RURAL RESEARCH

ECU, ECU Health research focuses on improving rural health

Doctors, nurses, therapists — none can do their clinical jobs without facts: proof, by way of blood tests, X-rays and hands-on observations in order to determine a clear path forward to progress a patient to wellness.

The acute skills of observation and diagnosis are critical for the individual patient, but before health care providers can make clinical judgments and chart a path forward for their patients, health care as a whole needs facts. The facts that systemic health care requires comes in the form of research, which has given us modern medical wonders like antibiotics, MRIs, gene editing and thousands of other discoveries and inventions that have made historical medical death sentences into minor inconveniences.

The tradition of research in the pursuit of making health care better, particularly for those in rural and underserved communities in eastern North Carolina, is alive and well at East Carolina University and ECU Health. Here are a few examples of how Pirate researchers are improving lives one study at a time.

Women living with HIV

Dr. Courtney Caiola, an assistant professor at ECU’s College of Nursing and researcher focusing on women and HIV, said that that the HIV epidemic has made an insidious shift, from largely affecting urban populations in the epidemic’s early days to now having taken root in rural and underserved regions — eastern North Carolina has become a ready refuge for the disease.

The National Institute of Nursing Research has funded one of Caiola’s research projects that aims to find out how best to communicate with women living with HIV in rural settings, particularly for those without reliable access to high-speed internet connectivity.

Caiola is fighting an uphill battle, one complicated with social mores and community stigma for residents of rural and underserved area who are diagnosed with HIV.

“The epidemic has changed over the years, in good ways,” Caiola said. “People living with HIV are living really well now, but women living with HIV in the South have some of the highest rates of HIV infection but the lowest rates of viral suppression, which means that that they’re not engaged in care.”

Cultural barriers and social stigma often prevent many women in the South from seeking care, Caiola said. Women in a more urban setting might be able to visit an HIV clinic with little fear of disclosing her HIV status, but that isn’t necessarily the case when community members know which clinics serve patients living with HIV.

Caiola’s research partners well with an outreach and research project spearheaded by Dr. Leigh Atherton, an associate professor in the Department of Addictions and Rehabilitation Studies at ECU’s College of Allied Health Sciences.

Atherton endeavors to find ways to prevent the spread of HIV in rural North Carolina by encouraging those in high-risk substance use groups to seek treatment for their addictions. Atherton’s team partners with community-based HIV outreach groups and supplements testing supplies, which puts his counselors in direct contact with at-risk populations.

One of the highest hurdles to clear for researchers focused of HIV treatment and prevention in North Carolina is simply getting enough people to participate in the research.

“There’s something called courtesy stigma. A lot of women with HIV are mothers and they don’t want the stigma that they might experience to be passed on to their kids, so they tend to keep very low profiles and be a bit socially isolated,” Caiola said, which necessitated her team partnering with multiple other HIV researchers in North Carolina and across the South.

Initial research findings suggest there is no one-size-fits-all solution to communicating with HIV positive women in rural areas.

“As clinicians, the differences in the way people respond to their circumstances is often very clear, but in research, people are often grouped into broad demographic groups for the sake of generalizability,” Ciaola said. “In fact, two women with similar demographic profiles, like Black women living with HIV in a rural area, may have wildly different responses to dealing with HIV.”

Disease prevention

For Brody School of Medicine Drs. Greg Kearney and Doyle ‘Skip’ Cummings, health-related research orbits around overarching conditions that spiderweb across the body creating a cascade of adverse consequences — hypertension and environmental public health.

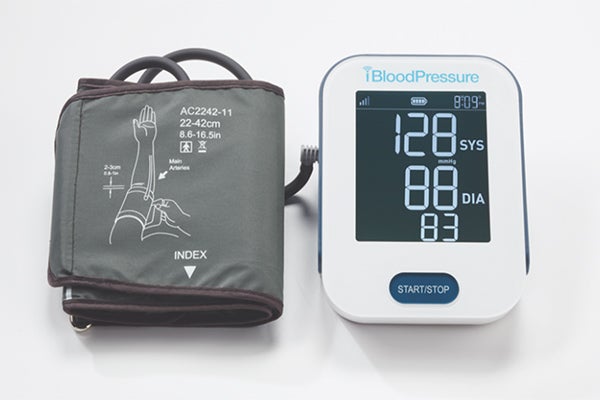

In order to find ways to address the high levels of hypertension in rural areas, Cummings is piloting a program, in collaboration with UNC-Chapel Hill and the University of Alabama, to test home health reporting technologies that can identify high blood pressure patterns and upload those readings into a computer system for a team of health care providers to evaluate.

“Instead of just one provider seeing a patient every three months or so in the office, we’ve got a team of people that are trying to stay on top of blood pressure values and recognize when a patient’s blood pressure patterns appear to be out of control, signaling the need for quick follow up, often by telephone or telehealth,” Cummings said.

An example of the cellular blood pressure cuff being tested by ECU researcher Dr. Doyle “Skip” Cummings. (Contributed photo)

In setting patients up with the telehealth devices being tested, researchers are using the in-person meetings as an opportunity to gather baseline information that can be used to identify some of the causes of hypertension in disadvantaged and rural communities.

“We’re using screening instruments during the baseline visit to look at the social determinants of health — food insecurities and transportation and housing instability,” among other data points, Cummings said.

Cummings, a Brody professor of public health and the Berbecker Distinguished Professor of Rural Medicine, said that the amount of data that the system transmits from a patient’s home to the central computer is so small that the team has had no problems thus far with getting data to the health care team.

“I just came back from two days of site visits out in the mountains in rural North Carolina and we took the blood pressure cuff with us,” Cummings said. “We drove all over the mountainous areas and tried the blood pressure cuff in multiple places, and we didn’t have any problems. Part of it is because that blood pressure value is a very small amount of data. It’s not like you’re sending a video or pictures.”

Kearney’s research is rooted in a desire to understand environmental and occupational impacts on human health, particularly asthma and the effects of chemicals and pesticides on farm workers.

Kearney, an associate professor of public health at Brody and founding director of the school’s Environmental and Occupational Health Program, is working with a toxicology researcher at UNC-Charlotte, who has developed a portable medical device that can be used to test for pesticides in human blood.

Kearney said that they have pilot tested the device with farm workers working with different crops.

“Because of the nature of their work, they are in the fields daily during the season, and are at high risk for exposure to pesticides,” Kearney said. “Some pesticides are quickly metabolized in the body’s systems, so a person who is exposed and located in a rural area may have difficulty getting tested right away. With a simple finger stick and a drop of blood, this device can quickly alert you to pesticide exposure.”

Last year, Kearney organized a team and worked with community partners to conduct a regional community health needs assessment for the eastern part of the state. The project included working with representatives across 33 mostly rural North Carolina County health departments and ECU Health.

This research is critical for not-for-profit hospitals, which are required by law to complete community health needs assessments every three years, to understand how to plan for health care investment.

“The community health needs assessment and outcomes is a very serious process,” Kearney said. “It provides a mechanism for hospitals and communities to come together and decide how to invest funding with community-based organizations to address the most pressing health care related problems in their communities.”

Fresh start

In eastern North Carolina, people with Type 2 diabetes are twice as likely to die as the rest of the state and the country.

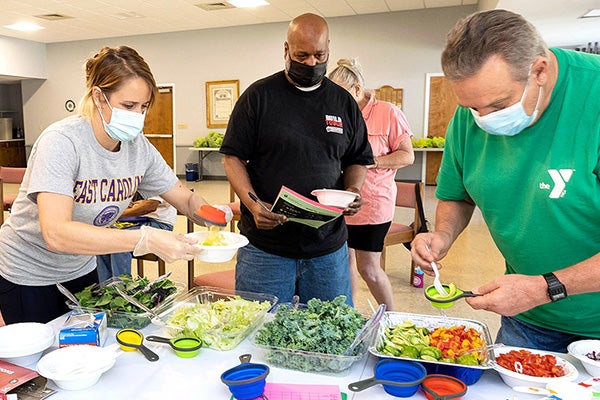

Fresh Start, a research and outreach project established by Dr. Lauren Sastre, associate professor of nutrition science at the College of Allied Health Sciences, partners with free clinic members of the North Carolina Association of Free and Charitable Clinics across 11 counties in eastern North Carolina. The research and outreach program aims to prove is that diabetes can be controlled by layering previously disparate approaches to diabetes management — providing healthy food to those in need, teaching patients how to incorporate food and exercise into their lives and building accountability structures.

“I’m from North Carolina, and I don’t want to keep seeing that we have diabetes in this region that is out of control,” Sastre said. “There are problems that are hard to solve and this one isn’t hard to solve — it’s just whether or not we are actually going to do it.”

The Fresh Start program provides healthy foods to those in need, teaching patients to incorporate food and exercise into their lives. (ECU photo by Rhett Butler)

Sastre and her expansive interdisciplinary team of dozens of ECU students, trainers and researchers hope that through teaching patients healthy ways to cook and how to put structures for accountability in place, the Fresh Start program could help patients learn to more effectively manage their disease.

“The question we asked ourselves was, ‘Can these things that other people have done individually, that have shown some effect, complement each other and should the synergy be more impactful?’” Sastre said. “It turned out to be what we hoped it would be.”

The first challenge, exposed early in the research process, was to get to diabetes patients where they were. Sastre’s team found, through face-to-face engagement with patients, that many in rural communities have a very real lack of digital connectivity.

“Everything is done over the phone with health coaching, and we’ve even moved in-person classes to the evenings,” Sastre said. “A lot of our folks are considered the working poor and they make just enough to not have a lot of help and they can’t go to classes in the morning or afternoon.”

Sarah Elliott, a junior studying nutrition science and a Fresh Start volunteer, was heartened by the progress that her patients made.

“We have received really positive patient feedback from the group classes and the health coach experience. People are saying, ‘Not even my own family care as much about my health as my health coach did,’” Elliott said. “It has been impactful to see the difference that this is making in people’s lives.”

And what does the initial research of this integrated approach to diabetes management show?

A1C, one of the blood markers of the body’s control of blood sugar, will typically go down one to one and a half percent with Metformin, which is the standard medication that diabetics are put on initially. The Fresh Start program’s mean decline in just four months was 1.87%, which is significant accomplishment that Sastre credits to the program’s multi-layered approach to food and lifestyle management.

“The patients enrolled in our program, their blood sugar control improved for some almost double what it could with some medications,” Sastre said. “Our patients also had reduced hospital re-admission rates, so we know that the program is working. It’s addressing diabetes and improving quality of life. It’s making an impact on disparity.”

Brandon Stroud, a doctoral student, knows farming in eastern North Carolina. He grew up on a farm near Dunn and his grandfather worked several hundred acres of land close to where Stroud was raised.

Undergraduate students, Stroud said, are taught in classrooms the skills they will need to be effective in a hospital setting. Research skills students learn working with patients in the Fresh Start program helps them to evaluate the effectiveness of integrating the three pillars of the program, which makes book learning real.

“This is different than lab-based research,” Stroud said. “It’s community-engaged research, right? So, you’re working with many different partners out in the community — clinics, farmers and different organizations. It teaches us the life skills that we need to be beneficial moving forward whether we want to go into business or continue down a clinical route. The research validates our personal experiences when we are able to employ rigorous evaluation and report these meaningful outcomes.”