SPEECH PARTNERSHIP

Partnership with Alaska and Arizona universities brings rehabilitation services to remote communities

Erin Baginski lives about as far from eastern North Carolina as a person could drive to, but she’s every bit a Pirate and represents a pair of very successful partnerships with universities in Alaska and Arizona that are supplying qualified speech-language pathologists to some of the most rural areas of the United States.

Alaska is 586,412 square miles, with 240 remote villages and nearly three quarters of a million people. There are only 404 licensed SLPs. Eighty percent of communities in Alaska are not connected by roads.

In the mid-1990s, North Carolina mandated that speech-language pathologists (SLPs) would have to be trained to the master’s degree level, and appropriated two faculty positions at each university that trained SLPs.

Kathleen Cox, interim dean of ECU’s Graduate School.

Dr. Kathleen Cox, the interim dean of ECU’s graduate school and a former professor in the College of Allied Health Sciences (CAHS) speech-language pathology program, was hired into one of those newly allotted jobs. Several years after she joined Pirate Nation, the state asked ECU to create a distance education programs to help bring North Carolina’s bachelor’s educated providers up to the state standard.

The faculty at CAHS relished the challenge, but the implementation of the program was decidedly of its pre-internet, pre-streaming video era.

“We started teaching our classes in a Brody School of Medicine distance learning classroom. Ten students, between three sites, would meet at a regional location, like a community college library, Tuesday or Wednesday nights and the classes were televised live,” Cox said. “At some point we graduated to not having it real time and recorded our lectures. We mailed videotapes, the students mailed them back. Assignments were mailed and we had to change our syllabi to say, ‘postmarked or turned in by such and such a day.’”

Eventually internet connectivity caught up to ECU’s vision for how distance education could revolutionize teaching students who wanted to learn and make a positive impact on their communities without having to attend in-person classes in Greenville.

Path to Piratehood

Baginski was born and raised in southern California. She ran cross country for the University of Hawaii but transferred back to the mainland and graduated from Sacramento State University. After graduation she moved to Colorado where she taught snowboarding in winters, peppered with some international travel, and chased fires across the western states during summers working for the U.S. Forest Service.

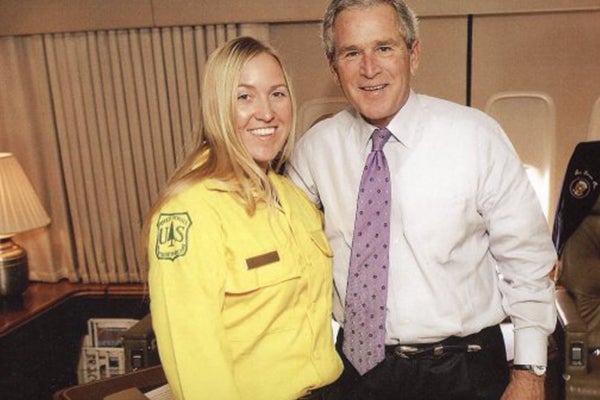

Her career was on a rocket’s trajectory — she received an award for being the most physically fit woman in the fire service and was asked to join President George W. Bush on a tour of western fires — until a medical condition doused the flames of her burgeoning career.

“I ended up with Type 1 diabetes and that was a real shock because I had been through the fire academy and my hope was to go on to be a smoke jumper,” Baginski said.

Erin Baginski flies on Air Force One with then-President George W. Bush.

ECU speech-language pathology student Erin Baginski watches the the Iditarod Trail sled dog race in Alaska. (Contributed photo)

With her plans set askew, Baginski leaned on her child development degree and moved to Indiana to work as a speech assistant with kids in behavioral health treatment and start working on a master’s degree to be speech-language pathologist. After a few years of school and work she was burned out and needed a break. She accepted a job offer as a speech assistant in Alaska and hit the road.

“I was on my own and I was camping along the way, but it ended up being a great adventure,” Baginski said.

In Anchorage, Baginski fell in love with Alaska, got married and found a community that needed her skills and motivation. She decided to complete the graduate education she had started to be a solution for the Alaskan communities that had accepted her.

That’s where a school on the other side of the country became a factor.

Partnerships in Alaska and Arizona

Emily Brewer, a certified speech-language pathologist and program director for the Master of Science degree in communication sciences and disorders at ECU, said that the University of Alaska Anchorage wanted to service students in rural areas but didn’t have the capacity.

Officials at UAA proposed partnering with ECU which solved needs for both schools. ECU was eager to increase enrollment but needed help with clinical placement for students that far away and UAA could work with Alaska’s SLP community to get students “clock hours,” the hands-on training with patients.

“Students get 12 clinical credits and all of their clinical clock hours, a minimum of 375, through UAA. Then prior to graduation they transfer those 12 credits into ECU and their degree comes from ECU,” Brewer said.

By 2014 Arizona State University was in the same boat as Alaska — desperately wanting to graduate SLPs to serve their state, and its unique patient populations, but were working with the same faculty limitations as UAA.

“The director at Arizona State said, ‘We have a real need in these more rural parts of Arizona for the students who can’t just leave their homes for two years to complete a master’s degree with us,’” but can find clinical placements and take online course work, Brewer recounted.

Karen Gallagher, program director of the speech-language pathology program at the University of Alaska Anchorage

Karen Gallagher, the speech-language pathology program director at the University of Alaska Anchorage, was previously part of the SLP program at Arizona State. She said the successes in Alaska were noticed by ASU faculty and a partnership with ECU would be a similarly good fit. Arizona had speech-language therapists, but members of the career field needed master’s level training.

“We needed to reach out to people who were practicing in schools without the level of education they needed for certification and licensure. The partnership allowed ECU to provide the didactic coursework and ASU to provide the clinical training,” Gallagher said.

Now in Alaska, Gallagher said the state is starting to see dividends from the program’s successes.

“We provide our students with a blend of programs that give them extra training in mental healthand early intervention, and I feel like we’re able to offer a robust clinical experience because I don’t have to figure out how to build an accredited graduate program,” Gallagher said.

ECU accepts five students each year from the Alaska and Arizona partnerships, with about 15 students from each school enrolled at any time.

Internet access in extremely remote areas of Alaska and Arizona may be spotty at times, but it is worlds away from where the ECU SLP distance education program began. The immediacy of on-demand, asynchronous classroom spaces means that ECU’s world class education can be had across the country, in even the most remote locales.

Those same internet connections also carry the promise of extending the expertise of ECU-trained SLPs through telehealth sessions. Rather than hours long bush plane rides or dangerous and time-consuming drives, patients and providers in Alaska can meet virtually, further extending the precious resource of a certified SLP.

Those same internet connections also carry the promise of extending the expertise of ECU-trained SLPs through telehealth sessions. Rather than hours long bush plane rides or dangerous and time-consuming drives, patients and providers in Alaska can meet virtually, further extending the precious resource of a certified SLP.

Because the enduring success of the partnership, many of the speech-language pathologists working in Alaska are connected to ECU in some way. Baginski said it can be hard to feel connected to the program, but she and two other members of her cohort worked together over the summer, a “great bonding experience” that she cherished.

Brewer said that the mix of distance education students enrolled in the program through ECU and Alaska are about the same — largely nontraditional students and those who have started a careers and are increasing their qualifications. The students in Alaska might skew a bit younger though.

“There are students who have just come right through and chose the distance education model because it fits the remoteness of their location better,” Brewer said.

Empowering communities

Most of the residents of Alaskan villages speak English, which is a double-edged sword; it is easier for English-speaking SLPs to provide services across the state, but it also means that native languages and cultures, are threatened. The same is true for communities in Arizona and across the western U.S.

The leaders of ECU’s SLP bilateral partnerships agree that working with native communities to provide services in native languages is an important part of their work.

“Hopi and Navajo nations in Arizona share some of the same challenges with our Dena’ina and Athabascan native Alaskan communities where none of assessment or treatment research is based on their language. I can take a standardized language assessment off the shelf and go test an English speaker in Arizona or North Carolina or California and it is normed on that population, and I can rely on those results. The same is not true for native Alaskan speakers,” Gallagher said.

Gallagher said the language and travel challenges that SLPs face in Alaska can be mitigated by training speech-language pathology assistants (SPLAs), who can help to translate, and understand the correct expression of, tribal languages as well as physically be in remote communities to participate in telehealth experiences.

“It takes me five to seven years to grow an SLP and one to two years to grow an SLPA. We need them in their communities to say ‘No, this is how it’s pronounced in my dialect, this is how it’s said in my language,’ and they can collaborate and work together to modify and adapt. We have to rely on the native speakers,” Gallagher said.

Erin Baginski hikes in Alaska. (Contributed photo)

The challenges of reaching communities in Alaska that need help are staggering, Baginski said. Because most communities can only be reached by bush plane or boat, if she were able to raise the funds for a service expedition to Alaska’s Aleutian Islands, it would require weeks or months of travel and she would have to bring everything she would need with her: food, medicines and likely shelter. Village residents, who are in the most need of medical and rehabilitates services, are subsistence hunters — there aren’t really grocery stores.

“There isn’t a place to stay. I’d have to sleep on the floor in a school and pay $100 a night,” Baginski said.

Adding to the general lack of resources in rural areas, climate change is making a tough situation that much tougher.

“Missionaries came in and built schools and summer camps, and villages have been set up in their summer camps, and now they’re flooding due to global warming and melting of permafrost,” Baginski said.

ECU’s Cox made several trips to Alaska during her time teaching SLP students and is in awe of the resourcefulness of the Alaskan Pirates.“The people of Alaska are just so much more resilient than I think anyone who’s lived in the lower 48. Everything is harder there. We had a student once that lived in a small village where the internet bandwidth was rationed by the village elders. She called me and said the village elders told her to stop her schooling and asked if there was any way to let her download the lectures, which we didn’t do because it’s intellectual property, but for her, we made an exception,” Cox said.

Brewer said the need for speech-language pathologists is glaringly obvious, but in relatively well-resourced areas like North Carolina providers are overburdened with work.

“Even here in North Carolina you have SLPs in the school system who have a caseload of 60 and70 students because there aren’t enough speech-language pathologists in those in those positions,” Brewer said.

Gallagher said the incredible logistical challenges that health care providers, and students, face inAlaska mean rewarding overseas service experiences, like trips to Africa that her Arizona State SLP students raised funds for, aren’t necessary. Instead, her Alaska students plan similar trips to the remote areas of their own state.

“We don’t need to go to Africa. Our students must pack in their own food, their own supplies, to not use up the resources in the communities we serve. It’s a way of preserving what is Alaskan and what these communities need,” Gallagher said.

Cox said the bilateral agreement with UAA helps to not only get trained providers into areas of Alaska and Arizona that are desperate for help, but Greenville-based students also benefit from exposure to the realities of working with peers who are from different cultures and time zones.

“Every once in a while people would say, ‘You know, the diversity in this program isn’t broad enough’ and I tell them you haven’t looked at the Alaska numbers,” Cox said. “When I did group projects, I mixed them and they would have to figure out time zones and how to collaborate, which is essential to modern health care.”