Interdisciplinary research team tackles challenge of addiction recovery

An interdisciplinary team of health professionals from East Carolina University received a grant to study the impacts of the nationwide opioid epidemic — responsible for most of the state’s 11 daily unintentional drug overdoses — on North Carolina.

W. Leigh Atherton from the Department of Addictions and Rehabilitation Studies in the College of Allied Health Sciences and Chandra Speight from the Department of Advanced Nursing Practice and Education in the College of Nursing were awarded a $380,000 grant from the University of North Carolina Collaboratory Opioid Abatement and Recovery Research Program.

The ECU study has two main goals. Atherton and Speight will investigate the differences between the encouragement offered by addiction professionals and peers already in recovery who work to connect with those in need of recovery support. Second, they will analyze the challenges and successes to implementing peer-delivered treatment strategies in community organizations.

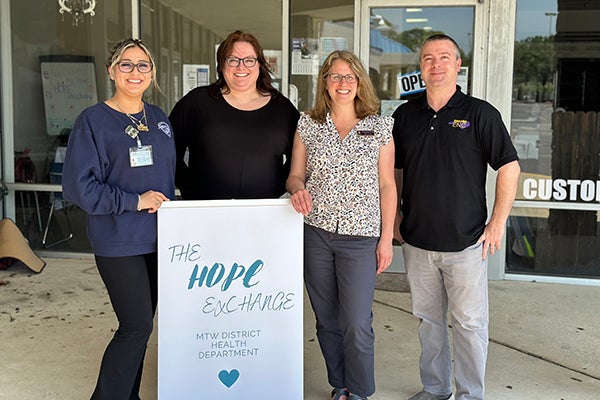

Yerlin Villegas, from left, Jennifer Perry, Chandra Speight and Leigh Atherton (left to right) work at a Hope Exchange needle exchange outreach event in Williamston. (Contributed photo)

“This is a novel and important approach in a place like eastern North Carolina,” Speight said. “Eastern North Carolina is rural and medically underserved. We explore how individuals with a history of substance use disorder who are currently in recovery can help people currently using explore treatment options. Such exploration is critical in our area, where we have both an opioid epidemic and a shortage of treatment providers.”

Data from the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services’ Injury and Violence Prevention Branch shows Pamlico, Scotland and Craven counties — all of which are located in eastern North Carolina — have some of the highest rates of opioid overdose emergency department visits in the state.

“The disparity of health professionals in rural eastern North Carolina as you get further and further away from Greenville and into areas that have health care provider shortage is even more rampant,” Atherton said. “So the access to a professional from community providers to even bring someone in is going be difficult, not to mention the cost of doing so.”

Atherton and Speight said that coupling their counseling and clinical nursing backgrounds will help them to make inroads with both community outreach organizations and individuals searching for recovery options that fit their needs.

“We have partnered with community organizations that serve individuals who use substances, including syringe exchange programs and community meal centers. We plan to recruit volunteers from these organizations and train them in treatment engagement methods,” Atherton said.

Overcoming the social challenges related to opioid-use disorder is another important part of the team’s research.

“Stigma around opioid use disorder both prevents providers from offering care and discourages individuals from seeking care in traditional spaces,” Atherton said. “Our research is exciting because we work with peers in a trusted space, where people are approached with respect and authenticity.”

Peer space

The researchers hope to have success in getting people to begin treatment processes by taking doctor visits out of the equation, which health care and drug treatment proponents previously believed were necessary to engage those who need recovery.

“There’s so much stigma and fear around treating individuals with opioid use disorder or individuals presenting for treatment. That’s what’s really exciting about this research into the peer space — we start to find a way for communities to work around this stigma,” Speight said.

Ultimately, the research could make a large impact on the future of the opioid crisis in North Carolina by increasing the overall number of individuals that are trained to engage in the conversation of receiving treatment. Eastern North Carolina has more than half of the state’s counties with the highest rates of unintentional opioid-involved poisoning deaths, according to the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services.

Ultimately, Atherton and Speight believe their project will provide a blueprint for other community organizations that wish to implement peer-delivery treatment engagement programs.

“Our overarching goal is to produce implementation-ready results,” Speight said. “Along the way, we will document the barriers experienced and how we addressed them. Importantly, our community partners will lead this work — as they know best what works for their communities.”