Study finds source of COVID-19 messaging impacts effectiveness

New research from a multi-institution team including an East Carolina University faculty member finds that messaging during the pandemic is more effective when attributed to a trusted health organization rather than the president.

The findings were published online on Aug. 27 in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

Researchers studied how the source of a COVID-19 prevention message affects its perceived effectiveness. The team included ECU associate professor Joseph Lee, UConn Health’s professor Howard Tennen, Marcella Boynton, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Ross O’Hara, a former UConn Health postdoctoral fellow and independent researcher from Michigan.

Joseph Lee (File photo)

Lee is interim director of the ECU School of Social Work in the College of Health and Human Performance, affiliated faculty member in the Center for Health Disparities at the Brody School of Medicine, and associate member of the Cancer Prevention and Control Program in the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

From May 31 to June 16, the researchers engaged a diverse group of nearly 1,000 American adults to test the effectiveness of different messages encouraging coronavirus safety measures such as wearing a mask or social distancing. Messages systematically varied, including who was attributed as the source of the message. Participants were told messages came from President Donald Trump, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Trump and the CDC, a local or state health agency, or no source.

The team found when Trump’s name was associated with the message, the effectiveness of those messages decreased, not just compared to other sources, but even when there was no source.

Boynton, who previously studied how to effectively communicate the health risks of tobacco use, thought the current public health crisis called for the same kind of research methods to identify the best way to get credible, evidence-based prevention messages to the public.

The researchers found even participants who said they trust Trump did not find messages from him more effective compared to other message sources. However, those who said they do not trust the president found the messages significantly less effective when associated with Trump.

“Linking President Trump to prevention messages seems to work to the detriment of what those messages were trying to do,” Boynton says.

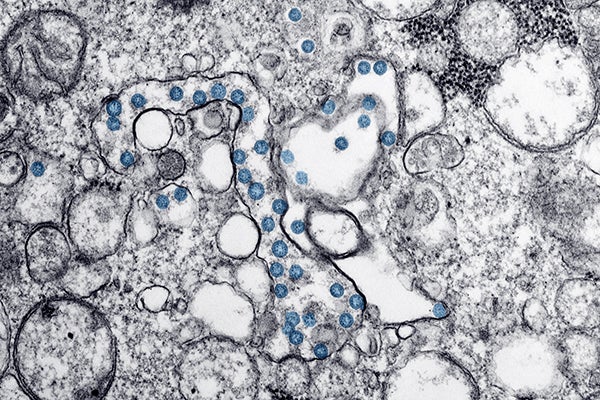

Transmission electron microscopic image of an isolate from the first U.S. case of COVID-19. The spherical viral particles, colorized blue, contain cross-sections through the viral genome, seen as black dots. (Photo courtesy of the CDC)

The findings are important as various agencies and news outlets try to determine the best strategies to ensure prevention messages are as effective as possible.

While this study asked participants to evaluate only their immediate reactions to the messages, other studies have shown that these reactions tend to be good indicators of future behavior.

“Given the toll of the pandemic, it’s so important to make sure messages are as effective as possible in promoting healthy behaviors,” Lee said. “I’m proud ECU is a part of this project identifying strategies to improve the effectiveness of coronavirus prevention messages.”

The team hopes to complete a follow-up study examining how these types of messages affect people’s engagement in prevention behaviors such as wearing a mask.

The study was funded by the Institute for Collaboration on Health, Intervention and Policy, a multidisciplinary research institute based at the University of Connecticut.

The University of Connecticut communications team contributed information for this story.