College of Nursing Black history celebration focuses on acknowledging past, advancing future

Centuries of misconceptions about and mistreatment of African Americans continue to cause health care disparities among the Black community today. The ways these issues contribute to inequities and how health care providers can combat them was the focus of the East Carolina University College of Nursing’s sixth annual Black History Month event on Feb. 25.

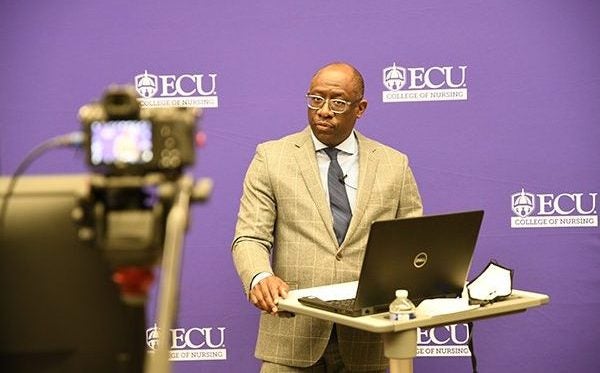

Dr. Mark Newell provided the keynote speech for the College of Nursing’s sixth annual Black History Month celebration, which was broadcast live to an audience of more than 150 attendees. (Photos by Conley Evans)

“Health Disparities in African Americans: Acknowledging the Past to Advance the Future” — planned by the college’s Black History Subcommittee led by faculty member Wendy Bridgers — was broadcast live from the College of Nursing and attended virtually by more than 150 students, faculty, staff and health care providers from ECU’s Division of Health Sciences.

Keynote speaker Dr. Mark Newell, Brody School of Medicine associate professor of trauma and surgical critical care, discussed how African Americans have been mistreated throughout history, including by health care providers, and how those events have caused ongoing health disparities among African Americans and eroded trust in health care professionals.

Newell cited examples such as Dr. J. Marion Sims, who became known as “the father of modern gynecology” for pioneering techniques and creating tools that were important for advancement of the profession but did so by conducting his research on enslaved Black women without using anesthesia in the mid-1800s.

He also discussed the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male,” which went on for 40 years before ending in 1972, enrolled 600 African American men — nearly 400 of whom had syphilis. Participants were told they were receiving free medical care from the government but did not receive treatment. Instead, they were given placebos and diagnostic procedures while the scientists and health providers that they had trusted to help them observed as the infection decimated their bodies. The experiment continued long after penicillin was discovered to be an effective treatment.

“Scientific racism — the belief that blacks had smaller brains and blood vessels, and a tendency toward laziness — allowed Blacks to be treated as inferior in an attempt to rationalize slavery,” said Newell, later discussing a 2016 study into racial bias in pain assessment that showed “a substantial number” of white laypeople, medical students and residents held false beliefs about biological difference between blacks and whites.

The successes of Black scientists and health care providers such as Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, who serves as the co-chief of scientists who developed the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine, were highlighted during the event.

“This allowed a system to be created that resulted in disparate living conditions, economic vitality, social opportunities and health and health care: the elements of what we refer to as the social determinants of health. These discrepancies and the social determinants of health contribute to the poor outcomes in Black people,” Newell said. “Vestiges of the belief that Black people are different remain solidly entrenched in today’s society.”

Newell also cited more recent examples of how disparities in education, housing, employment, income and other factors results in health care disparities among the Black community today.

“Where a person is going to receive their health care is often tied to their socioeconomic status,” Newell said, sharing data that shows increased infant mortality rates, pregnancy-related deaths, low birth weight, hypertension, diabetes, stroke and shorter life expectancy among Black individuals as compared with whites.

COVID-19 hospitalization rates among Blacks, he added, are five times that of non-Hispanic whites, while the death rate for Black people is 2.5 times that for white people.

Newell also highlighted the successes of Black scientists and health care providers such as Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, who serves as the co-chief of scientists who developed the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine, and Dr. Marcella Nunez-Smith, who heads the White House COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force.

“These doctors have succeeded because of the opportunity they were given, the opportunity to express their creativity, the opportunity to become what their creator planned for them to become, the opportunity to prosper, and in return, to serve; the opportunity to exercise their work ethic and their ingenuity,” Newell said. “Like all of black history, their accomplishments have not solely succeeded in profiting the black community, their successes have positively affected the lives of all Americans, if not the world.”

Newell closed his presentation by emphasizing the importance of recognizing the perceived differences between racial groups, how those perceptions lead to supremacist thoughts and actions, and how those thoughts and actions create a system of inequity.

“We have to eliminate the zero-sum game thinking that if I help you, I am taking away from myself, and understand that equity and opportunity profit us all,” he said.

ECU College of Nursing faculty member Wendy Bridgers and the Black History Month subcommittee planned the event that also included presentations on ethics in health care with two College of Nursing students.

Prior to Newell’s speech, College of Nursing students Micah Holmes and David Drogos, shared presentations of projects based on the Belmont ethical principles for research involving human subjects and examples throughout history of how black people were often not treated according to those standards.

Dr. Sylvia Brown, Dean of the College of Nursing, also shared the importance of having a student body and faculty that is reflective of the patients that they care for, and how the college is working toward those goals.

“It must be an expression of our actions as we make a significant difference in creating educational opportunities and improving healthcare access and erasing inequities that may exist in our college, within our profession and within society,” Brown said.

The College of Nursing’s Black History Subcommittee works to highlight the contributions of African Americans at East Carolina University, the College of Nursing and beyond. They aim to illuminate the historical significance of their struggles and celebrate their tenacity and diverse accomplishments.