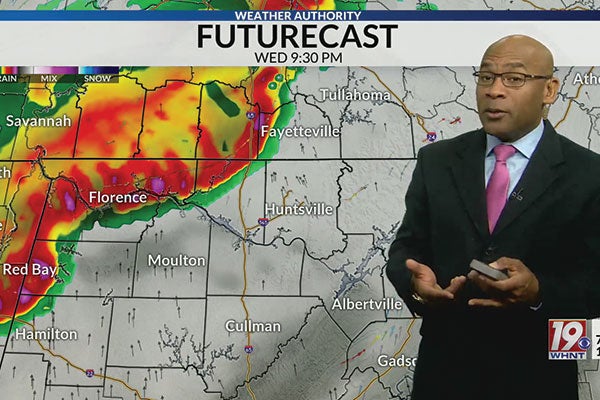

Meteorologist Ben Smith ’96 at WHNT News19 in Huntsville, Alabama, agrees that snow can be difficult to forecast.

“Terrain can play a role,” he says. “Mountains can enhance snowfall; they can also block it. When you have a forecast area that is large, not everyone will see the same thing. Percentages, precipitation type will vary. There are no guarantees in anything. I had a situation two years ago where half of a county got 6 inches of snow, and 9 miles down the road, they didn’t get anything.”

Smith, who last year won a regional Emmy award from the Nashville/ Midsouth Chapter of the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences in the Weathercast Category, says technology has helped overcome some of those forecasting obstacles.

“Accuracy has improved,” he says. “We use model data that goes out up to two weeks to forecast. Each product has strengths, weaknesses and biases. Timing and intensity of precipitation, storm tracks, temperature variability all play a role in the forecast.”

One of his most vivid memories is the 2011 super outbreak, a string of tornadoes that stretched from Texas to New York.

“That was a day I will never forget,” he says. “The National Weather Service in Huntsville, Alabama, issued 92 tornado warnings in a 24-hour period. We were on the air for 18 hours straight. There were 62 confirmed tornadoes in the state, and we lost over 250 people. I personally tracked two EF5 tornadoes with winds over 200 mph that afternoon.”

Helping and inspiring others

Considering ECU’s motto, Servire, all three feel a responsibility to serve the public through their forecasts.

“I cannot think of a greater honor than to serve some of the most important people in our country every single day,” Mansfield says. “As a public servant, my job is crucial in keeping the public safe and prepared.”

“I love helping people get their day started,” says Smith, who’s the morning meteorologist at WHNT. “I have had a passion for weather since grade school. I did the weather on the morning announcements in high school. I love it because it’s different every day and the challenge of looking into the future. Talking to the kids at schools is fun as well. Community outreach is really important.”

Ferentz, who provides forecasts on air and through social media to roughly 1.5 million Floridians, also values her interactions with youth.

“It’s an amazing feeling to be a role model,” she says. “I’ve had many young women come up to me saying, ‘I want to be just like you.’ Motivating the next generation of strong women in STEM careers is so rewarding.”

Forty years ago, the night that ‘didn’t seem quite right’ was one of the state’s deadliest weather events

To hear Jim Smith describe it, the late afternoon of March 28, 1984, didn’t seem ominous, but kind of nice – if a little odd.

Greenville’s The Daily Reflector from March 29, 1984, tells of the previous day’s destruction.

“We commented on how still it was,” says Smith, who was chair of the ECU philosophy department at the time. He and two other faculty members were driving to teach night classes at Havelock High School. “It felt weird. The temperature, it was very warm, in fact, even hot for the spring. There was no talk of a tornado as I recall. We didn’t think there was any danger.”

But that day, 40 years ago, turned out to be one of the deadliest in state history. A low-pressure area that started in Texas the day before had moved northeast. Together with a warm front from the Gulf Coast, those systems spawned a devastating seven-hour string of 24 confirmed tornadoes from north Georgia to northeastern North Carolina. An F4 tornado slammed through Greene, Lenoir and Pitt counties, damaging part of ECU’s campus, killing 16 and injuring 153.

“We were driving back, and I still remember the smell of pine,” says Smith, now 80 and retired but still teaching part time. “It was crazy. It was like we had just sawed down a pine tree and stacked it in the back of the car. It was that intense.”

When Smith got to his home near Simpson, he had already passed a number of police and rescue vehicles with their lights blazing. His wife told him she had heard a sound like a train. The tornado had passed within a couple of miles of their house.

“We didn’t get the details until the next day, but we had no idea when we went to bed how terrible it was,” he says.

The United States experiences about three quarters of the world’s tornadoes, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – about 1,200 each year. Only about 5% cause significant damage or deaths.

Susan Bailey, an administrative support specialist in the College of Nursing, was 14 in 1984. Her father, Tom Sayetta, was a physics professor.

“I remember how weird the weather felt outside, maybe because it was March, but there was a lot of humidity in the air, and something just didn’t seem quite right,” she recalls. “There was no sort of Doppler radar or anything like that, not like there is today with all the warnings we get. It was really quick between when the warnings came and when the storms actually hit.”

One of those killed in the storm was Faye Creegan ’65, a history teacher at E.B. Aycock Junior High School and a graduate student in the history department at ECU. Smith’s son and Bailey were students of hers.

A 100-year flood happened last year, so it won’t happen for another 99 years, right?

Not exactly. Experts use the term “100-year flood” to simplify the definition of a flood that statistically has a 1% chance of occurring in any given year, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Says Tom Rickenbach of ECU, “A Hurricane Matthew (2016) or Hurricane Floyd (1999) or Hurricane Florence (2018), they’re happening more frequently, and the statistics are such that it’s about one out of every 10 years you’re going to see a flood like that.”

“He loved her,” Smith says. “He thought she was one of the best teachers he had ever had.” Creegan was 40. Her home near Portertown Road was one of hundreds obliterated along the 484 miles of destruction. The Faye Marie Creegan Memorial Scholarship has benefited more than 35 College of Education students who plan to teach social studies.

“I remember we went to school the next day,” Bailey says. “Miss Creegan did not show up that day. I remember how they announced it toward the end of school that she had passed away. To actually know somebody who died who we were really close to, that was shocking at such a young age.

“I grew up here, and we had never had anything like that with so many deaths and destruction from a tornado. I remember we drove out toward Ayden, and the traffic was just incredible. Everyone was driving by to see what had happened because we had just never had anything like that before. I remember seeing how all the trees were just snapped and all this stuff was just everywhere. I had never seen destruction like that.”

The 1984 tornadoes aren’t the only ones hitting a milestone this year. Fifty years ago, a handful of twisters struck western North Carolina during the April 3-4, 1974, tornado super outbreak, killing five and injuring 45. As many as 148 tornadoes struck a total of 13 states and the Canadian province of Ontario, killing 315, injuring nearly 5,500 and causing $843 million in damages. It ranks as the worst tornado outbreak in history, according to tornado expert Thomas P. Grazulis’ Outbreak Intensity Score.

On Feb. 19-20, 1884, tornadoes stretched from Edgecombe County to the mountains during the Enigma tornado outbreak, when as many as 60 struck 10 states from Mississippi to Indiana. One powerful tornado swept through the Rockingham area, killing 23 – the deadliest in state history.

Ben Smith ’96, a meteorologist at WHNT in Huntsville, Alabama, says predicting tornadoes is still difficult, but technology has improved forecasters’ ability to help people get to safety.

“We can now detect rotation in storms with products like base velocity and storm relative velocity,” he says. “A newer product called the correlation coefficient helps in debris detection in tornadoes. These all help in getting the word out sooner to help people to get to a safe place in a tornado.”

– Doug Boyd and Ken Buday

Forecasting the future

Ben Smith ’96 delivers forecasts for a half million people in the Huntsville, Alabama, area.

Jesslyn Ferentz ’17 updates viewers on the progress of Hurricane Eta from the Florida Keys in 2020.

Tom Rickenbach, a professor of atmospheric science at ECU, motivates his students to go beyond the day-to-day forecast. He conducts research on how precipitation systems control and respond to changes in climate. His goal is to use science to help inform decisions, noting climate data that shows increasing temperatures. Earth’s 10 warmest years on record have all occurred in the last decade, with 2023 being the warmest ever.

“So, if you were to take Raleigh and move it down to Miami, that’s what 10 degrees of warming would feel like,” he says. “Is it the end of the world? Absolutely not, but is it different? Can we adapt to that? Of course we can. But is it a change? Does it have implications for water resources, agriculture, maybe property values, health and well-being for certain vulnerable populations or species habitat? Those are all issues that are certainly important in a change like that.”

He points to research that indicates a northward shift in meteorological tropical weather patterns that produce precipitation, which is tied to a warming planet. He compared it to the steroid era in professional baseball.

U.S. hurricane strikes by decade

- 1961-1970: 12

- 1971-1980: 12

- 1981-1990: 15

- 1991-2000: 14

- 2001-2010: 18

- 2011-2020: 19

- 2021-2023: 4

Source: NOAA

Most Active Hurricane Seasons, Atlantic Basin

- 2020: 30

- 2005: 28

- 2021: 21

- 2012, 2011, 2010, 1995, 1887: 19

Note: Number includes tropical storms and hurricanes

Source: Colorado State University

“Statistically, you can look back at the 1990s and early 2000s and see more home runs were hit. And in a similar way, when you add heat to the atmosphere, you increase the likelihood that there’s more extremes and precipitation, heavier rain events, sort of like taking steroids means more home runs,” he says.

Just like every baseball player didn’t take steroids, not every storm is going to have catastrophic results. Still, Rickenbach looks at statistics that show the chances of 100-year floods have increased. But there’s no need to panic. Instead, Rickenbach says we simply need to adapt.

“It’s not like we can’t live here anymore. It’s nothing like that,” he says. “These are changes that we can mitigate, and we have to adapt to. It’s going to mean changes in the patterns of where exactly we live and what kind of crops we grow and the timing of our crop rotations, how we fix roads and the kind of investments we have to make in sand replenishment at the beach and things like that. For me, that’s sort of the bottom line of climate change in our region.”