GAMING HEALTH EDUCATION

ECU-developed game uses tech to teach nursing, medical students

Sometimes gaming doesn’t mean playing a game.

In June of 2022, Josh Peery, a game designer and instructional technology consultant for East Carolina University’s College of Nursing, was asked to speak at the Serious Play conference in Orlando. A conference about games isn’t the first place you’d expect to find a nursing school employee, but Peery wasn’t there to talk about nursing students playing first-person shooter games or the latest zany Mario Brothers adventure.

“I keep getting invited to speak at conferences because in the health care sector, we are one of the few colleges that are developing serious games in house and using them at the same time,” Peery said.

Serious games, Peery said, are those that don’t have entertainment as the primary goal, but rather education, training or awareness. The U.S. Department of Defense was an early adopter of serious games to simulate battlefield scenarios without the cost of physically reenacting battlefield conditions. The government continues to be a prominent developer and consumer of serious games, with a large presence in North Carolina.

“Before I was at ECU I was going to try to come back from California to work at a large game developer in Raleigh. They showed me a game they were developing, and I asked who it was for and they were like, ‘We can’t say,’” Peery said.

Peery is not a game developer by training, at least not the coding side of game development, but his graduate education in English and film gave him entre into the gaming world because he understood how to develop a story and manage complex projects.

“When this job presented itself, they needed someone who could speak to the faculty and understand research and things of that nature,” Peery said. “So that’s where my degree came into place.”

The transition to the development of the Virtual Clinic — the College of Nursing’s home-grown serious game — was an easy fit for Peery. His academic research focuses on the gamification of non-gaming spaces, like online shopping and user experience. Serious games are best suited for the space between a person having no knowledge about a subject and being at a point of mastery of that subject — a broad continuum of experience — and different for every learner.

The students’ needs in this in-between stage are repetition and novelty — experiential models that in the real world are time and cost prohibitive. The requirement for living and breathing simulated patients, and faculty to oversee the learning experience in the real world, is incredibly costly.

In the Virtual Clinic gaming space a nursing or medical student can repeat a simulated office visit as many times as is necessary. Need to ask a patient, for the seventh time, how they are feeling and when their fever started? No problem, just restart the game. Not picking up on the subtle cues that would lead to the diagnosis of a serious medical condition? Hit the replay button.

The serious game framework allows health sciences students the opportunity to use their most valuable healing tool — their minds — as many times as necessary and no one is required multiple, needless needle sticks.

While there are other off-the-shelf games that are used by nursing and medical schools, those games are more a simulation where the player has free rein to perform unnecessary medical procedures. The game developed by Peery and his team at ECU is different because player responses are limited in each situation to achieve structured learning goals rather than a free-for-all gaming experience.

“You could have someone come in with a broken arm and you could give them a colonoscopy — wildly inappropriate and not even necessary — but the commercially available games would allow you to do that,” Peery said. “A serious game is going to limit those choices so the learning is guided rather than just throwing the kitchen sink at you.”

Teaching health sciences students

There are two ways that faculty on the Health Sciences Campus use the Virtual Clinic for education. One technique is for professors to assign students Virtual Clinic scenarios as lessons to work on patient assessment and disease diagnostic skills. The other is to have students build their own cases for others to use, which requires a greater breadth of consideration and deeper research effort.

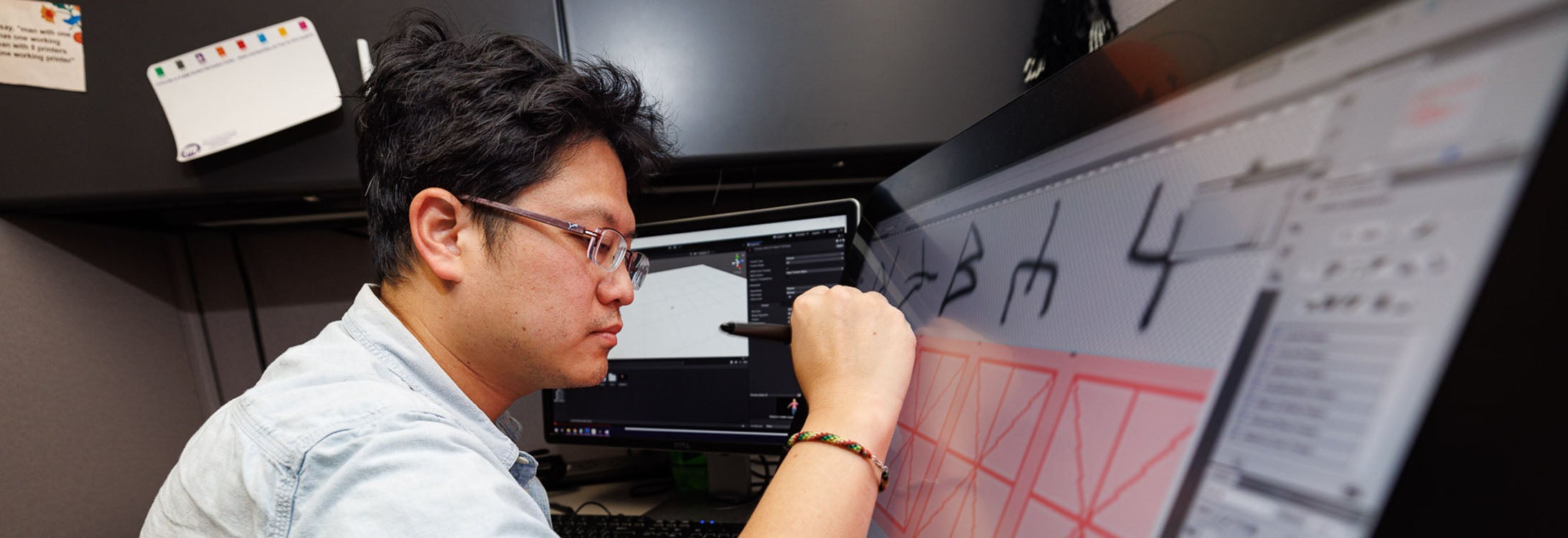

Josh Peery, an instructional technology specialist with the College of Nursing, discusses Kuan-Hun Chen’s graphic work that will be used in an educational project for nursing students.

The research and planning necessary to develop a game scenario is a sneaky way to build analytical dexterity and forces the student to think laterally, which is often missing from the regurgitative style that students often encounter when preparing for an anatomy and physiology test.

When Pamela Reis, the department chair of nursing science and Ph.D. program director, taught an elective course at the Brody School of Medicine she had her medical students work interprofessionally with ECU nursing students to create simulated patient cases that could be included in the Virtual Clinic game. Reis, a senior faculty member at the College of Nursing, who practiced clinically as a nurse midwife and neonatal nurse practitioner, tasked her students with developing the narrative structure for a virtual appointment with a patient. Students had to develop four cases during the course — to come up with realistic maladies affecting a virtual patient, research the symptoms associated with the patient’s complaint and consider the red herring diagnoses that could be offered to a game player.

“Players had to ask the patient certain questions to come up with the correct diagnosis,” Reis said. “They got points deducted if they failed to ask the right questions or ask inappropriate questions. They had to write a SOAP (nursing documentation) note and then were assessed a final grade.”

Reis said building the scenarios requires mental gymnastics of the students, which facilitates learning in a way that simply reading a textbook couldn’t accomplish.

“It’s a good way for students to organize their thoughts without judgment,” Reis said. “The Virtual Clinic is a way to present students with cases that they’ll see in clinical practice in a non-threatening environment, although it is somewhat threatening because the grade is associated with it.”

Lindsey Lang, from Durham, was a registered nurse before being accepted to the Brody School of Medicine. She’s set to graduate in May 2023 and will take her nursing and medical training with her into residency, including the opportunity to build cases for the Virtual Clinic during one of Reis’ elective courses.

“With my nursing background and my medical education background, I built four different cases,” Lang said. “Josh took me through the gaming structure of how to input the information, build the characters and input background information.”

One of the cases Lang built was a simple obstetrics scenario that incorporated questions that a health care provider might ask and corresponding answers that a “patient” might respond with, each with varying levels of realism. Lang values the opportunities that come from a greater acceptance of virtual education tools that she didn’t have earlier in her medical training.

“When I was in nursing school, it was a lot of didactics. We would have some simulations, but now having more simulations is helpful,” Lang said. “One thing COVID has taught us is doing more things virtually has been a benefit to our education.”

Future of serious games

Randy Brown, who recently retired as vice president of Applied Research Associates, an industry leader in entertainment and serious games, said that game development is often limited by the public’s demand for intensive, realistic graphics.

“Students expect games that look somewhat realistic in a lot of instances,” Brown said. “People don’t have Triple-A entertainment budgets for this, they’ve got training budgets and a lot of times that’s the last dollar for organizations.”

Peery, an instructional technology specialist with the College of Nursing, develops the Virtual Clinic serious game for nursing and other health sciences students.

For larger, more graphically intense games, Brown said that a team of at least five to seven people — animators, lighting and script developers, and a project lead — are necessary. But with current advances in game development and recycling of the underlying code, it is feasible for smaller teams to turn out a quality educational game, like the Virtual Clinic.

When education — imparting knowledge rather than driving revenue — is the goal of the game, and graphics are less of a concern, the personnel requirement can shrink.

“If the customer is not so fixated on Triple-A graphics quality, that takes a lot of pressure off. The cost of development is actually dropping because the (graphics) engines are becoming so much easier to use, repurpose, prototype and build on top of,” Brown said. “So, it makes it a team able to create the content.”

Sue Bohle, a former tech journalist and public relations expert, as well as the executive director of the Serious Play conference, believes that the College of Nursing is ahead of the game when compared to institutions of its size.

Bohle said that the fastest growing sector of the serious game market is health care because of the cost savings that come from virtually replicating complex medical scenarios for medical and nursing students.

“Usually, virtual reality programs also have assessment systems that can show when a student is not doing the procedure correctly and guide them to learn,” Bohle said. “They can practice almost as if it’s a virtual quiz where there is no embarrassment.”

The challenge that many medical education institutions have with off the shelf serious games is the need to tailor the existing game to the needs of the students and faculty, which could be more work than help. Sometimes, Bohle said, a well-trained instructional designer can use existing technologies to create a custom-built game from scratch — similar to what Peery has done at the College of Nursing.

“The do-it-yourself, create-it-yourself market is as vibrant as the formal technology environment. Schools do have the tools to do things in house, cheaper,” Bohle said.

Bohle believes serious game development has a bright future, one that even financial analysts are not prepared for.

“The game-based learning industry will surpass the entertainment industry,” Bohle said. “The statistics were in the last report that my analysts did. I took his data to the Wall Street Journal — they just didn’t believe it.”

Peery and his development team have plans to expand the Virtual Clinic game to include professional refresher training and even self-care training and education for patients and non-medical professionals.