DIGITAL FIELD EXPERIENCE

Students study geology in New Mexico, Colorado in first virtual summer field course

An important part of instruction received by a geological sciences major at East Carolina University includes knowledge and skills gained in the field. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, student experiences went digital this summer.

“Field experiences are of great importance in teaching geologic concepts to undergraduate students,” said Dr. Steve Culver, chair of the Department of Geological Sciences. “It requires imagination and a lot of hard work to transfer instruction from the real world to a virtual world. Dr. Farris and colleagues did an important job by continuing to provide the conceptual knowledge and the practical skills that will enable students to succeed in their careers.”

Dr. David Farris, assistant professor of geological sciences, directed the newly revised virtual field course that ran May 18 through June 22. Farris, who came to ECU last fall 2019, has directed similar field courses in New Mexico and Colorado at other institutions since 2013, though this was his first time leading a virtual course.

At the Rio Grande Gorge, near Taos, New Mexico, the Rio Grande incises sharply through the Taos plateau exposing young 3 to 4 million-year-old lava flows of the Servilleta Formation. The Sangre de Cristo Mountains can be seen in the background. (Contributed video)

“The tools we have now allow for a much more immersive online experience than in the past,” Farris said. “However, it can only go so far in terms of replacing the field environment.”

In the past, students would spend approximately six weeks in Colorado and New Mexico, where they would venture into the field, examine and collect data, and then create geologic maps.

Copper Hill a.k.a. Rattlesnake Gulch, near Dixon, New Mexico, is one of the field course mapping areas. Here, garnets are faceted within this exposed rock.

“It was definitely a change from how this course has been taken in the past,” said senior geology major Sidney Green, who will earn her degree in December with concentrations in environmental geology, and coastal and marine geology. “Although we missed the experience of collecting field data, we were still able to see photographs and virtual reality photospheres of these sites.”

One of the key skill sets students acquire in the field is how to take geologic observations and build them into coherent products. One example of this is taking rock type and structural observations at individual outcrops, turning them into geologic maps, and then using the maps and cross-sections for reports and papers.

The new, online version of the field course was a combination of projects and virtual field trips to introduce students to the broader geology of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado and focused more on the mapping and writing aspects.

“The format of the virtual field course was interesting,” said senior geology major and field course participant Patrick Tomasic.

Tomasic, who plans to attend graduate school, said he enjoyed learning how to use different software platforms and techniques to complete the projects, which will help him in the future.

Earlier in the spring, Dr. Stephen Moysey, director of the ECU Water Resources Center and professor of geological sciences, led a working group to redesign field courses into a remote experience. The project was a joint effort between the National Association of Geoscience Teachers and the International Association for Geoscience Diversity.

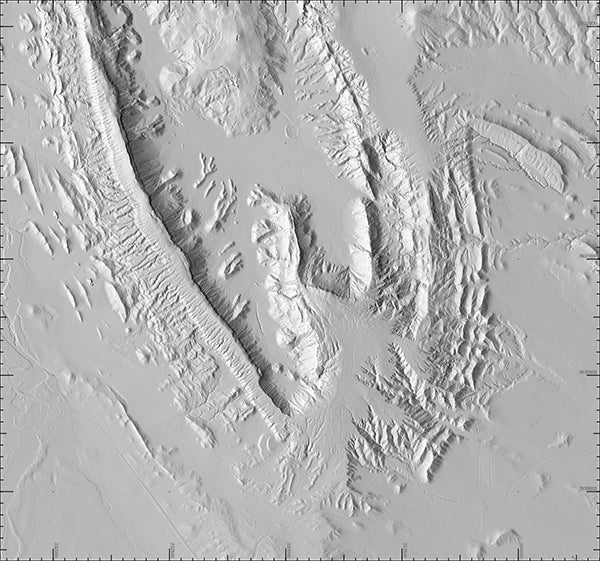

A high-resolution digital elevation model of San Ysidro, New Mexico, was used in the one of the mapping projects in the online course.

View one of the 360-degree photospheres on Google Earth

Within eight weeks, Moysey’s team developed online activities and resources to support the immediate transition to distance learning of field experiences for more than 250 colleagues around the world.

Farris worked with Moysey on a variety of virtual components that students used during the summer course, including a number of photospheres. A photosphere is an image taken with a 360-degree camera that allows the viewer to look in any direction, as if they were standing at that location. The images can be viewed with a headset or on a computer.

“Getting the field data provided to you is not the same as collecting it in person, but students received a similar experience integrating geologic data and coming up with an interpretation,” Farris said.

Through their coursework, students received a geologic tour of an area — for example, White Mesa or San Ysidro — based on field photos, videos, virtual reality photospheres, remote sensing data, and an introduction to the various geologic units. Then, according to Farris, students had to build a map, draft a cross section and write a geologic report or paper.

Green appreciated the freedom the course allowed, meeting daily for discussions and project objectives, but also being able to access class videos in Canvas at later times.

“Since a lot of us currently have jobs, the freedom to work on your own time was really nice,” Green said.

Although she was worried at first that she wouldn’t learn as much from an online course, Green said she was wrong; she enjoyed the class a lot and learned several news skills.

Sidney Green looks through a polarizing petrographic microscope at a thin section of rock to examine its characteristics and determine its mineralogy.

Patrick Tomasic, a geology major who took this summer’s virtual field course, said learning the software platforms and techniques will help him in the future.

“We used many programs like GIS, Adobe Illustrator, Google Earth and virtual reality sites that will be useful for future jobs,” Green said. “I was worried about not having as much field experience as others who have taken this course in the past, but getting familiar with these programs is something they haven’t been able to do with this course. We got to see a different side of the work we will have to do in future jobs.”

“Up until recently, all projects were done by hand,” said Tomasic. “I would prefer to look at outcrops in person. However, with the circumstances that forced the course to move online, the idea of virtual tours was really a cool idea.”

The Great Sand Dunes National Monument in Colorado contains the tallest sand dunes in North America, reaching up to 750 feet high. The Sangre de Cristo Mountains can be seen in the background.