BACK AT SEA

Acoustic wave glider deployed to investigate flounder migration

East Carolina University’s acoustic wave glider was deployed in December and January as part of an effort to determine the migratory pathways of southern flounder.

2015 ECU File Video | View this video on YouTube for closed captioning.

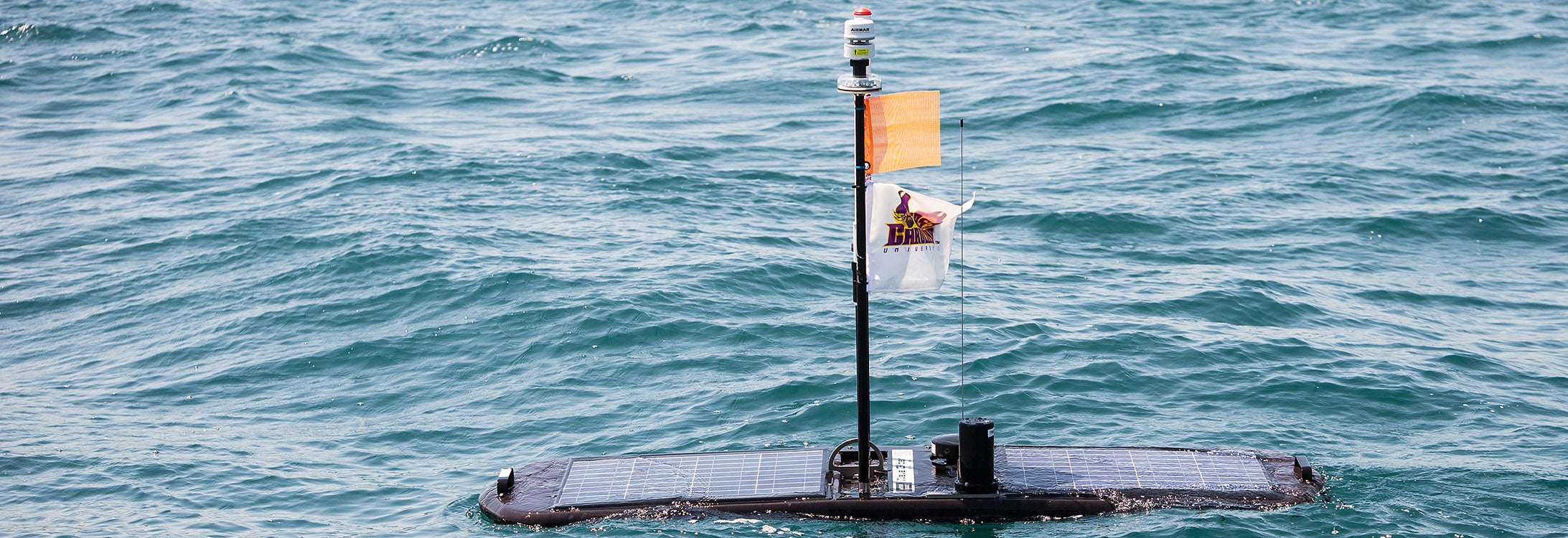

The device — nicknamed Blackbeard — is an ocean-going platform equipped with sensors to track environmental conditions, monitor and record sound, and identify tagged fish. A system of wings or fins below the platform converts wave energy into forward motion, and solar panels power the sensors.

First launched in 2015, Blackbeard has helped survey an artificial reef, and document fish and marine mammals off the North Carolina coast. Now, thanks to funding from the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries’ (NCDMF) Coastal Recreational Fishing License Program, the device is tracking southern flounder.

“Though the species is hugely popular, along with summer flounder, in the recreational fishery, and both are commercially important too, there is no knowledge of where southern flounder might spawn,” said Dr. Roger Rulifson, distinguished professor emeritus in the Department of Biology. “The stock in North Carolina continues to decline in spite of strong efforts by NCDMF to restrict harvests, and we do not understand why this is happening.

“The current fishery management plan for the species does not have any data on where southern flounder go once they leave our sounds and estuaries,” he said.

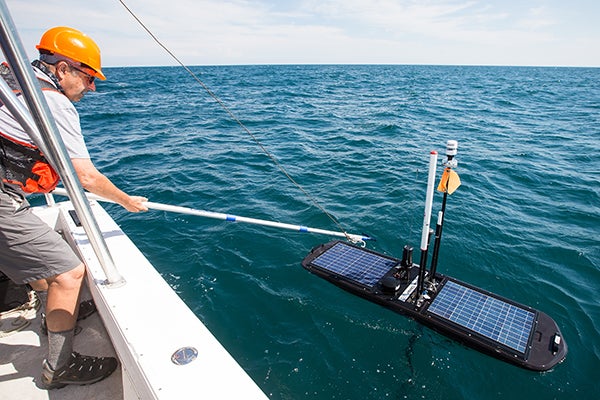

Researchers prepare to launch the acoustic wave glider from the ECU vessel R/V Cutting Edge in December. (Contributed photo)

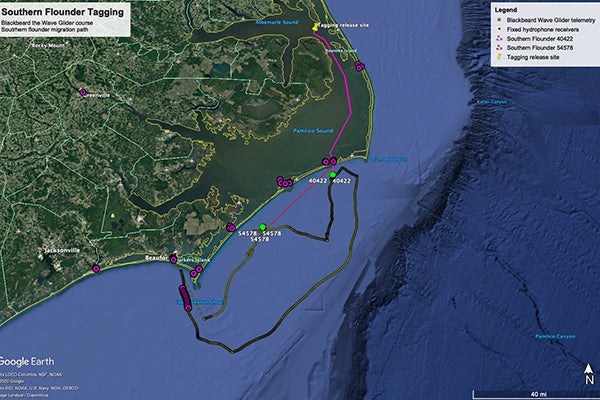

To try to locate flounder spawning grounds off the coast, the team worked with commercial fishermen to tag 110 fish with acoustic tags in October and November in the Albemarle and Pamlico sounds. Blackbeard’s mission is to search key areas offshore for the signals produced by the tags.

The project, led by Dr. Rebecca Asch, also includes Rulifson, Dr. Joseph Luczkovich and Dr. Patrick Harris of the Department of Biology; and Dr. Mark Sprague of the Department of Physics. Eric Diaddorio, ECU’s research vessel captain, is also a co-investigator and pilots the vessel used to deploy and retrieve the wave glider and has also deployed receivers anchored to the seabed in the state’s inlets and along the continental shelf.

Caitlin McGarigal is a biology technician and technical guru with the acoustic transmitters and receivers being used in the project, and there are two doctoral students — Tyler Peacock and Brian Bartlett — and a master’s student — Justin Mitchell — on the project as well, Rulifson said.

The wave glider survived an offshore storm in December, recording gale force winds up to 90 knots. It has also recorded signals from two of the tagged flounder, including one fish whose signal was recorded twice, more than 11 hours and 9 kilometers apart. The remotely operated craft’s progress is dependent upon wave action and affected by such obstacles as countercurrents and shipping lanes, and its array of sensors needs sunlight to charge the batteries.

Team members monitor the craft. (File photo by Cliff Hollis)

The device first launched in 2015. (File photo by Cliff Hollis)

Team members monitor not only the craft itself, but also the position and course of other ships and vessels, and can control the rudder to change course to avoid a collision or if sea conditions force a change in the mission plan.

“The good news is they’re leaving the inlets where they were tagged, and now they’re out in the ocean,” Luczkovich said. “We’re hoping to get the exact location out offshore where these flounders spawn, and then perform egg and larval fish collection out there.”

In December, the wave glider recorded signals from tagged flounder off the North Carolina coast. The fish were tagged in the Albemarle and Pamlico sounds. (Contributed image)

Asch said the southern flounder has historically been the most valuable finfish fishery in North Carolina, but the species is currently classified as being overfished.

“Managers have restricted the catch of this species to conserve its population, but this comes at a cost to fishermen,” she said. “As a result, it is imperative that we get the management right.”

One question is whether it makes sense biologically to manage the species at the state level or if management should be coordinated with other southeastern states, Asch said. The researchers hope to learn whether there are distinct populations of the fish in different areas or a single population shared by multiple states.

“By using Blackbeard to study the migration route of southern flounder, we hope to learn new information to address this question,” Asch said.

For more information or to follow Blackbeard’s mission, visit the Blackbeard Sails the Seas for Science Facebook page.

Related: Science on the Sea