RESEARCHING MUSCLE FUNCTION

ECU researchers find potential way to improve activity of heart, skeletal muscles

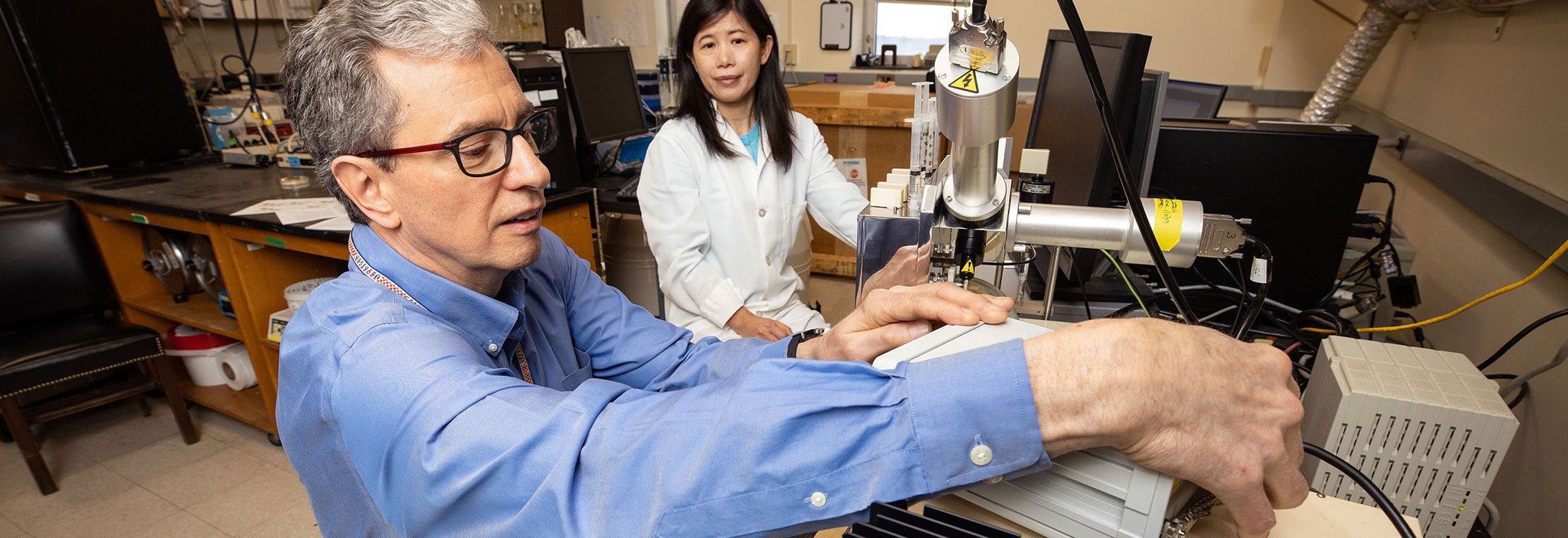

East Carolina University researchers – in collaboration with researchers from Florida State University and the University of Hannover, Germany – discovered that a small region in the cardiac protein, troponin T, is critical for the regulation of cardiac muscle contraction.

Dr. Joseph Michael Chalovich, professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at ECU’s Brody School of Medicine, said this work raises the potential for developing new targets for drug development to manage heart disease and possibly skeletal muscle disorders.

“Proteins, like troponin T, are made up of 20 molecules called amino acids; it’s like building something with Legos… If you put the wrong ones in you’re going to get something that’s a different shape and has a different function. So we found out which little Lego blocks, if you will, are important,” Chalovich said. “And once you have that information, you’re able to start designing something that can counteract those effects.”

The researchers recently published a paper in The Journal of Biological Chemistry that showed certain positively charged amino acids in troponin inhibit normal activation of muscle by calcium. Chalovich said scientists might eventually be able to increase the force produced by muscle by altering these charges, which could be important in treating disorders of heart and skeletal muscle.

“You have to understand how something works before you can fix it,” he added. “And right now we’re in a transition period where we’ve found something new. That adds to our understanding of how it works, and now we’re starting to think we change that to make it work differently.”

Chalovich has been at ECU for more than 35 years, researching how both cardiac and skeletal muscles contract.

“We’re interested in how the muscle is turned on and off. Because if the heart muscle stops working, you’re dead. And if you’re skeletal muscles stop working, you can still be alive but your life is much less pleasant,” he said. “We’re studying these components of both muscles that tell the heart or skeletal muscle to move or to relax.”

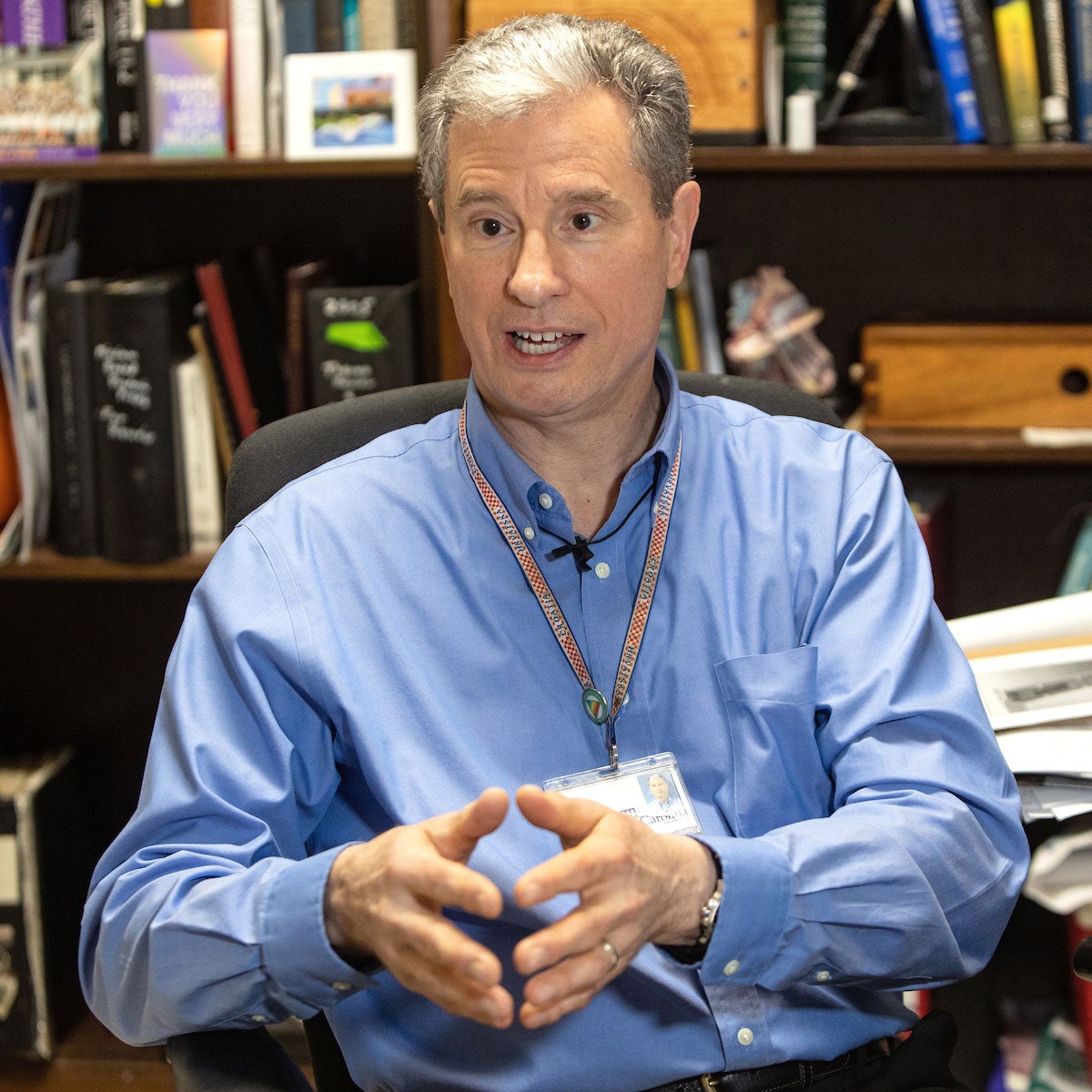

Dr. Joseph Michael Chalovich, professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at ECU’s Brody School of Medicine, discusses his research into heart and skeletal muscle function.

About 20 years ago, however, a pair of European cardiologists approached Chalovich after he gave a seminar on his work in Germany and said that they thought his approaches could shed light on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a disease where the heart muscle becomes abnormally thick, making it more difficult for the heart to pump blood.

“In the heart and in the skeletal muscle, the things that make the muscle work are two proteins – actin and myosin – and there are many components involved in telling those two proteins to either produce force and shorten, or to relax,” Chalovich said. “When you’re born with a defect in one of these regulatory components, the heart doesn’t work quite right.”

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy often goes undiagnosed because many people with the disease can live long lives and rarely show any symptoms. But it is a common cause of sudden cardiac arrest in young people, particularly young athletes.

“They can have an assault when they are under severe stress during athletic activities. Those athletes are the ones that you hear about dying because they’re pushing their body to the limit and the heart just can’t transport enough oxygen from the lungs to the body,” Chalovich said. “So we started off by being interested in how normal muscle works and then we got interested in this disease.”

The ECU researchers then began studying several mutants of cardiac proteins and one mutation of troponin T stood out, which was a deletion of the last 14 amino acids of troponin T containing the positively charged amino acids.

“What we found is that if you take a that little piece of troponin T off, as occurs in some disorders like hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or remove the positive charges, then the regulation works totally differently – you don’t fully relax. But when you add calcium you can get enhanced activity,” Chalovich said. “And so with the heart muscle, if you take off this little piece of one of the components of troponin T, then add a submaximal level of an activator calcium, you can get a maximum contraction … which could be useful for treating heart failure and some skeletal muscle disorders.”

While Chaolovich said the researchers’ most recent discoveries were exciting milestone following more than two decades of work, he said the real-world benefits of this research could take many years to reach patients – if they ever do.

“Most people spend their whole careers working on something and not seeing it go to fruition such as treatment of a disorder. But they also know what they found laid the foundation for other research,” he said. “Even if you don’t produce something that ends up in a pill that’s going to help somebody, you know that you’ve helped everybody along the way. And that’s what we’re doing here.”