ECU researcher lands licensing agreement for patent to treat Restless Legs Syndrome

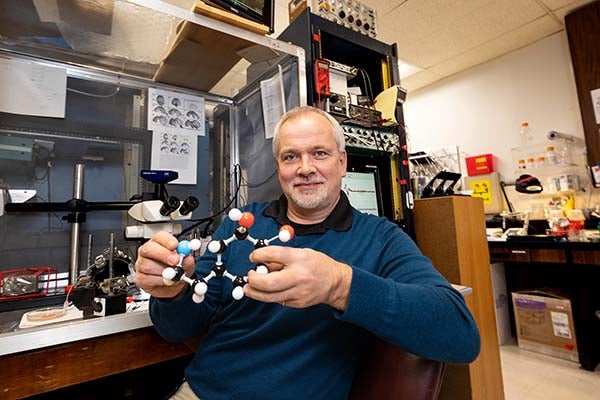

Dr. Stefan Clemens, a professor in the Brody School of Medicine’s Department of Physiology, credits his discovery of a potential treatment for restless legs syndrome (RLS) to “a bit of happenstance.”

Less than eight years later, however, that discovery has helped Clemens secure both a patent and a licensing agreement with the Illinois-based biopharmaceutical company Emalex Biosciences that could improve the quality of life for patients suffering from RLS and other nervous disorders.

Dr. Stefan Clemens, associate professor in the Brody School of Medicine’s Department of Physiology, has discovered a potential treatment for Restless Legs Syndrome. (Photos by Rhett Butler)

Restless Legs Syndrome, also referred to as Willis-Ekbom Disease, is a neurological sensory disorder that causes uncomfortable sensations in the legs and an irresistible urge to move them. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke estimates that up to 10 percent of the U.S. population may have RLS, which occurs in both men and women and can begin at any age, but it typically impacts people who are middle-aged or older more severely.

The disorder is usually treated with dopaminergic drugs, which replace or prevent the loss of dopamine. However, these medications are highly effective initially but lose their effectiveness over time. Patients taking these dopaminergics eventually develop a side effect called augmentation that sees their symptoms get worse, Clemens said.

Clemens was investigating role of the dopamine receptor D3 in animal models with RLS — because that receptor has a suppressive effect in the nervous system — when he discovered that there was an increase in the different dopamine subtype, D1, in these models.

“We asked ourselves, ‘Is this perhaps — at the spinal cord level — an association that might underlie the mechanisms of those changes in the clinical treatments?’” Clemens said. “And then we thought, ‘If we have an upregulation of one receptor, can we selectively block it and see what happens? Can we restore normal behavior?’ And that is what we did.”

This work led to Clemens being awarded a grant from the North Carolina Biotechnology Center to run a small clinical pilot study with a collaborator from the University of Houston using this new treatment method. His teams also began working to see if a medication used to treat Tourette syndrome — a nervous system disorder involving repetitive movements or unwanted sounds — could also have therapeutic advantages for patients with RLS.

“Until now, this medication was only used in clinical trials to treat a motor disorder. It was never considered, perhaps, to also be effective for a sensory disorder,” Clemens said.

The initial basic science findings led ECU’s Office of Innovation and New Ventures team to recommend that Clemens secure a patent for this potential treatment of RLS, and then helped him secure that patent and an eventual licensing agreement with Emalex Biosciences.

“If the (Office of Innovation and New Ventures) had not gotten involved, it would have just been another publication or two on my resume. And that’s it,” Clemens said. “There would not be a new possible drug treatment, so I can’t emphasize their input highly enough. That’s clearly all because of them.”

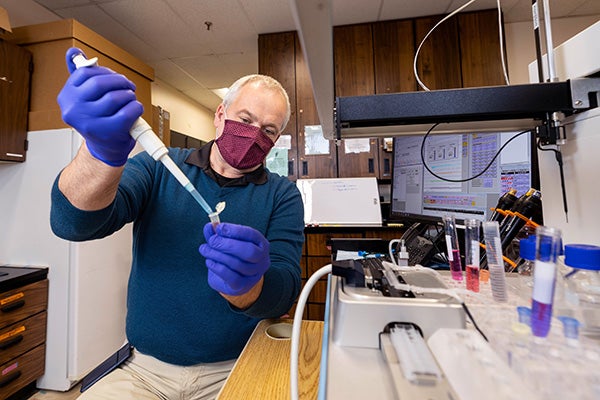

Clemens has secured a patent and licensing agreement with a pharmaceutical company for a potential treatment that could help people with nervous disorders.

The partnership between that office and Clemens also provided Emalex with another potential use for its D1 receptor antagonist, ecopipam. The company was already evaluating ecopipam for the treatment of Tourette syndrome in pediatric patients and childhood-onset fluency disorder (stuttering) in adults.

“This licensing agreement provides Emalex with an expansion of its platform to address an unmet need for those living with RLSa, which currently does not have a U.S. Food & Drug Administration-approved treatment,” said Atul Mahableshwarkar, Emalex’s chief medical officer and senior vice president of drug development said in a release announcing the licensing agreement. “We look forward to evaluating ecopipam to determine if it can provide much needed relief for those whose quality of life and sleep, are impacted by this condition.”

The licensing agreement is another milestone for ECU’s already strong, but growing, reputation in research.

According to Marti Van Scott, ECU’s Director of Licensing and Commercialization, ECU has had more than 50 U.S. patents issued in the last 10 years, including 20 in the last two years. These patents provide the licensees a period of exclusivity so they can develop and market solutions to important social problems, like new therapeutics and medical devices to improve human health.

“I find it exciting to see more of our research community embracing the power of translating their work into new products and businesses for the benefit of society. This culture of innovation is spreading among our faculty, students and regional community and it is showing up in the form of new product and venture development opportunities,” Van Scott said. “This evolution is showing up in many diverse disciplines, including those in physical, life and social sciences, engineering, medicine, art, music, education and more. The sky is the limit for ECU’s innovation ecosystem.”

Dr. Michael Van Scott, interim vice chancellor of ECU’s Division of Research, Economic Development and Engagement, added that Clemens’ research helped the university continue to find new and useful ways to address complex issues.

“When a university or academic team is awarded a patent, it demonstrates that the environment and discovery processes generate new ways of addressing problems,” he said. “It documents the breadth of academic activities, from conveying foundational knowledge to applying knowledge for positive impact in people’s lives and society.”