TICK SEASON

Stopping Lyme disease in its tracks

Researchers at East Carolina University, with funding from the National Institutes of Health, have declared open season on the bacteria that cause Lyme disease.

While rarely fatal, Lyme disease can be highly debilitating, said Dr. MD Motaleb, associate professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at ECU’s Brody School of Medicine. It can cause skin rashes, arthritis, neurological disorders and cardiac abnormalities.

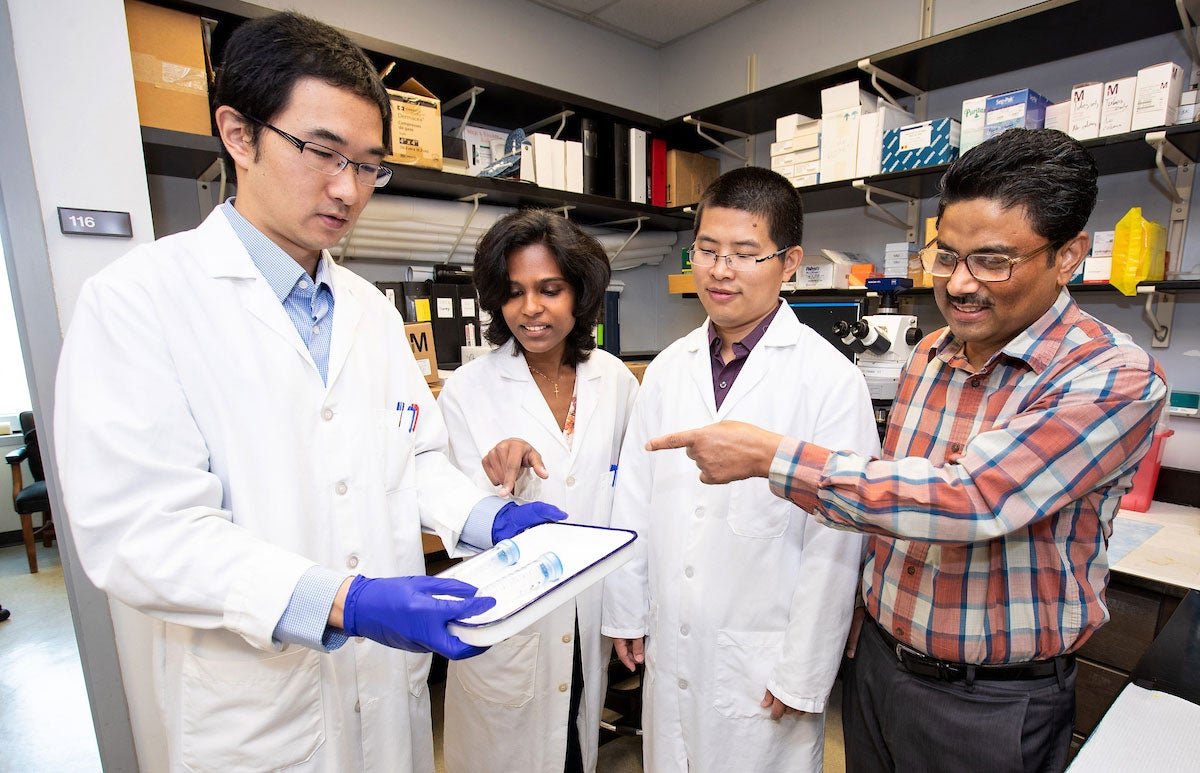

Zhou Yu, left, Priyanka Theophilus, Hui Xu and Dr. MD Motaleb, associate professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, are studying the bacteria that cause Lyme disease.

The disease is caused by bacteria that are most often transmitted to humans by tick bites. The ticks are small, Motaleb said, but size does not matter. One tick can transmit enough bacteria to produce the disease.

Ticks — and the bacteria they carry — have spread to new areas, catching rides on hosts such as deer. The study of the disease has been identified as a priority by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the NIH. State health departments reported 26,203 confirmed cases and 10,226 probable cases in 2016. Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control suggests that the number of people diagnosed with the disease each year could be as high as 300,000.

In order for the bacteria to survive in the host and be transmitted to new hosts, they have to be able to move, so Motaleb and his team — graduate student Priyanka Theophilus, postdoctoral researcher Dr. Hui Xu and research specialist Zhou Yu — are working to understand how the bacteria move and how to stop them.

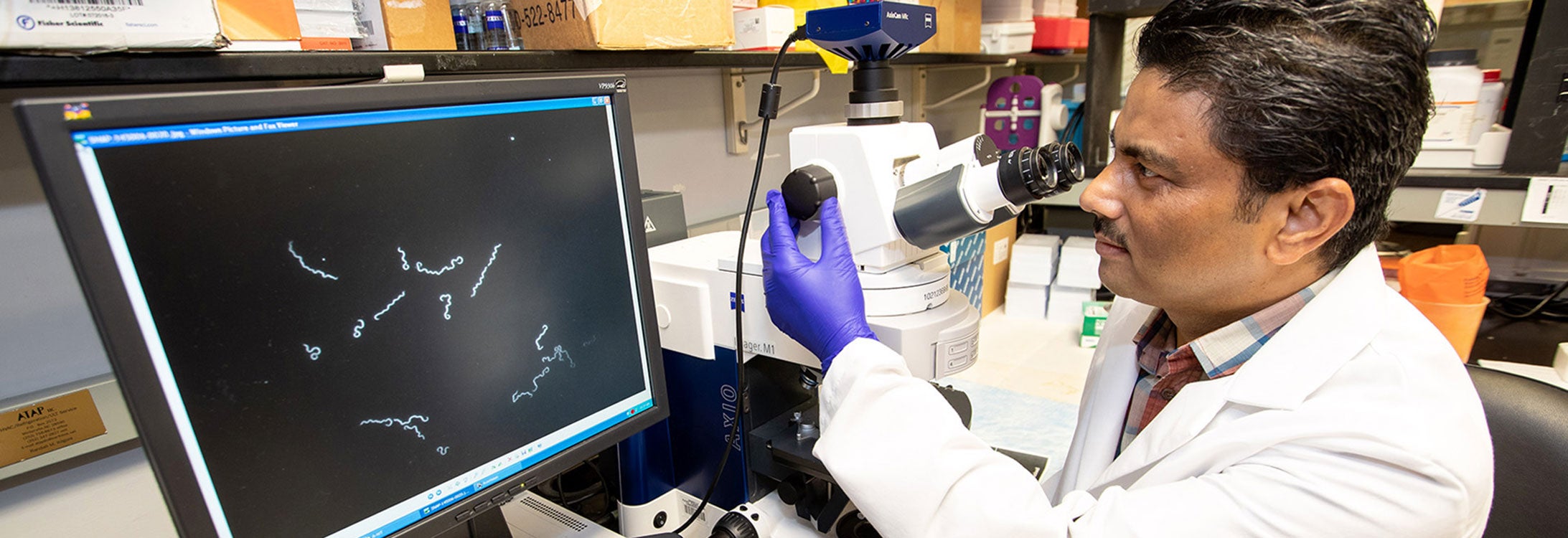

Bacterial motility — their ability to move — relies on flagella, whiplike appendages that protrude from the body of the bacterial cells. With the help of a new $1.69 million grant from the NIH, Motaleb is looking for the genes that make up a special unit of the flagella that enable bacterial motility. Since joining ECU in 2008, Motaleb has received more than $5.15 million in NIH grant funding, including approximately $1 million for his collaborators.

“Certain genes are responsible for their movement, and when we knock out those genes they become immotile — they cannot move,” he said. Ultimately he hopes the work could lead to the development of an antibacterial agent. “If we have a better idea of the physiology of the bacteria, we can someday develop an agent that can inhibit the rotation of bacterial motors as a means to inhibit the diseases.”

It’s also possible that the same knowledge could be used against other bacteria that cause serious diseases such as syphilis or leptospirosis.

In the meantime, it’s tick season, and the best way to avoid Lyme disease is to be diligent in avoiding and checking for ticks.

“Make sure you have tucked your pants under your socks so that you don’t get ticks in the first place, and when you go on outings in the woods, hiking or biking, make sure you come back and check for the ticks,” Motaleb said. “They are very tiny and hard to detect.

“It takes about 24 hours to transmit those bacteria from the tick to a human, so if you find them immediately and get them off, the chances (of infection) are very low.”

In the event of a tick bite, monitor for symptoms such as skin rashes, fever or headache, and if you have them, make sure you see a doctor, he added.

For more information on Lyme disease, visit https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/lyme-disease.