THE ROAD TO DISCOVERY

Course-based undergraduate research leads to publication, grant

East Carolina University students in the Thomas Harriot College of Arts and Sciences often carry out impactful work in the classroom, but it is not every day that it leads to an international publication and nearly $300,000 in grant funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF). This is exactly what happened in the Department of Chemistry, where novel teaching methods, engaged faculty mentors and bright students provided the recipe for success.

Kristin Tyson received undergraduate degrees in chemistry and biochemistry and a minor in mathematics from ECU in 2019. During her senior year, she took advantage of class time in her Instrumental Analysis course to carry out Course-Based Undergraduate Research (CURE).

“Student research is an invaluable opportunity. It is a great way to learn what it will be like to do research in your major,” said Tyson, who is now pursuing a master’s degree in chemistry at ECU. “You are exposed to many different subject matters, and you are able to find and explore what interests you.”

In 2013, Dr. Eli Hvastkovs, associate professor of chemistry, redesigned the Instrumental Analysis course to incorporate more inquiry-based learning, and in 2018, he won a faculty development award from ECU’s Division of Research, Economic Development and Engagement for his CURE approach to teaching.

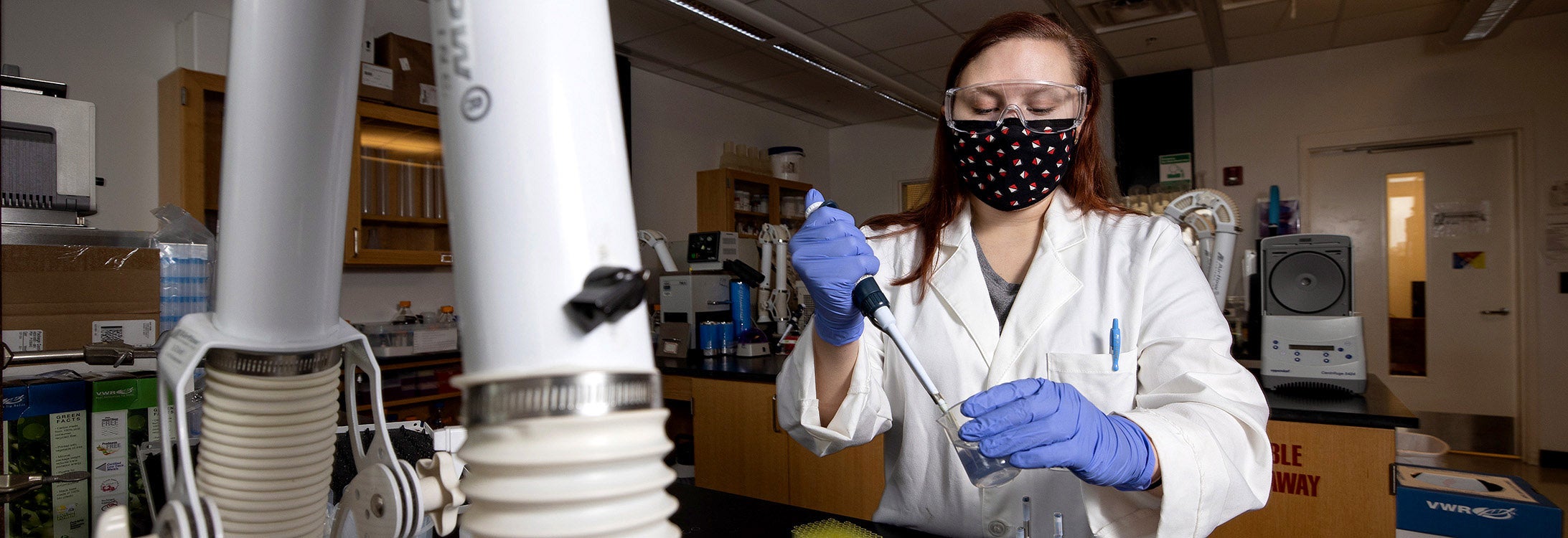

Tyson performs research in the chemistry lab at ECU.

By 2019, when Tyson enrolled in the course, Hvastkovs knew how to inspire students to ask questions to which the answers were not yet known. Tyson and her team, Amanda Davis and Jessica Norris (who is now pursuing a Ph.D. in chemistry at Penn State University), consulted with Dr. Adam Offenbacher, assistant professor of chemistry, and proposed to study a facet of how chemicals called proteins send messages in the body.

As is often the case when navigating a research project, the team did not reach a clear answer. But they tested a chemical reaction under a different solution condition (pH) and found an unexpected trend in the data.

In a specific protein called azurin, the students determined that a single tryptophan amino acid acted as a messenger, communicating between distinct regions of the protein.

“Fundamental discoveries like this help researchers understand how these proteins work so that they can design effective pharmaceuticals to treat a host of diseases,” Hvastkovs said.

The team’s discovery led to the writing and 2020 international publication of the paper, “Impact of Local Electrostatics on the Redox Properties of Tryptophan Radicals in Azurin: Implications for Redox-Active Tryptophans in Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer,” in the Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. Tyson’s paper was co-authored by students Davis and Norris, and ECU chemistry faculty Hvastkovs, Offenbacher and Dr. Libero Bartolotti.

“I was incredibly floored when my research was published,” Tyson said. “It took a while for the disbelief to fade, but when it did, I was very happy and proud.”

As a result of Tyson’s and subsequent students’ research, ECU is now the recipient of a three-year, $291,381 grant from the NSF for “Development of Unnatural Tryptophan Derivatives to Expand Tryptophan Function and to Study Biological Catalysis.” Co-principal investigators include chemistry faculty Hvastkovs, Dr. William Allen and Dr. Andrew Sargent. Undergraduate students who conducted the preliminary research included Tyson, Davis, Norris, Hanna Kosnik, David Murray, Amanda Ohler and Chris Whittington.

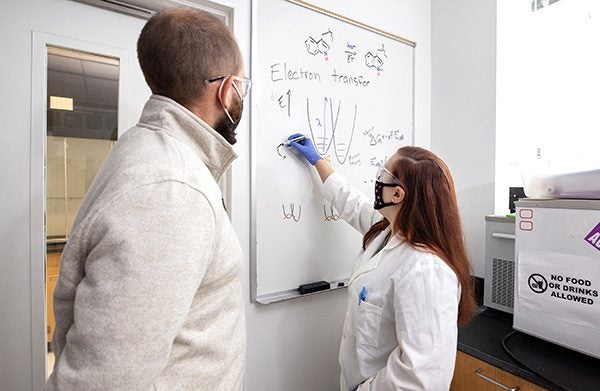

Tyson works out a problem in the lab with assistant professor of chemistry Adam Offenbacher.

“I’m proud that the CURE class has led to such an important finding, and that we were able to use this class as a catalysis to jump-start multiple young researchers’ careers as well as to secure a significant federally funded grant for the department,” Hvastkovs said.

“Indeed, Kristin’s paper helped to springboard the impact of the award,” said Offenbacher, who is principal investigator on the grant. Through the grant, the team will address the challenge of developing a new set of chemical tools that allow tracking of the messengers, or electrons, within and between proteins based on the amino acid tryptophan.

“While these unnatural amino acids have a similar appearance to their natural counterparts, they have unique functional properties that enable us to exploit them as chemical tools to track the movement of electrons, much like a molecular GPS. Our goal is to apply these tools towards a set of magnetic-sensing proteins in nature that are responsible for seasonal bird migration towards the development of new biosensors,” Offenbacher said.

The project uses a collaborative approach, combining molecular biology, chemical biology and theoretical chemistry, and facilitates multifaceted, hands-on research experiences.

Tyson said her research experiences have shown her that she wants to work in the pharmaceutical industry in the future.

“Working with Dr. Offenbacher has been a great experience, and I feel so much more confident as a chemist,” Tyson said. “I would not be as prepared to work in the field as a chemist without his guidance.”

Tyson shares her research problem with Offenbacher.