ECU researcher brings problem gambling to light

Research by an East Carolina University professor shows that North Carolina has a high rate of problem gambling despite the lack of legalized gambling available in the state, said Dr. Michelle Malkin, assistant professor of criminal justice in the Thomas Harriot College of Arts and Sciences.

Problem gambling not only affects the gambler; an estimated 10 to 17 people, primarily family members or coworkers, are affected by a gambler’s addiction, Malkin said.

Dr. Michelle Malkin, assistant professor of criminal justice, is researching problem gambling and its effect on gambler and their families. (Photo by Cliff Hollis)

“(Problem) gambling produces a cycle of addiction wherein gamblers acquire debt from gambling and must then gamble to earn money to pay off these debts while remaining stuck in this pattern and unable to desist, resulting in gambling-motivated crimes,” she said.

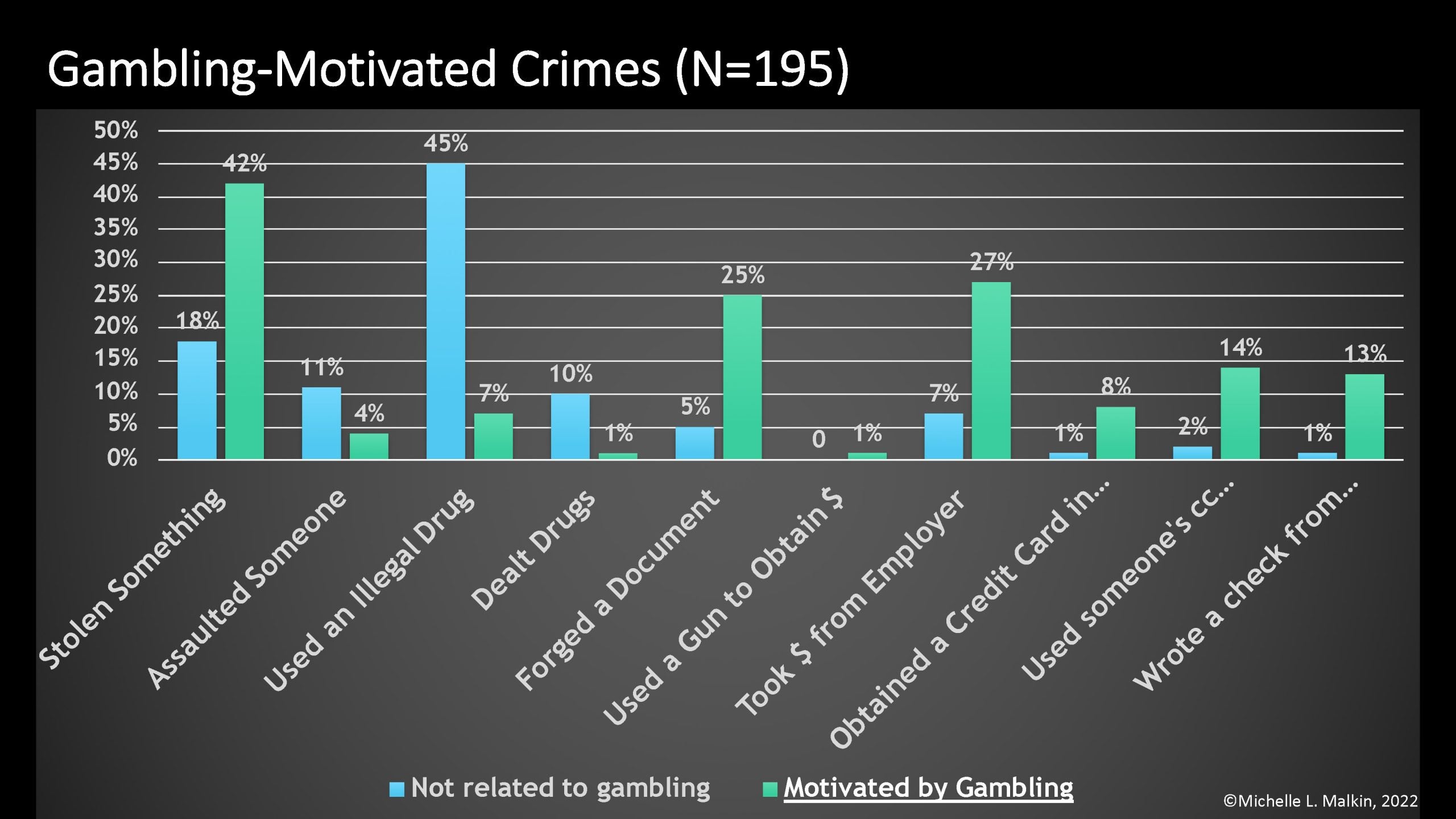

According to Malkin, gambling-motivated crimes are primarily non-violent, financial offenses committed to pay off gambling debts or continue gambling. The most common types of gambling-motivated crimes are embezzlement, larceny, theft, robbery and forgery or creating counterfeit money, and these are most often committed against family, friends or employers.

“The more severe the addiction, the more likely the individual will commit a gambling motivated crime,” she said.

Malkin is fast becoming a nationally recognized expert in the field of problem or disorder gambling, with a focus on gambling-motivated crime. In the past three years, she has been an invited presenter or keynote speaker at 10 conferences and symposiums on the subject — five just this year.

Malkin’s newest article, which is out for consideration for publication, is “Gambling-Motivated Crime: The Social, Economic and Criminal Consequences of Problem Gambling.”

Through her research and various presentations, Malkin explains the history of gambling, differences between social gambling and problem gambling, how problem gambling may lead to specific crimes to supplement the gambler’s addiction, consequences or lack thereof for these crimes, and statistics and differences among problem gamblers based on gender.

“It is estimated that a problem gambler affects the lives of between 10 to 17 individuals, primarily within the family and work environments,” Malkin said. “Issues within the family include high divorce rates, child neglect, child abuse, family dysfunction and a possible increase in intimate partner violence.”

Based on Malkin’s research, rates of problem gambling throughout the U.S. range from 1% to more than 8%. North Carolina has a 5.5% rate of problem gambling, which she said is high “given that people within N.C. do not have easy access to many forms of gambling that are currently legalized elsewhere.”

She said this percentage would likely have increased, even among college-age individuals, if legalized sports betting was passed in North Carolina this summer. However, the bill did not pass, and currently, sports betting is only legal at the two Cherokee tribal casinos in the western part of the state.

Malkin said that nationwide, 50% of individuals at the “most severe stages of problem gambling” are likely to commit a gambling-motivated crime, though most do not face any type of legal penalty or sanction. The crimes most likely to be penalized and lead to conviction are embezzlement and opening a credit card in someone else’s name.

Crimes perpetrated by a problem gambler may also be seen as an alternative to suicide, according to Malkin. Her research indicates 20% of problem gamblers will attempt suicide — the highest percentage of all addictions.

Research shows that theft, document forging and embezzlement are the top forms of gambling-motived crimes. (Contributed graphic)

“Gambling issues can be hugely detrimental to individuals, their families and their communities,” she said. “Individuals face substantial social, economic, legal and employment issues that often result in loss of income, loss of assets, and overall broken relationships and families.”

Within the criminal justice system, Malkin sees several issues related to problem gamblers. For example, she says the courts do not often understand problem gambling or assess for gambling problems; gambling addiction is not treated like other addictions; there is a lack of programming or treatment for problem gamblers; and correctional personnel are not trained to handle gambling issues or individuals who may become problem gamblers while in prison.

She suggests potential resources for gamblers include Gamblers Anonymous, inpatient and outpatient therapy, Zoom meetings and social media support pages — especially during the COVID pandemic — including Women Gamblers in Recovery, Gambling Addiction and Recovery, and Problem Gambling Hope & Recovery Facebook pages, and the National Council on Problem Gambling website or its helpline at 1-800-522-4700.

Malkin’s current project on problem gambling involves collecting data from the Clark County, Nevada, gambling treatment diversion court — the only gambling diversion court in the United States — where treatment, instead of incarceration, is made available for nonviolent offenders.

Through her research, Malkin is evaluating the court to learn best practices and areas for improvement, so that other jurisdictions interested in starting similar programs will have up-to-date best practices. Malkin hopes to create a handbook for those interested in starting gambling treatment diversion courts. Ohio, New Jersey and Rhode Island are looking into establishing similar specialty courts.

“My hope is for problem gamblers accused of gambling-motivated crimes to have the same court diversion programs as other people who commit crimes motivated by their addictions, similar to the more than 3,500 drug courts that keep people with drug additions out of prison and instead focus on their recovery,” Malkin said. “Once you get someone help from their addiction, their likelihood to recidivate — or commit another crime — practically diminishes.”