TREATING ITP

Drug studied at ECU gets FDA approval

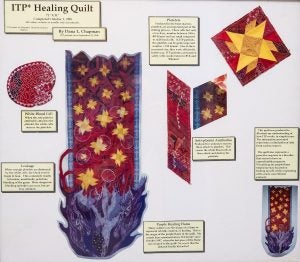

ECU hematologist/oncologist Dr. Darla Liles has a framed version of this quilt, which illustrates how ITP works.

The Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University took part in the study of a new drug recently approved by the FDA to treat a bleeding disorder.

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or ITP, is a rare disorder that results in a low number of platelets in the blood by creating antibodies that attack and destroy healthy platelets. Platelets are needed to help blood clot.

Symptoms of ITP include excessive bruising, bleeding from the gums or nose, blood in urine or stools and superficial bleeding into the skin that appears as a rash of reddish-purple spots, called petechiae.

ECU hematologist/oncologist Dr. Darla Liles, who directs the hematology/oncology division’s clinical trials office, said patients with unmanageable ITP have historically had limited medical options available to help them treat their conditions, including spleen removal or prescription medications that often cause severe side effects.

“Compared to breast cancer and lung cancer, ITP is relatively uncommon. But it definitely impacts our healthcare dollars because the people who have it are in the clinic very frequently and in the hospital more often,” Liles said. “So when we can take these diseases that have a high health care burden and make them just chronic illnesses where you can see them in the clinic only every few months, it’s a huge impact.”

This is why Liles spearheaded ECU’s involvement in the study of a new drug, fostamatinib, that looked at the drug’s effects on patients who had already exhausted other common treatment options but still had ITP.

ECU was one of only 53 sites throughout the United States and Europe to take part in the study, which included a total of 123 patients. More than two years later, ECU patient Raynelle Phipps is one of three patients in the United States – and one of 42 globally – still responding to the treatment.

‘In and out of the hospital’

ECU patient Raynelle Phipps had positive results from a trial drug that was recently approved by the FDA to treat ITP.

Phipps, a 41-year-old mother and teacher from Macclesfield, was diagnosed with the disorder in her 30s.

“About 10 years ago, I went to the emergency room because I had this rash on my leg and thought I was having an allergic reaction. That’s when the doctor told me I had ITP, because I had this petechiae blood coming out of my legs,” Phipps said. “I had no other symptoms, so it was really scary because I had never heard of ITP before.”

When medication alone could not treat her ITP, Phipps underwent a splenectomy, which was still not enough.

“I was in and out of the hospital, and missing days from school. I was being admitted for months at a time, because it seemed like whatever medicine they gave me, my body wouldn’t respond to it,” said Phipps, whose husband, Carl, took on a second job to help their family compensate for the increased medical expenses.

“I would get on a new medication, then a couple months later my body would deteriorate and I would start bleeding again,” she added. “I felt like I would never get well, that this would be my whole life – going in and out of the hospital.”

‘A sense of freedom’

Two years after agreeing to take part in the trial – a decision she attributes to “having nothing to lose” – Phipps says she is symptom free. Instead of having multiple appointments each week with Liles, she only visits every couple of months as a condition of the trial.

Her platelet levels have remained high, and her husband is back to working only one job.

What Phipps says is even better is being around more often for her children and students.

This year, she was named the Teacher of the Year at Princeville Elementary School.

“I’m very thankful that I was chosen to be part of this study, because since we tried it, things have been great,” Phipps said. “I’m just happier in general and I finally have a sense of freedom back.”

While Liles said she misses seeing the always bubbly Phipps as often as she used to, she is thrilled that she was able to have such a positive response to the drug.

She says this is only one of the many outcomes that exemplify why ECU is working to increase the number of clinical trials it makes available to patients in eastern North Carolina.

“Anytime we have a successful trial, it means that we’ll be able to get other studies available to us in a lot of different diseases,” Liles said. “It really gets your name and reputation out there, and makes you one of the leaders in new and innovative therapies.”