FIRST RESPONDER SIMULATION

State law enforcement and first responders use Brody simulation center for medical training

The clinical simulation center at East Carolina University’s Brody School of Medicine is usually peopled with fresh-faced students in scrubs and running shoes with tousled college-kid hair.

During the first week of the fall 2023 semester, however, the trainees in the school’s simulation center wore T-shirts with state trooper logos and utility belts on their hips.

On Aug. 23, the Brody simulation center welcomed more than 40 members of North Carolina’s law enforcement and first responder community to refresh their medical skills ranging from how to treat burns and heart attacks to the basics of assisting in an unplanned birth on the side of the highway.

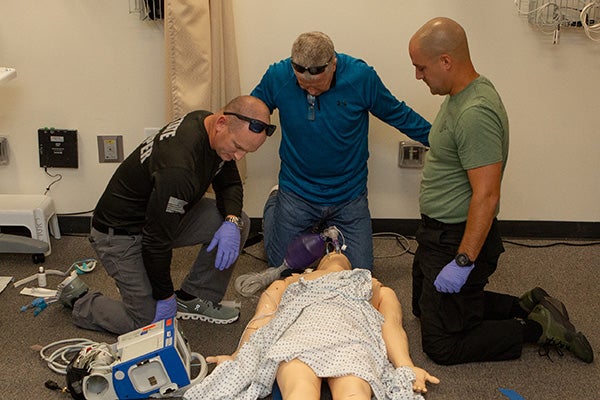

Current and retired North Carolina law enforcement and first responders practice airway management techniques at the Brody School of Medicine simulation center.

Sean Johnson is North Carolina’s State Highway Patrol (SHP) director of training and manages more than 1,700 state troopers who need medical refresher training annually to stay qualified for their positions. Johnson, who worked the road for years before assuming his new role, knows from first-hand experience that being proficient in basic emergency medical response as a law enforcement officer is crucial because a car accident or other catastrophe could literally be just around the corner.

The highway patrol’s medical director — a doctor who oversees nine state government agencies including the Office of the State Fire Marshal, State Bureau of Investigation and Wildlife Resources Commission — has statewide jurisdiction to render medical care, making the SHP unique among first responders in North Carolina.

Johnson said that one of his urgent concerns is making sure that troopers are able to provide medical care before EMS workers arrive because of the uptick in the number of assaults on law enforcement officers in recent years, which might result in troopers rendering aid to those who tried to assault them. About a month ago, Johnson said, a law enforcement officer stopped to help a motorist change a tire and was shot by a career criminal.

“His vest saved him; He shot him with a .44 Magnum. But as soon as the trooper shot the suspect, he transitioned into patient care and tried to treat the guy. That’s the way we train them,” Johnson said.

The more common occurrences of vehicle accidents can be no less stressful and could require a Swiss army knife of medical response skills on a daily basis.

“You could go around a curve and there is a car wrapped around a tree and 911 has not even been activated so you’re talking about 10 to 15 minutes of waiting or treating somebody by yourself until higher level care gets there,” Johnson said. “Keeping these folks trained with the ability to deliver patient care is very important and we’re trying to grow our system.”

Johnson said one of the skills that annual training, like his troopers received at Brody, has improved upon is helping law enforcement to distinguish between a person who is experiencing a medical emergency, like a stroke or medicine imbalance, rather than being impaired behind the wheel.

“Troopers may stop somebody they think is drunk when they’re having a diabetic emergency or won’t respond, they may be having a complex partial seizure,” Johnson said. “Training in a controlled environment, where feedback can be given, is a game changer for public safety.

“The community is very appreciative when they get to see a side of a trooper that they’re not expecting. This is definitely beneficial to everybody.”

Value of training

Joe Bright Jr. spent most of his career with the State Highway Patrol protecting the N.C. State football team and its coach, but he bleeds purple and gold. He was an outside linebacker for the ECU football team in the run up to the Peach Bowl win in 1992 and after graduation was hired to provide security at the Brody School of Medicine while he completed law enforcement training. After a year with the ECU Police Department he moved to Raleigh and started working as a state trooper.

Bright said the training he received prepared him for the few instances where he was called upon to provide medical aid in uniform, but as a public servant his responsibility to the public didn’t end when he took his uniform off.

“Ask my wife. When I’m at Walmart or on the side of the road, just knowing what to do when someone has a medical emergency is important,” Bright said. “I use these skills for my safety team at church. Anytime we learn as officers and first responders the best thing for us to do is share that knowledge.”

Rebecca Gilbird, administrative director of Brody’s clinical simulation program, said the school has been working for several years to partner with the highway patrol to get troopers into the school for refresher medical training. The training is a public service that meet’s Brody’s mission of caring for the people of eastern North Carolina.

Brody’s simulation program is usually booked a year in advance because it primarily exists to train ECU medical and allied health students, medical residents and hospital staff, so getting a free day to accommodate law enforcement and first responder training is a rare luxury, Gilbird said.

“We started working with the state highway patrol last November; that’s how long we’ve had this on our calendar. We reserved the date and they’re coming back in November to do another round,” Gilbird said.

Benefit for the state

Lee Kennedy works for the Office of the State Fire Marshal. For his day job he assesses response capabilities of fire departments across a broad swath of southeastern North Carolina. He is often deployed to support state agencies during hurricanes and other natural disasters. In his spare time, Kennedy volunteers as a fire chief in Faison.

Annual training has improved law enforcement’s ability to distinguish between a person who is experiencing a medical emergency rather than being impaired behind the wheel.

“In my six years working for the state I’ve had it a couple of times where we’ve ended up having somebody get too hot or somebody having chest pains,” Kennedy said.

Kennedy said the dynamic mannequins used in medical training scenarios at Brody — the ones that respond to questions and present trainees with true vital signs — makes training more realistic and valuable to law enforcement and other state workers.

“Normally it’s just talking through situations or treating a mannequin that doesn’t respond so that was actually pretty cool,” Kennedy said.

Bright, the state trooper who finished his career as the first sergeant of the SHP Training Academy, said that while it’s not the primary responsibility of law enforcement to provide first aid in the field, the confidence that comes from keeping basic skills refreshed is invaluable, particularly in rural areas of the state.

“Some officers may be the first one on the scene and knowing what to do for someone who needs medical attention makes us feel that much more confident in our work,” Bright said.

Kimberly Farmer is relatively new to the highway patrol, having worked more than three years in Harnett County where she grew up, but has been an EMT for more than seven years. While the county is fairly rural, Farmer said, first responders usually make it to incidents that require medical intervention before she does. However, being trained and having periodic refresher training like the kind she received in Brody’s simulation center, gives her confidence to know how to care for those in dire medical circumstances.

“We’ve gone through a ton of scenarios in the short time that we’ve been here this morning. We really hadn’t been able to do this in the past couple of years which COVID played a large part in,” Farmer said.

Gilbird, the simulation center director, takes pride in helping members of another state agency be ready to care for those in need.

“It makes me feel good that we have trained personnel out there. If I get in a wreck or my parents get in a wreck — we’ve trained them,” Gilbird said.