KEEPING FARMWORKERS HEALTHY

Online course guides physicians on treating toxic exposures farmworkers might encounter

Farmworkers encounter numerous toxic substances, whether from synthetic or natural sources. That’s why the Eastern Area Health Education Center is offering a continuing education program titled, “Farm Toxicology for Primary Care: Recognition and Management of Pesticide Poisonings.”

The eight-module program is a self-paced, online curriculum that covers exposures to insecticides, herbicides, rodenticides, fungicides and poisonous gases, as well as short- and long-term consequences of those exposures for farm workers.

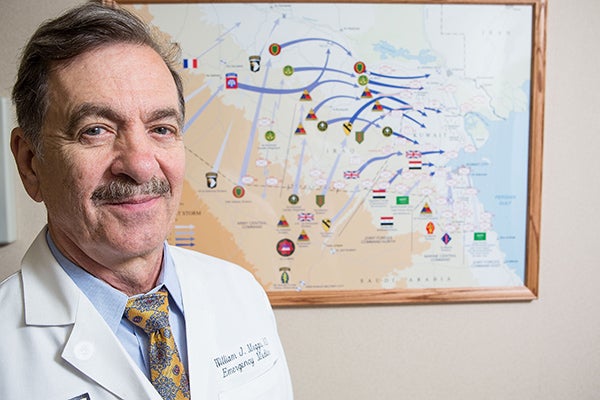

Dr. William J. Meggs, professor of emergency medicine at the Brody School of Medicine, is one of the presenters participating in the online program. (ECU file photo)

Physician presenters represent a broad health background:

- William J. Meggs, professor of emergency medicine at the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University and a board-certified toxicologist.

- Jason B. Hack, professor of emergency medicine at the Brody School of Medicine and a board-certified toxicologist.

- Jennifer Parker-Cote, associate professor of emergency medicine and medical toxicologist at the Brody School of Medicine.

- Ricky Langley, adjunct associate professor of public health at the Brody School of Medicine.

- Dalia Alwasiyah, emergency medicine consultant and medical toxicology consultant from Charlotte.

- Stephanie T. Weiss, board-certified medical toxicologist and formerly senior addiction medicine research fellow at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine.

- H. Thomas Cusick III, occupational and environmental medicine specialist at Duke University.

- Gayle Thomas, medical director of the N.C. Farmworker Health Program and associate professor of family medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

This is the third iteration of the program. The first was about 15 years ago, said Robin Tutor Marcom, director of the N.C. Agromedicine Institute, based at ECU. Earlier versions focused solely on pesticides. More recently, Meggs added sections on other areas of concern, such as animal bites and stings, plant toxicity and heat illness.

On farms, not all chemical exposures are from pesticides. For example, anhydrous ammonia is a gas used as a fertilizer; it can cause burns. Decomposing manure gives off hydrogen sulfide, which can cause heart arrhythmias. Engines emit carbon monoxide.

“There are a lot more toxins on the farm than just pesticides,” Meggs said. “And a lot more illnesses.” And illicit drug use, he added.

“Many physicians haven’t been taught to take an occupational and environmental history,” he said. “As health care providers, we need to have open minds and consider all the possibilities” for why a person might be ill.

Robin Tutor Marcom, right, director of the N.C. Agromedicine Institute, speaks to then President of the University of North Carolina System Margaret Spellings in 2016. The toxicology program was first offered nearly 15 years ago. (ECU file photo)

“That is agromedicine 101, which leads to someone not being diagnosed at all or misdiagnosed,” Tutor Marcom added about the lack of occupational and environmental histories. “It does seem basic, but it doesn’t happen.”

She has worked in migrant health for more than 20 years and grew up in a farm family.

“Agricultural medicine is a much bigger field because of all the exposures,” she said, adding the course is unique and is included in the University of California-Davis’ Pesticide Education Resources Collaborative, or PERCMED.

“A few years ago, I spoke with a physician who worked with migrant farm workers,” Tutor Marcom said. “She told me, ‘You know, they should just do away with all the pesticides they use in farming.’”

But that’s not a realistic approach, Tutor Marcom said. “Soil and plants have diseases and pests, just like people,” she said. “The chemicals are needed. If we take away this formulary that farmers have, they’re not going to be able to produce the food to feed the U.S. and the rest of the world.”

And not all pesticides are highly toxic to humans. Hack points out that pyrethroids, nicotine and neonicotinoids, for example are natural or derived from natural sources and are highly effective for controlling insects but have relatively low human toxicity, with certain exceptions.

And it’s not just farm owners and farm workers who might be exposed to agricultural chemicals. Home gardeners use them; homeowners use bug sprays and rodent baits.

“What we’re trying to do is increase (physicians’) awareness and give them the tools they need,” Tutor Marcom said. “Our job is to say, ‘Let’s do it safely and responsibly.’”