FISHY FINDINGS

Assistant professor uses zebrafish to study brain development

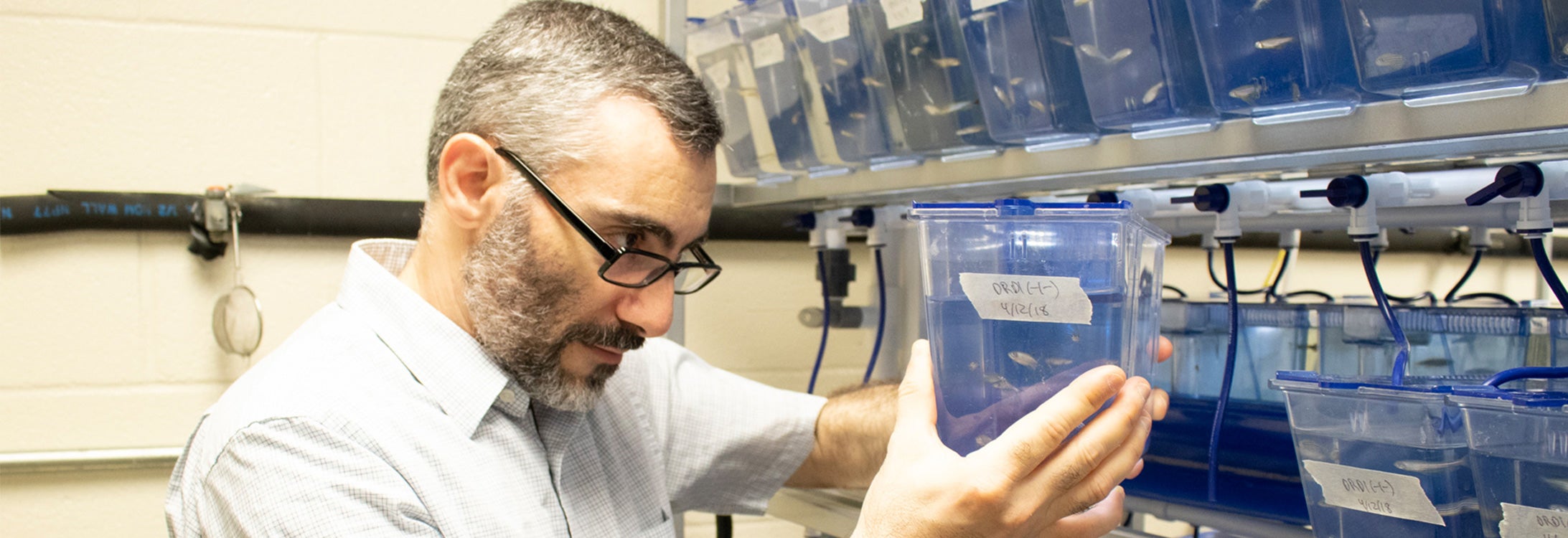

An East Carolina University researcher is studying the effects of social behavior on nervous system function and development in a most unlikely place – a fish tank.

Spearheaded by a four-year, $470,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, Fadi Issa, an assistant professor of neurobiology, is exploring the connection between social hierarchy and its effect on behavior and neurological development in zebrafish.

Issa, who joined ECU in 2014 after a six-year postdoctoral stint at UCLA, said that by observing zebrafish, researchers can learn a lot about how our relationships affect our behavior and brain development.

Fadi Issa joined the ECU faculty in 2014 after a postdoctoral stint at UCLA.

“We’re trying to understand how our social interactions with friends and colleagues shape who we are at the nervous-system level,” Issa said. “We’re asking, ‘How do our social interactions and our place within our social structure shape our brain functionally, morphologically and chemically?’

“We’re social animals,” he said. “Some of us have more dominant personality traits than others and some of us are higher up on the social structure ladder than others. We behave differently depending on who we interact with. The differences in these behavior patterns are not simply behavior manifestations, but they have physiological bases as well.”

Zebrafish make an ideal animal model for the study, Issa said, because of their similarities to humans and because of the way their bodies develop.

“Zebrafish are highly social and form social structures like humans do,” Issa said. “If you put two male zebrafish in a tank, they begin to aggressively duke it out. They chase and bite one another, but in a day or two, they form a social relationship and it lasts for a long time. Humans create these same types of relationships.

“Additionally, the fish are vertebrates and have similar brain structures to humans,” he said. “We can test certain neurological circuits in the fish’s brains that we have as well. Their brain and its development are easy to detect and study since they are translucent when they’re first born, allowing us to probe how the brain changes from birth to adult development.”

Issa’s research lab – which includes doctoral student Katie Clements, who gathered much of the data used for the grant proposal – will specifically look at how the brain adapts functionally and morphologically to changes in social condition over time between dominant and submissive zebrafish.

“In the case of zebrafish, we see a big behavioral difference between animals of different rank,” Issa said. “Over time, we’ve noticed that a fish’s motor behavior becomes quite different. In dominant fish, we see that they swim a lot, while submissive fish seek a corner and stop swimming. Conversely, submissive fish startle more readily compared to dominants. We are motived to understand the neurophysiological changes that take place as social relationships among animals mature over time.

“We also want to look at specific regions within the zebrafish brain which are also found in humans – including the hypothalamus – to see what developmental changes, if any, occur between dominant and submissive fish,” he said. “In other animal studies, these regions have been affected under stressful conditions and their growth has been limited. In mice, it has been found to lead to an inability to learn new tasks. We want to know if these changes happen across species and, if so, what are the implications and consequences for humans and their brain’s development.”

Issa said his research findings could contribute to understanding how the human brain adapts to changes in social conditions and determine how our brains respond differently to social stress.

“Stress plays a key role in social interactions, whether it’s in fish or humans,” he said. “These situations lead to changes in dopamine and cortisol levels and may lead to digestion and stroke risk. We want to understand the medical implications of what’s happening during these interactions, as well as the biological relationship and what happens to our nervous system because of the relationships we forge.”

Cindy Putnam-Evans, associate dean for research for Thomas Harriot College of Arts and Sciences, said that Issa’s research could have a big impact on learning how the human brain develops.

“Dr. Issa’s research on social behaviors and neurological connections in zebrafish, and the potential link to human brain development, is groundbreaking,” Putnam-Evans said.

Read more about Issa’s lab and his team’s research online.