MYSTERIES OF THE DEEP

ECU’s Program for Maritime Studies dives into history

Maybe more than most, students and faculty in the East Carolina University Program for Maritime Studies live a Pirate’s life, diving deep into the robust maritime history of coastal North Carolina and uncovering mysteries throughout the world.

They’ve traveled everywhere from the muddy waters of Pamlico Sound to the clear blue of the South Pacific, researching everything from artifacts of the infamous pirate Blackbeard’s ship Queen Anne’s Revenge to World War II aircraft wreckage 30 feet below the surface of the sea.

“This makes me happy,” graduate student Aleck Tan said of the program. “Sometimes I think about doing something that would make me more money. Underwater archaeology isn’t something you go into thinking you’re going to make a lot of money. You just think about protecting and preserving cultural resources for the future. I realized during my undergrad I wanted to do that, so this is a dream.”

ECU’s program started in 1981 when Dr. William Still and Dr. Gordon Watts translated their passion for Civil War history into an effort to study shipwrecks of that era in eastern North Carolina.

Meaningful Discoveries

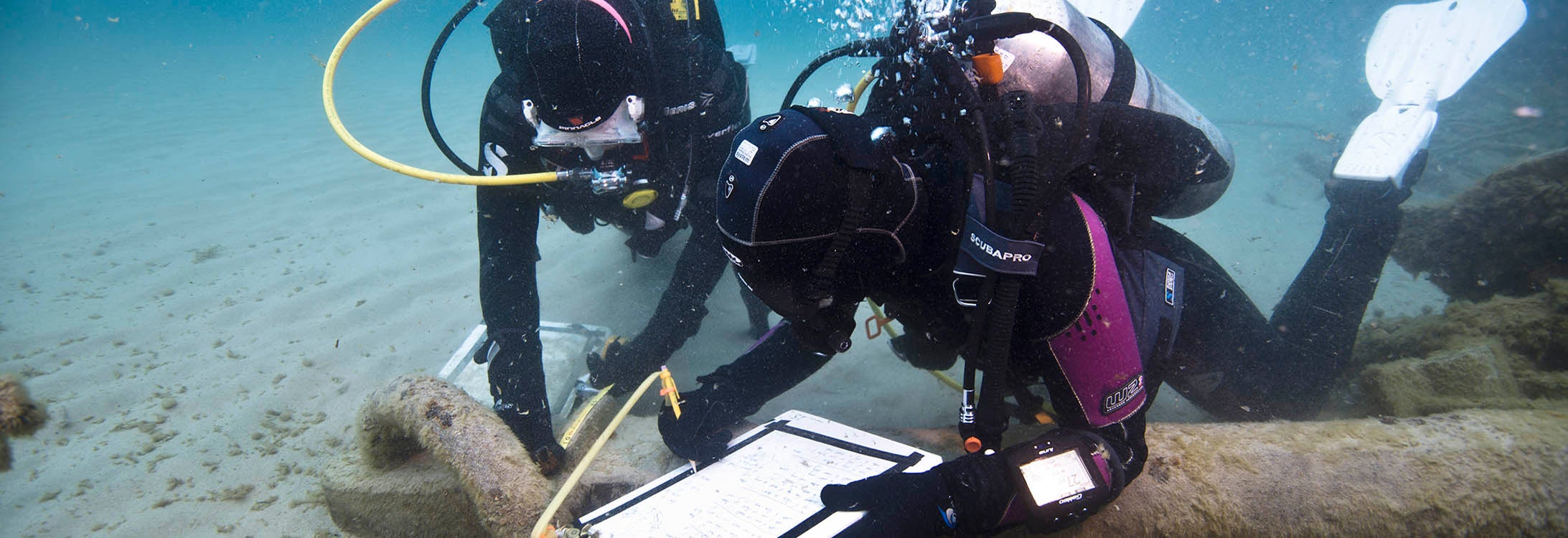

About 70 students are currently enrolled in the program, which includes field schools where students travel and dive on various sites. Recently, students and faculty traveled to Italy and Saipan where aircraft from World War II rest at the bottom of the sea.

“There are missing service members who went down with the aircraft, whether pilot or crew or a combination of those,” said Dr. Jennifer McKinnon, associate professor who has led those trips. “Our jobs as underwater archeologists have been to characterize the sites — is the site there, what does it look like, what is the potential for an eventual recovery of lost service members.”

ECU is working with the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) on those sites as well as with the Task Force Dagger Foundation, a nonprofit group that helps wounded or ill U.S. Special Operations Command members and their families.

McKinnon said the work can be therapeutic for Task Force Dagger members, some of whom have amputations and others who may have traumatic brain injuries or post-traumatic stress.

Students Molly Trivelpiece and Ryan Miranda prepare to enter the water during a field school in Saipan. (Photo by Jennifer McKinnon)

“This provides them a specific ‘mission, purpose and focus’ for them whenever they can participate in these types of projects,” McKinnon said, referring to the foundation’s motto. “It’s very touching whenever you talk to them. You see it on their faces. They know the meaning of how important it is to try to recover the pilot out of this lost aircraft.”

Tan accompanied members of Task Force Dagger on the trip to Saipan where she participated in her first excavation as a student in the program.

“We were excavating that site, and it was pretty humbling and just an overall great experience,” Tan said. “It goes full circle. You’re trying to find remains from World War II while you’re working with people who are veterans who were very motivated to find those remains and fulfill their mission.”

McKinnon said the dives are important for their educational value but more important for the people they affect.

“We need to discover and learn stuff, but I think these kinds of missions are very practical and applicable and have real-world consequences to them, which are that family members will find closure if these projects are successful,” McKinnon said. “I think that’s where you see where research intersects with community and people.”

Unique Program

ECU’s maritime studies program is one of just three in the nation. It draws students and faculty from throughout the world.

“We are unique in the state. We are unique in the region. We’re rare in the nation, and we’re here in Greenville, and we have one of the best — and I would say the best — program in the nation if not the world,” said Dr. Nathan Richards, associate professor and director of the program, which is part of the Department of History. “We’re international and we attract international people, but we’re also working in the community and we’re interested in looking at the history in our region.”

Richards grew up in Australia, combining his love of history and his passion for scuba diving into maritime archaeology.

“I get seduced by these maritime archaeological sites,” Richards said. “They often hold mysteries like the identity of a ship and what is its history and what type of ship is it. I go down the rabbit hole of here’s a site that most people think is a pile of junk that turns out to be some amphibious assault landing craft from the Second World War. The research is what transforms that ‘junk’ into something that holds meaning and something that people will then feel a connection to, something that someone’s grandfather once served on and has this depth of history and has all of these hidden layers. Through your process of research, you’re discovering it for yourself, but you’re also discovering it for other people.”

He said maritime archaeology is a key part of learning about past cultures and people.

“It often reinforces the historical information that we have, but often may refute or redefine it,” Richards said. “It might tell us a different story. Archaeological research often tell us stories that we don’t have historical records of.”

Ryan Miranda deploys a side scan sonar during a search for missing Allied aircraft during the 2018 field school in Saipan. (Photo by Jennifer McKinnon)

He said ECU’s program is notable in that it offers many collaborative efforts among the faculty as well as with other colleges within the university. The field projects offer variety, such as mapping artifacts in Costa Rica, diving on a World War II shipwreck off North Carolina or documenting shipwrecks in Lake Huron.

“It’s years of research and years of planning, and then it comes together in the field,” Richards said. “The great thing about maritime archaeology is, after all that time in the library or at the desk and on the internet or in a book, seeing it all come out and unfold in the field in a very intensive period of time when you’re on the bottom of the ocean somewhere, seeing if all of your earlier assumptions are correct or if there are other surprises that the archaeological record holds for you. No two projects are ever the same. They’re all different, so that’s interesting and exciting.”

Tan said the work in the field is the highlight of the program.

“This program really gives you opportunities to be in the field and to learn as much as you can,” she said. “I think that’s what I love most about the program. … The projects are amazing. You’re out in the water and are with the people you’re working with and learning from.”

Each dive and each artifact reveals a piece of history, which in the end, identifies who we are today, Richards said.

“People have an inherent interest in history, especially when we’re talking about the history of the United States, the history of any particular group of people, the role of historical narrative in shoring up and consolidating people’s sense of self and identity,” Richards said. “… I can be working in 3 feet of mud in Pamlico Sound and be just as happy as working in 20 feet of crystal blue water in Saipan because all these sites, if you are looking at them in a particular way, they all have stories to tell. They are connected to people; they are connected to landscapes. They are connected to major events and processes of human history. That’s all very exciting.”

For more information in ECU’s Program in Maritime Studies, visit http://www.ecu.edu/cs-cas/maritime/.