ECU researcher testifies in front of Congress on the dangers of PFAS

A researcher at ECU’s Brody School of Medicine testified before a U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee Wednesday, May 15 about the negative health effects of chemical compounds that are estimated to be in the drinking water systems of 19 million Americans.

Dr. Jamie DeWitt, an associate professor in Brody’s Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, has been featured by National Public Radio, Bloomberg, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and StarNews Online.

Full story below

GenX – PKG – Clean

GenX – PKG – CC

Download instructions: To download a video, click play then right-click and select “Download” or “Download As.”

ECU researcher to testify in front of Congress on the dangers of PFAS

Chemical compounds estimated to be in drinking water systems of 19M Americans

By Rob Spahr

University Communications

A researcher at ECU’s Brody School of Medicine testified before a U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee Wednesday about the negative health effects of chemical compounds that are estimated to be in the drinking water systems of 19 million Americans.

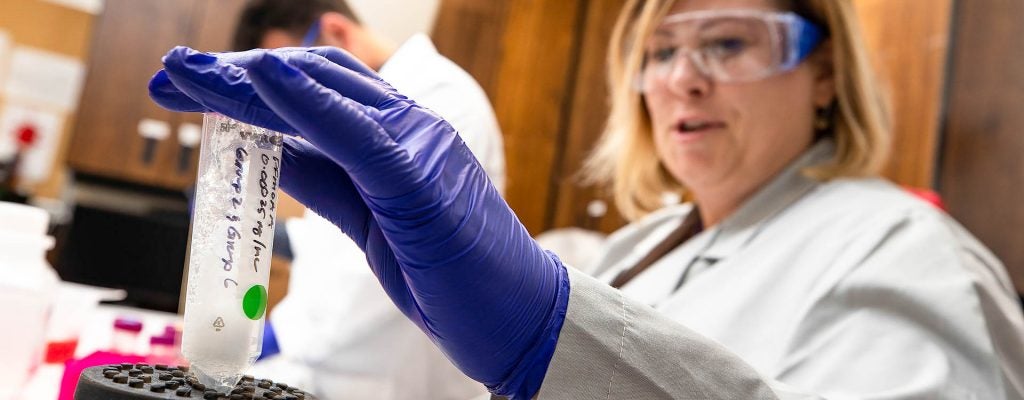

Dr. Jamie DeWitt, an associate professor in Brody’s Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, discussed the human health risks of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in front of the U.S. House of Representative’s Committee on Energy and Commerce’s Subcommittee on Environment and Climate Change.

“Our scientific understanding of the health effects of PFAS is still growing. Of the 5,000 PFAS, two have been very well studied and a handful have limited data,” DeWitt told the subcommittee.

DeWitt explained that a comprehensive evaluation of toxicological data for 14 different PFAS compiled by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry found that populations of people exposed to PFAS experience a variety of health effects, including:

DeWitt’s testimony begins at the 42-minute mark.

- Decreased antibody responses to vaccines

- Liver damage

- Changes in serum lipids and cholesterol

- Increased risk of thyroid disease, asthma, decreased fertility, pregnancy-induced preeclampsia and hypertension

- Decreases in birth weight

- Increased incidences of kidney and testicular cancer.

“These health effects indicate that developing organizations, the immune system, the endocrine system and metabolic systems all are sensitive endpoints to PFAS exposure. These also indicate that PFAS have carcinogenic abilities,” DeWitt explained

The two-hour hearing – entitled “Protecting Americans at Risk of PFAS Contamination and Exposure” – included bipartisan discussions on a series of PFAS-related bills currently being considered by lawmakers.

DeWitt urged Congress to regulate PFAS as a class of substances instead of individually.

“Of the 5,000 known PFAS, the vast majority have no associated research data or standards for human biomonitoring. But it’s not really feasible from a time or resource perspective to ‘test’ our way out of this crisis,” she said during her testimony. “Employing a ‘class’ approach for all PFAS will be protective for vulnerable subpopulations as well as the general public – it’s not too late.”

PFAS are human-made chemicals – such as PFOA, PFOS and GenX – that have been manufactured and used in a variety of industries since the 1940s. These chemical compounds are commonly found in commercial household products, industrial facilities, drinking water and food grown in PFAS-contaminated soil or processed with equipment that used PFAS.

DeWitt, who was recently featured by National Public Radio,The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and StarNews Online, has been studying the immunotoxicity of PFAS since 2005 and is part of a collaborative with investigators at North Carolina State University, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, UNC-Wilmington, UNC-Charlotte, North Carolina A&T and Duke University that received $5 million in state funding to study the health effects of the substances.

The North Carolina Legislature allocated the $5 million to the N.C. Policy Collaboratory, which disseminated the funds to experts at these universities to conduct PFAS-related research. State officials have said this research model is the first of its kind in the United States.

“I think we are very fortunate to be in a state that has a university system that really makes it possible to bring together our collective expertise for the benefit of the residents of this state,” DeWitt said previously. “This is a use of taxpayer money that is going to address a problem of direct relevance, right now, to citizens who are drinking water that is contaminated.”

During the next year, DeWitt’s team plans to study at least six different PFAS compounds and conduct at least one mixture study to find out how the immune system responds when it is exposed to the chemical compounds.

“The question is: ‘If your body is exposed to a PFAS, can your body make an appropriate immune response?’” DeWitt said. “We ask a few more detailed questions to help us to understand what cells might be involved … but basically, we’re asking the immune system to respond to a vaccine challenge after it’s been exposed to a PFAS.”

According to the N.C. PFAS Testing (PFAST) Network, PFAS are found in a wide range of consumer products that are used daily, such as cookware, pizza boxes and stain repellents. Therefore, a majority of the population has been exposed to PFAS, some of which can accumulate and remain in the human body for a long time.

In addition to her work with the N.C. PFAST Network, DeWitt was one of three national experts recently named to the Michigan PFAS Action Response Team’s Science Advisory Workgroup, which will help Michigan officials set an enforceable drinking water standard for PFAS. She is also part of an EPA-funded research effort – led by a team from Oregon State University – that is investigating the effects PFAS compounds have on humans.

“Receiving this funding from the EPA further demonstrates that we have the expertise here in the state to address a problem of not only local and national concern, but of international concern,” DeWitt said. “This is not a North Carolina-specific problem. These compounds are also a problem in other countries, and I am working with a group of international scientists to come up with a solution to the PFAS problem.”

Contact: Rob Spahr, University Communications, 252-744-2482, spahrr18@ecu.edu