MEDICAL STUDENT BUS TOUR

ECU professor gives medical students valuable, candid tour of Greenville

Groups of first-year medical school students boarded an ECU bus on Aug. 1, knowing only that they were going to get a tour of Greenville.

What they actually received was a priceless oral history of the city dating back to the 1940s – through times of segregation and controversial urban renewal – from a tour guide who lived through it all and who wants the next generation of doctors to be better equipped to serve the community.

“It is my firm belief that this institution – an institution in ECU whose motto is ‘Servire,’ the Latin word for ‘to serve’ – is placed in an area and that we ought to be serving right here. Not just by training and educating, but also by serving the community,” said Dr. Tom Irons, professor of pediatrics and associate vice chair for health services at ECU’s Brody School of Medicine.

First-year medical students take a historical tour of Greenville. (Photo by Cliff Hollis)

Irons said he has been giving this tour to medical students and pediatric residents for many years because he wants them to know that within a half mile of Brody there are “neighborhoods where health status indicators are terrible. Neighborhoods where the HIV rate approaches 25 percent, and where preventable cancer rates are 400 percent above other areas of North Carolina.”

“It’s important for them to know the community, because these are our patients,” he said. “It’s important for them to know, because what determines our health is not access to health care. It’s education, it’s economics, it’s social support. … I want them to know what makes our patients sick and what we can do about that, and the only way to do that is to get to know the people.”

The first place that Irons took the students was to the Pitt County Office Building.

The building originally operated as Pitt County Memorial Hospital and was constructed under the Hill-Burton Act of 1946, which required new hospitals funded through the act to serve all patients, regardless of their race.

Irons said the Hill-Burton Act helped to address some major problems, including giving African-Americans access to health care and providing a “reasonable” amount of free care to residents who could not afford to pay.

“Soldiers were coming home from World War II – African-American men who had distinguished themselves in service – to counties all over this country where they could not get health care,” Irons told the students. “It was shameful.”

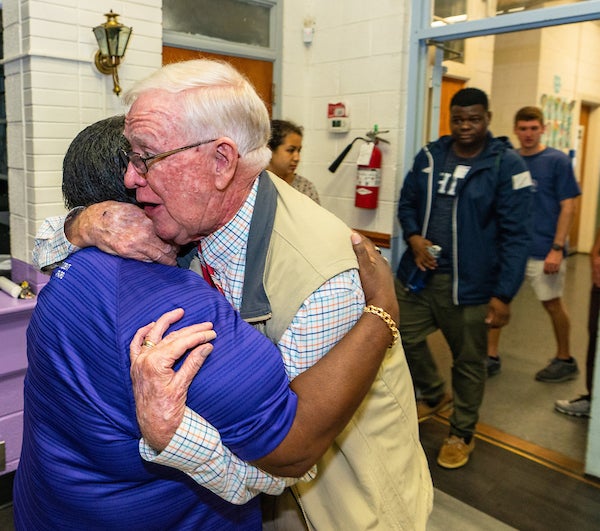

Deborah Moody, director of the Lucille W. Gorham Intergenerational Community Center, greets Dr. Tom Irons. (Photo by Cliff Hollis)

While Irons said the Hill-Burton Act improved that situation, he said it also had a “dark side.”

“In order to get the votes needed to pass the Hill-Burton Act and to build these hospitals, they had to codify in law that the hospital would be fully segregated in every way,” he said. “And ‘separate but equal’ was part of the law, but it certainly was not equal. The ‘colored ward’ was understaffed and underequipped.”

As a result of these issues, it was in that hospital’s “colored ward” where Irons’ mother, a pediatrician who promoted desegregation, required him to start helping her with patients as soon as he was old enough.

“I got my baptism holding a baby for a spinal tap when I was 12 years old,” he said. “She made me her assistant, which really changed me and made me into a doctor.”

After the former hospital, Irons took the students through Greenville neighborhoods, to the sites of former schools and churches that were important to the African-American community, to the James Bernstein Community Health Center and into the Lucille Gorham Intergenerational Center.

The tour’s final stop was a visit to the Community Crossroads Center on Manhattan Avenue.

“It’s where they can not only see a homeless shelter, but a place where we work to transition people back to independence and therefore improve their health status and their wellbeing,” he said.

Each stop was accompanied with a personal story, historical context and explanations of modern relevance.

“Doing the right thing is the important thing, and that’s a big deal for me,” he told the students.

For Irons, one of the highlights of this year’s tour was to see current Brody medical students – and past tour participants – volunteering at one of the stops, something they spent their entire summer doing.

“I was bursting with pride,” he said.

Dr. Tom Irons tells medical students about the historical significance of Greenville’s Town Common. (Photo by Rob Spahr)

First-year medical student Lynnee Vaught said she grew up three hours from Greenville, in Clemmons, so she admittedly did not know much about the city prior to the tour.

But she said hearing stories from Dr. Irons about the struggles Greenville has faced – from segregation through the flooding from Hurricane Floyd in 1999 – already had her and several of her classmates discussing plans to volunteer on weekends to help the community.

“We’re going to learn how to treat people with the science and medical knowledge that we have, but I also think that it also drives home that we’re in the science and the profession to help those in need,” Vaught said of the tour.

First-year medical student Tijesuni “Tj.” Babalola said the tour – and the passion of Dr. Irons – helped him better understand the importance of “service” and gave him more of an appreciation for the medical school he attends.

“I thought it was great because he didn’t sugarcoat it, he let you know how it was,” said Babalola, who has lived in Harrisburg since moving from Nigeria at age 9.

“And I definitely took away that as future providers in eastern North Carolina, or anywhere that we end up, you have to show the patients in the community that you care,” Babalola added. “And you do that by going out and interacting with them, being part of the community and talking to them about their daily lives.”

Irons said he shares so many stories from his own life and the lives of his doctor parents, who moved to Greenville in 1946, because he wants the students to see how closely everything is tied together.

“We’re all woven together. In fact, that’s why we have a responsibility to serve these neighbors across the street. Because they are our neighbors, they are our brothers and sisters,” he said. “The only way I can do it is to lay it on the context of my own life, mistakes I’ve made along the way in learning how to do this right and help them see ways that they can do something themselves when they enter the community later.”