ECU medical school alumnus writes book on importance of advocacy in medicine

When Dr. Benjamin Gilmer reported to his new job as a rural physician in western North Carolina, he learned he had the same last name as the physician he was replacing.

From there, the story shifted from coincidence to saga.

The 2006 graduate of the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University has written a book about his personal experience transforming from physician to advocate for social justice, mass incarceration and mental illness.

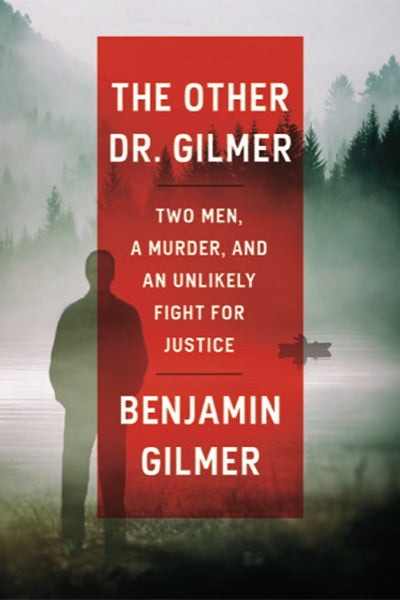

Dr. Benjamin Gilmer, a 2006 graduate of the Brody School of Medicine, released his book on his journey of social justice advocacy, “The Other Dr. Gilmer,” this month through Penguin Random House. (Contributed photo)

Gilmer’s book, “The Other Dr. Gilmer: Two Men, a Murder and an Unlikely Fight for Justice,” published by Penguin Random House earlier this month, chronicles a case of medical mystery, murder and social justice that was featured on NPR’s “This American Life” in 2013 and is now being produced as a motion picture. The story began when Gilmer got a job as a rural physician near Asheville, replacing Dr. Vince Gilmer — the two are not related — after the latter doctor went to prison for killing his father.

What followed is a search for social justice for prison inmates living with mental illness in a system where it is not easily understood or considered.

Benjamin Gilmer returned to Brody on March 11 to discuss the book and his experience as a physician and social justice advocate.

“I’m a family medicine doctor, and I wanted to share that one really important part of what we do as physicians, especially family medicine physicians, is to advocate,” Gilmer said in an interview before his visit. “That’s the biggest thing I want to leave for students: that it’s OK to jump into a journey you may never have known before.”

Gilmer, who is also an associate professor at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and Mountain Area Health Education Center’s (MAHEC) Family Medicine Residency program, realized he needed to write the book in 2017, after then-Gov. Terry McAuliffe denied a clemency petition for Vince Gilmer, who had been sentenced to life in prison.

The other Dr. Gilmer

Vince Gilmer practiced medicine at Cane Creek Family Health Center until June 2004. He was convicted of strangling his father with a rope; he then cut off his fingers and left the body on the side of a road in Virginia. Vince Gilmer returned to the clinic and practiced medicine for several days until he was arrested for murder.

When Benjamin Gilmer joined the clinic, patients told the new doctor that Vince Gilmer had been a great doctor and person. Equipped with curiosity and questions, Benjamin Gilmer began visiting Vince Gilmer in prison and became convinced that his predecessor suffered from serious mental health issues that were not recognized by or addressed by the prison officials. Through trial transcripts, Benjamin Gilmer understood that the murder trial hinged on the belief that Vince Gilmer used his medical expertise to fake mental illness. Upon further investigation, Benjamin Gilmer developed the belief that various conditions lent to his predecessor’s mental state, including Huntington’s Disease, an inherited disease that can cause bizarre or unusual behavior.

“The Other Dr. Gilmer” by Dr. Benjamin Gilmer chronicles his experience of becoming an advocate for those facing social injustice, mass incarceration and mental illness. (Contributed photo)

From there, Benjamin Gilmer’s passion for justice grew until he was compelled to find time to write the book, hoping to change McAuliffe’s mind before he left office in 2018.

Gilmer got up at 4 or 5 a.m. to write, after which he would care for patients and then continue working on the book.

“I sort of saw myself as a student of writing throughout this process,” he said.

The intersection of mass incarceration and mental illness became a sticking point for Gilmer.

“How could I not know as a physician how stratospherically horrific this problem is?” he said. “I felt like I was called upon to learn about it and do something about it.”

Gilmer teared up as he shared the story with an in-person and virtual audience on March 11. He pointed out that students in the audience and who read the book can use its lessons for a variety of careers, from law to public health.

“The other concept I want to leave for students is that medicine is not just an intellectual profession or process,” he said. “In order to be drawn toward things you are emotionally attached to or inspired to do something about, you have to live with an open heart, expose yourself, make yourself vulnerable — and those are things we don’t learn as students.”

From student to advocate

Gilmer is an international Albert Schweitzer Fellow and attended Davidson College followed by medical studies at the Sorbonne in Paris, France and at Brody. While earning his medical degree, his Schweitzer Fellowship led him to Africa and Ecuador, where he gained a worldly perspective on health disparities and inequity. Those experiences contributed to his penchant for advocacy.

“Physicians can be — we have to be — advocates,” he said. “Our realm of influence can be much larger than we imagined.”

As the medical director for MAHEC’s Rural Health Initiative and Rural Fellowship, Gilmer is still passionate about advocating for global and rural health disparities. He has worked extensively in Central and South America and West Africa. He also inspires students to pursue rural health.

Gilmer said his fellowship experience led him to live out Albert Schweitzer’s mantra of “reverence for life,” a belief that he shares with his mentor at Brody and beyond, Dr. Tom Irons, ECU’s associate vice chancellor for health sciences and a professor of pediatrics.“We share a passion for the principles that Dr. Schweitzer practiced and lived,” Irons said of Gilmer during his introduction.

Gilmer said his experiences at Brody and in eastern North Carolina gave him a deep understanding of disparities and equities in medicine, which also shines through in the book.

“It’s a special opportunity to practice rural medicine,” he said. “It doesn’t matter where you live or what community you practice in. There is always justice to be tapped into. The need is always certainly greatest in rural spaces; this is where people suffer the most. The most powerful advocates should be the rural providers.”

Gilmer’s advocacy might have made a difference.

On Jan. 13, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam — who had read “The Other Dr. Gilmer” — pardoned Vince Gilmer so that he could be released from prison. When the pardon came down, Vince Gilmer was 59 years old and had been incarcerated for 17 years.

While writing the book and discussing the case with various audiences has been an unexpected yet rewarding journey for Benjamin Gilmer, his trip to Brody to share the story brought him back to some of his earliest realizations of who he would become as a doctor.

“It’s always exciting for me to speak to students; it’s such a formative time in their lives when they identify or preserve their ideals,” he said. “So much about studying medicine either beats the ideals out of you or consolidates them and makes them stronger. I want to use this book as a tool to help protect their idealism and help strengthen their focus about the importance of pursuing advocacy work and social justice in medicine — to make sure it’s on their radar and to encourage them to be bold.”