SUNKEN HISTORY

Decade-long project documents WWII wrecks off N.C. coast

It’s no secret that hundreds, if not thousands, of ships and their crews have met their fate off the coast of North Carolina; the area is known, after all, as the Graveyard of the Atlantic. But few realize just how many of those ships were lost not to storms or sandbars, but in battle during World War II.

Over the last decade and more, a collaborative effort involving the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries has identified, surveyed and documented the location and condition of more than 50 wrecks associated with the German effort to disrupt Allied war supply lines. East Carolina University and its faculty, staff, students and alumni have played key roles in the project, which led to the recent publication of Battle of the Atlantic: A Catalog of Shipwrecks off North Carolina’s Coast from the Second World War. Eight of the 10 listed authors are connected to the university.

Several master’s theses by ECU students contributed to various parts of the project, according to Joe Hoyt, lead author and national coordinator of the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries’ Maritime Heritage Program, ECU’s Coastal Studies Institute and Diving and Water Safety provided support for the field work through both diving and vessel operations. Hoyt earned his undergraduate degree in anthropology and his master’s degree in maritime history and nautical archaeology from ECU. Several of the other students involved have gone on to work for NOAA as well.

Interest in the project began with German U-boats, said Dr. Nathan Richards, director of Maritime Studies. Three of the German submarines were known to exist off the North Carolina coast, having been located and identified over the years since WWII, he said.

Around 2008, there was a report that someone was seeking to retrieve material from one of the U-boat wrecks, which was problematic due to issues of jurisdiction and the possibility of disturbing human remains.

“So in 2008 there was a collaboration to record a baseline,” he said. “When we refer to a baseline, we’re going to go out as archaeologists to record a site, and then we can measure changes of the site through time. … And that kind of opened the door to the consideration of this resource and of the untold story of the Battle of the Atlantic off North Carolina.”

In the waters off the state’s coast out to about halfway to Bermuda there are about 90 vessels known to have been lost in the war, Hoyt said. “For this study, we primarily focused on sites that we believed from the historic record would have been on the continental shelf … before it drops off into much, much deeper water.”

Documented in the report are 44 merchant vessels, seven Allied warships and support vessels, and four German military vessels. Some had been located and identified during the decades since the war. For a previously identified site, the researchers wanted to record a baseline of the current condition of the site.

“It’s capturing a snapshot in time of the level of preservation on those sites and getting an understanding of what’s there. And in some cases that required looking back at the identities that were ascribed to them and making sure that those were in fact accurate,” Hoyt said. “For sites that we knew historically had been lost but hadn’t been located again, those required a lot of search and survey.”

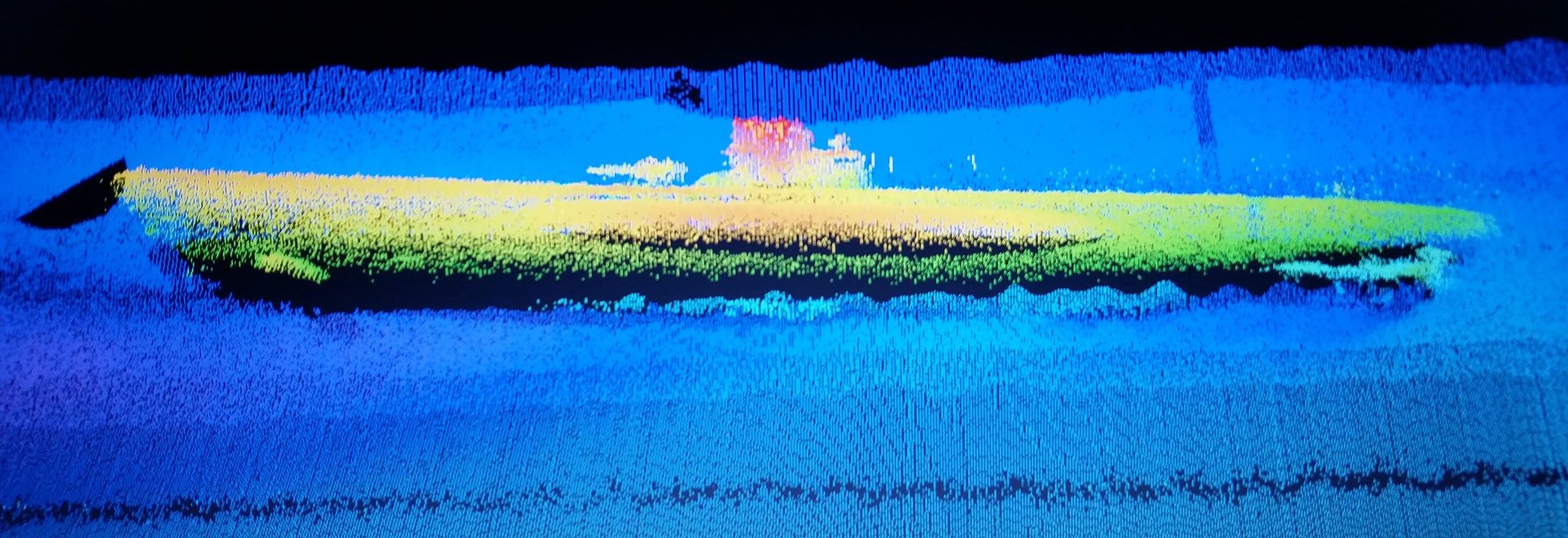

Researchers used a wide range of tools and techniques depending on what each site called for, including diving to record video and photography of the site, using manned and unmanned submersible vehicles, and sonar and laser scanning.

The E.M. Clark is one of 44 merchant vessels included in the Battle of the Atlantic report.

“In some cases we were testing out new applications of things,” Hoyt said. “Pretty much anything we could throw at it, we did.”

Richards said the work was incredibly diverse, but it was always exciting to actually investigate a site. “The work that we do involves incredible amounts of preparation and research before we do the diving,” he said. “We don’t just go diving … we’re always diving with the purpose of recording something efficiently.”

He credits Hoyt for his work in bringing together all the partners over the years and various sources of funding to support different kinds of research and answer different research questions, all of which contributed to the final Battle of the Atlantic report.

One of many notable discoveries was that of the freighter Bluefields, which was sunk by a German submarine.

“In July 1942 the U-576 attacked a convoy of 19 ships off Cape Hatteras and struck three of them,” Hoyt said. “One sunk immediately … but when it did this, the U-boat popped to the surface in the middle of the convoy in broad daylight, and it was attacked and sunk.”

The researchers obtained an American Battlefield Protection Program grant to search for the two vessels, and ECU student John Bright did his master’s thesis on the project. In 2014 the team located the remains of the two vessels, which lie just 240 yards apart in 700 feet of water, 35 miles offshore.

“So that was very, very exciting,” Hoyt said.

In August 2016, researchers visited the underwater battlefield using two manned submersibles, becoming the first people to lay eyes on the vessels since the day they sank 74 years before.

Hoyt said ECU’s maritime studies program and the diving safety team are second to none in what they do. “They just have an incredible training program for getting faculty and students trained up to the highest levels of scientific diving to be able to support this stuff,” he said. “I think it’s fair to say that this work would not have happened in the absence of ECU.”

John McCord, associate director of education and outreach at the Coastal Studies Institute, part of ECU’s Outer Banks Campus, also played a pivotal role as the main videographer and photographer, participating in most of the dives and producing photogrammetric models of sites and synopses of the expeditions.

Jennifer McKinnon, chair of the Department of History and associate professor of maritime studies, said such collaborations are vital to the mission of educating the next generation of maritime experts. “Students gain valuable experience by playing key roles in these collaborative research partnerships, including opportunities for conducting primary research through their own thesis projects and participation in field work and public outreach initiatives. Ultimately, the number of students that participated on this project and their subsequent success in the job market speaks to the importance of these partnerships.”

Now, thanks to the efforts of these researchers, agencies and institutions, there is a detailed record of the ships lost in action off the North Carolina coast during WWII.

Researchers documented each site using a variety of techniques, including manual measurements, photography and videography, and sonal and laser scanning.

Related

Operation Discovery

Forgotten Stories