ECU medical students establish ‘doula-like’ volunteer program

Getting through medical school can be tough — long hours, books and tests, and more books. However, between classes and all-nighters, two students from the East Carolina University Brody School of Medicine have established a flourishing volunteer program to bring doula-like services to a region of North Carolina starved for birthing support.

The birthing companion program was started in October 2022 by Uma Gaddamanugu and Shantell McLaggan, both second-year Brody students and Schweitzer fellows. The Albert Schweitzer Fellowship supports graduate health professionals drawn from across the state who learn and work to address unmet health care needs in North Carolina.

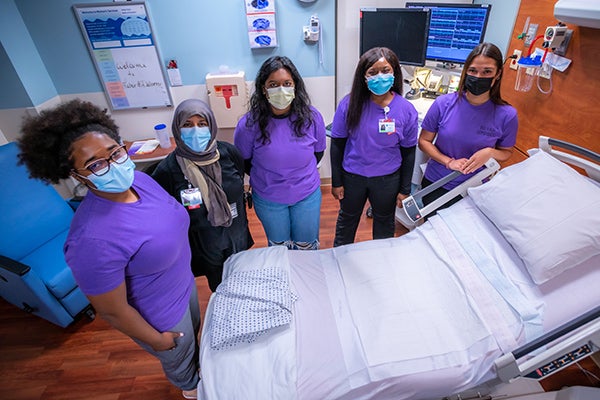

East Carolina University students volunteer as birthing companions at the ECU Health Medical Center in Greenville, North Carolina. (ECU Health photos by Joe Barta)

Gaddamanugu’s and McLaggan’s fellowship project is focused on improving birth experiences of high-risk pregnant mothers in eastern North Carolina through the free birth support program to add an extra layer of support for women in the birthing process.

Patient populations in rural parts of eastern North Carolina simply need more help, Winston-Salem native Gaddamanugu said, from prenatal care through the laboring process, and certified doulas are an expensive out-of-pocket resource for which most North Carolinians must pay out of pocket because health insurance often doesn’t cover the cost.

“We are the only hospital with a high-risk labor and delivery unit in North Carolina east of I-95. You think about how far some of these people have to travel, which makes it way harder for their support people to come with them,” Gaddamanugu said.

In February 2022, the North Carolina Institute of Medicine reported that the state’s maternal mortality rate was 27.6 per 100,000 births, which is slightly lower than the national average, but more than double the previous year’s rate of 12.1 per 100,000 births.

A 2021 study by the North Carolina Maternal Mortality Review Committee reported that 60 women died from pregnancy related causes from 2014-16. Of those, nearly 60% were from minority racial categories and more than one in three were from rural areas. What’s more troubling — the study determined that 70% of maternal deaths could have been prevented by changing “patient, family, provider, facility, system and/or community factors.”

The program

At first, the program had 18 volunteers, but since its inception in October 2022 the ranks of birthing support volunteers have doubled to 37. At the beginning of February, the volunteers assisted with more than 70 births, which is “way past our goal that we had initially set,” Gaddamanugu said.

Volunteers from the program come from a wide range of backgrounds, though most are medical or nursing students. Some are undergraduate students from main campus who want to be part of a program that serves the community. For now, the program is staffed almost completely by ECU students, though Gaddamanugu and McLaggan will soon hand the program’s day-to-day management off to first-year medical students who aim to open the program up to the public.

ECU student birthing companion volunteer Rachana Charla shares a moment with Sierra Chavez following the birth of her child at ECU Health Medical Center.

“Our program is very much modeled off a program at UNC. They’ve been doing that for about 10 years,” Gaddamanugu said. “A Wake Forest medical student started a similar volunteer doula program two years ago through the Schwitzer Fellowship. It’s just neat to see that it was possible with the structure of the organization to bring that program here, because there’s a whole different need in eastern North Carolina.”

Gaddamanugu stressed that the volunteers in the program, who support the labor and delivery services at ECU Health, aren’t certified doulas but rather are there to help during the immediate labor process. For one delivery, that might be a non-clinical, non-medical role — a friendly face and a hand to hold — and in other cases it might be running through the hospital to find a phone charging cable so a mother can stay in contact with her other children at home.

Leslie Coggins, a charge nurse on the labor and delivery unit at ECU Health Medical Center in Greenville, said the volunteer program has been a great success, both for the mothers in the delivery process as well as for students on track to become the next generation of health care providers.

“We’ve always had a great relationship with our residents, but now we have almost a pipeline — doctors, potential doctors, nurses, someone interested in birth and supporting birth in its natural function,” Coggins said. “To share that experience with up-and-coming providers and nurses who will be taking our places someday is huge.”

While the volunteer program is currently staffed by students, the student organizers and Coggins as the nurse manager of the labor and delivery unit hope to soon include members of the public. Those interested in volunteering should contact the program by emailing the program at ecudoulas@gmail.com.

Training medical professionals

The ECU version of a volunteer birth companion program is rooted in experiences both medical students had working as volunteers in hospitals in doula-like roles. Gaddamanugu volunteered during her time as an undergraduate at UNC; McLaggan, who is from Thomasville, spent several years after her undergraduate education working at the Cherokee Indian Hospital in western North Carolina and helped establish a volunteer doula program there.

Both students are interested in pursuing a career in obstetrics.

McLaggan’s mother told her from an early age that she was smart enough to be a doctor. After researching the requirements and being captivated by the science of medicine, she fell in love with the idea.

“I feel like I have the mental, emotional and the physical capacity to do something as strenuous as being a doctor,” McLaggan said. “Because I have those qualities, I feel like it’s my obligation to become a doctor and serve people to the maximum of my abilities.”

Medicine was also a calling for Gaddamanugu, who said that the challenge is humbling but she sees a future where she can make a difference by “maternal and child health disparities in our community” which fit the impact that she hopes to make in the world.

She said that the experiences at the bedside have colored the conversations that she has with her medical school peers about the experience of medicine from the patient’s perspective.

“We know birth is hard, but here is what it really can look like,” Gaddamanugu said. “The U.S. has an awful maternal mortality crisis, and we can hear those numbers all day long in school, but the numbers don’t mean anything until you see it in person, and you realize some of these patients are extremely sick.”

For Kerianne Crockett, ECU Health OB/GYN and Brody clinical assistant professor, the program has clear benefits for the patients she serves. She has heard from patients who appreciated having another source of support during their delivery.

“Delivering a baby is one of the most exhausting, exhilarating, sometimes scary experiences of a patient’s life,” Crockett said. “There is good evidence that patients with a continuous support person present throughout labor — whether that person is a family member, a spouse or a doula — have better birth outcomes, including lower rates of cesarean delivery. I am so proud that our bright, compassionate, empathetic medical students are now able to be that continuous support person for all kinds of patients, including those who otherwise would not have had anyone besides the medical team there for their delivery. “

Student involvement in health care delivery, and the unique perspectives students offer patients, is a hallmark of a large academic health system like ECU Health. As students learn from the clinical experience of providers at ECU Health, they are empowered to innovate and bring ideas to the table that lead to better patient experiences and brighter outcomes.

“As an academic health system, our medical students help to enrich the patient experience with their energy and ideas,” said Angela Still, senior administrator of women’s services at ECU Health Medical Center. “The birthing support volunteer initiative is a great example of how Brody students go beyond the walls of the classroom and make a direct impact on the patients we’re proud to serve.”

Serving eastern North Carolina

Sometimes the most important support that a birthing companion can provide comes from skills that can’t be taught in a formal doula class.

McLaggan remembers one time she volunteered with a woman who had a number of kids already — the most recent born by C-section. The medical staff recommended another C-section, which the woman was reluctant to agree to due to the complications she had with the previous birth. The challenge that McLaggan was able to help resolve wasn’t convincing the woman to have a C-section, but rather just communicating with her at all. The woman was Haitian and spoke Haitian Creole and little English.

“I happened to speak French, which is very similar to Haitian Creole, so she was able to communicate to me, where she was coming from and what her needs were,” McLaggan remembered. “I was able to bridge that gap and she ended up delivering naturally. I felt so honored and privileged to have been in the room.”

Another of the volunteers in the program has similar experiences with language gaps being a hindrance to quality health care. An undergraduate student recounted to Gaddamanugu how, growing up in eastern North Carolina, she was always saddled with translating for her mother and siblings during medical appointments — a task that shouldn’t really be shouldered by a young person. The student volunteer said, though tears, that she was so grateful to be able to translate for delivering mothers because she knew first-hand the constricting fear and anxiety of being language-locked in a stressful medical situation.

While the language capabilities that some students bring to the hospital bedside are important, Coggins said, patient populations in eastern North Carolina are getting sicker, which often requires the health care team members to devote their attention to the physiological status of the patient.

“We try to promote natural delivery as much as we can,” Coggins said, but sometimes the medical conditions of the mother and baby require doctors and nurses to focus on the immediate illness. “One-on-one support is essential with our patients. A lot of times our sick population are not from around here and don’t have the support system in place, so this is an added benefit so our nurses can focus on what is medically happening and where we need intervene.”

Gaddamanugu is awed at the privilege of being present at a birth.

“I’ve cried every single time; it’s one or two single tears, but they were C-section babies and you could sense the relief in the (operating room) the moment the baby comes out safe and healthy,” Gaddamanugu said.

McLaggan has known that being in the room during the birthing process is what she has wanted to do since before kindergarten. She’s seen a handful of births as a volunteer and continues to be amazed by each one.

“Words don’t describe how amazing childbirth really is. I get so overwhelmed with emotion when I see 37 to 40 weeks of work and love going into this child that is coming into the world,” McLaggan said.