FORGOTTEN WWII BATTLE

ECU researchers receive NOAA grant to explore WWII battle site in Alaska

Researchers in East Carolina University’s Program in Maritime Studies have received a $707,000 grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Office of Ocean Exploration and Research to explore a World War II battle site in Alaska.

The project, “Exploring Attu’s Underwater Battlefield and Offshore Environment,” will be led by Dominic Bush, a doctoral student in the coastal resource management program within ECU Integrated Coastal Programs, and Dr. Jason Raupp, assistant professor of maritime studies in the Thomas Harriot College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of History.

This interdisciplinary project will survey the seabed surrounding the Alaskan island of Attu to document underwater cultural heritage associated with the battle that took place May 11-30, 1943.

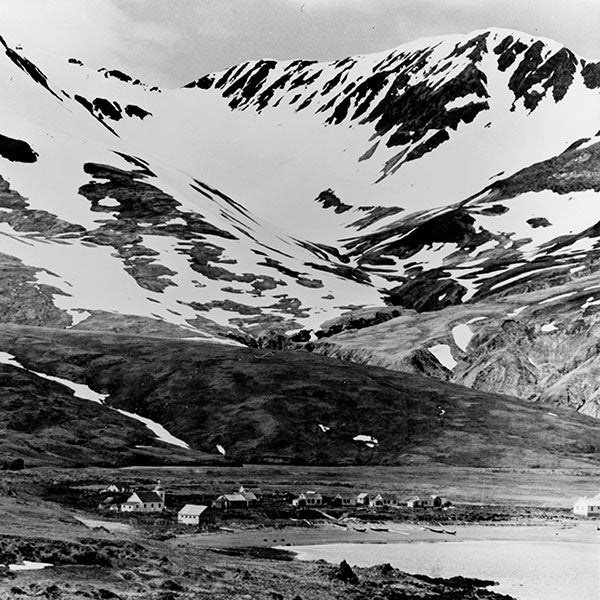

The Alaskan island of Attu is home to the only WWII battle fought on North American soil.

Bush first became interested in the history of Attu during a spring 2020 battlefield archaeology class led by Dr. Jennifer McKinnon, assistant professor of history and maritime studies, who encouraged Bush to apply for the grant to further his research.

“My interest in the Aleutians stems from the fact that I, myself, am part Native Aleut, as my maternal grandmother is the daughter of a full-blooded Chugach woman and a Danish sailor,” Bush said. “I’ve been aware of my Aleutian heritage my entire life but was never told much about it. As the pandemic shut down everything, I decided to completely dedicate myself to this class assignment and learn everything I possibly could about the main WWII conflict in the Aleutians: the Battle of Attu.”

Bush said the three weeks of combat by land, sea and air at Attu resulted in the loss of nearly 600 U.S. service members, with an additional 3,000 injured. The entire 2,500-person Japanese garrison, apart from 29 prisoners of war, perished during the battle.

“In June 1942, in a move coordinated with the Battle of Midway, the Japanese military took over Attu and nearby Kiska,” Bush said. “The exact motivation for the invasion of these two Aleutian Islands remains a topic of debate, with historians speculating that it was either a distraction from Midway, an attempt to provide northern flank protection for the Japanese naval fleet approaching Midway, or an effort to establish air bases to either attack mainland Alaska and the West Coast or prevent a northern U.S. invasion of Japan.

“Whatever the rationale, the move had the psychological benefit of Japan being able to say they now occupy U.S. soil in North America, a feat that had not been done since the War of 1812. The Unangan on Attu were shipped to Japan as prisoners of war, and although they were allowed to return to the U.S. in 1945, they were barred from ever returning to their home island.”

Field research for the project will occur in the summer of 2023 and utilize advanced marine survey technologies to document the cold-water marine environment, and locate and record the remains of ships, aircraft and other military vehicles lost during the battle. This research may provide a foundation for further work to locate missing-in-action service personnel.

“Being both the westernmost part of North America and the largest uninhabited island in the U.S., Attu presents an exciting but logistically challenging opportunity for research,” Raupp said. “Despite the battlefield’s recent incorporation into the Aleutian Islands WWII National Monument, it remains relatively unknown to the American public and is referred to as the ‘Forgotten Battle.’”

The Attu battlefield is often called the ‘Forgotten Battle.”

According to Bush and Raupp, while some of the battle’s remains on the island have been documented, Attu’s underwater battlefield has been completely ignored.

“The waters around Attu likely contain a large amount of submerged cultural heritage related to the conflict,” Bush said. “According to archival research, this could include up to 10 U.S. aircraft, nine Japanese aircraft, nine U.S. landing craft, three Japanese ships and numerous smaller barges and other watercraft.

“Together, these sunken vessels represent a yearlong occupation of Attu and the attempts by the U.S. military to remove the foreign force. The battle’s maritime component is highlighted by the fact that it was the first amphibious invasion completed by the U.S. Army and only the third assault of this kind by the U.S. during WWII. Lessons learned from the Attu campaign were instrumental in forming mission plans for the subsequent island-hopping campaign that eventually led to the Allied victory in the Pacific.”

The research team seeks to bring together indigenous Alaskan history experts, maritime archaeologists, marine biologists and innovators in remote sensing technology to better understand the cultural and natural landscape of the waters around Attu.

In collaboration with ECU researchers, the team will consist of co-investigator Dr. Caroline Funk of the State University of New York at Buffalo, who is among the world’s foremost authorities on Attu’s indigenous history. Dr. Rhian Waller of the University of Gothenbur, in Sweden, has more than two decades of experience in researching marine invertebrates and will serve as the project’s lead biologist. Steven Link and Christian Clark of ThayerMahan, Inc., a marine technology company that specializes in developing autonomous vehicles for underwater remote sensing surveys, will conduct survey operations using a towed system and an autonomous vehicle. Japanese underwater archaeologist Dr. Kota Yamafune of A.P.P.A.R.A.T.U.S. LLC will supplement the sonar operations with underwater photography and videography surveys.

“To bring attention to this chapter in U.S. history, the research team will inventory Attu’s maritime heritage sites to produce high resolution maps of the seafloor and detect potential targets. A remotely operated vehicle (ROV) will be used to capture follow-up video and still photographs,” Bush said.

According to Bush, the team also will look for evidence of pre-WWII human activities, as Attu’s indigenous occupation of the island dates from more than 4,000 years ago until the Japanese invasion in 1942.

To aid this effort, Bush said researchers will be joined by Native Unangan (Aleutian) consultants who will bring invaluable cultural perspective to the understanding of Attu’s marine environment and history.

“Finally, the optical imagery produced by the ROV will not only aid in identifying submerged cultural heritage, but it will also analyze and examine the cold-water coral and sponge communities that may be growing on the wreck sites,” Bush said. “These invertebrates constitute keystone species and often function as habitats for important marine animals.”