GROUNDED IN HISTORY

Field school identifies Pamlico Sound mystery wreck

With little to go on but fragments of oral history and the scant clues they could glean from a decaying steel hull, a team of East Carolina University maritime studies students has helped piece together the identity and story of a shipwreck in the Pamlico Sound near Rodanthe.

The project was made possible by the N.C. Department of Transportation, said Dr. Nathan Richards, associate professor of maritime studies at ECU and head of the Maritime Heritage Program at the UNC Coastal Studies Institute. Because the site could be disturbed by the Bonner Bridge replacement project, the DOT needed to determine the historical significance of the wreck.

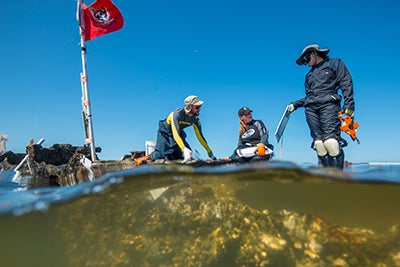

Dr. Nathan Richards provides oversight while ECU graduate students draft a site plan of the wreck.

The bridge construction created an opportunity to carry out an educational program that would teach students how to record a shipwreck using a variety of techniques and technologies as well as introduce them to the regulatory and legislative aspects of such a project, Richards said.

“As an archaeologist, I feel it is necessary to study and document these sites because they are representations of our collective past,” said graduate student George Huss. “This site, in particular, also offers an excellent opportunity for the public to learn about North Carolina’s rich maritime heritage.”

Field School

And so the team set to work in September on a month-long archaeological project to document and map the 150-plus-foot wreck, known as the Pappy’s Lane shipwreck, located on the sound side of the Outer Banks. Richards led a team of nine students as they created a detailed map of the site and conducted historical research to identify the potential history of the wreck.

The location of the site was both a boon and a curse for the field school, Richards said. Its proximity to shore meant it was fairly accessible. Working in shallow water, students had to immerse themselves, alternating between standing and swimming. Dive equipment was needed as the site was excavated, increasing the water depths. Visibility was also limited at times. The team recorded measurements on waterproof mylar sheets.

“Every morning we had meetings where each group was assigned a portion of the shipwreck to map while on site,” said graduate student Samantha Bernard. “The sections were broken up into five-by-ten (foot) portions.” Those sheets were combined at the lab into a scaled drawing of the entire vessel, ultimately comprising 177 drawings.

A number of local stories swirled about the wreck. One held that it was a Great Lakes steamer, another a dormitory barge from the Works Progress Administration era. The most persistent was a story about a gravel barge that grounded in the 1960s. That fit with the timeframe for the wreck, which begins to appear on nautical charts and in aerial photographs from the late 1960s.

“The problem with the gravel barge story,” said Richards, “is it doesn’t look like your classic idea of a barge.”

The wreck is long and fairly narrow, and it doesn’t have the wide, flat bow and stern of a purpose-built barge. “It could still be a barge, but it was probably not built as a barge,” Richards said. “Ships get transformed for various purposes throughout their lifespans. I felt there was another layer of history here that had been forgotten.”

There were numerous dead ends. A lot of time was spent looking at blueprints and photographs of Coast Guard buoy tenders, but ultimately, none of the vessels used for that purpose matched the few construction details the team could identify, such as the spacing of the hull’s framing. Aerial views of the site show a deck with hatches, but the configuration of the deck was unlikely to be original.

“One moment that stood out from the entire experience was when [Richards] found diagnostic features on the wreck that aided in the identification of the vessel,” said graduate student Paul Gates. “Located at the stern, the diagnostic features are called skegs and are engineered to house dual propellers within a vertical projection of the keel. Aside from protecting the propellers and rudders, the skegs allowed the vessel to operate as an amphibious assault craft that could be beached to deliver infantry or serve as a heavy fire support platform.”

The landing craft were used primarily in the Pacific Theater during World War II. Two types of ship used a similar hull. The Landing Craft Infantry, Large, Mark 3 (LCI) was used to land men on beaches using ramps from the bow. After early results showed that more support from other ships was needed for the landing craft, the heavily armed Landing Craft Support, Large, Mark 3 (LCS) was built.

Other features of the wrecked hull, especially at the stern, matched up perfectly with LCS-102, a preserved example of the craft located in Mare Island, California.

Second Life

The team continued to work, attempting to narrow down which of more than 923 LCIs and 130 LCSs that were built during the war might have ended up in the Pamlico Sound. They crossed off hull numbers that had been destroyed in combat or sold into foreign navies. Many of the remaining ships were eventually sold as surplus, and one in particular is likely to be the Pappy’s Lane shipwreck.

ECU graduate students map the stern of a shipwreck in the Pamlico Sound.

LCS-123 was sold to the Hunt Oil Company in Hampton, Virginia and was modified for use as a tank barge to haul heating oil and diesel for distribution, a clue that fit with something the students had noticed.

“The few days that I worked in the trench in the center of the vessel I noticed a petroleum smell, and my dive buddy noticed a sheen on the water,” said Bernard. “At first nobody else could smell or see what we did, but later on, after the biologist was reviewing core samples, she also noted the smell, so we had confirmation that a petroleum product may have once been onboard this vessel.”

Also of note is that LCS-123, which became Hunt Bros. No. 10, falls out of registration in 1965, which fits the timeline of the Pappy’s Lane shipwreck. Other circumstantial details from a surviving member of the Hunt family, including a description of modifications to the deck, further support the team’s theory of the wreck’s identity.

After identifying LCS-123 as a probable candidate for the origin of the wreck, the team was even able to track down photographs and a diary of members of the crew.

Further investigation of the local oral history revealed that there were actually two gravel barges that had gone aground near the Pappy’s Lane site. They were eventually floated and removed from the site, but a third vessel brought in to help with the salvage effort also grounded and was never removed.

As is often the case, Richards said, there was a kernel of truth in one of the legends that had survived the decades, but there was more to the story.

“The experience goes to show that our understanding and theories of archaeological sites are always subject to change, adding to the challenge and mystery of studying our past,” said Gates.

Richards presented the team’s findings during a public lecture at CSI’s facility in Wanchese along with Matt Wilkerson, archaeologist with the N.C. DOT. The work, Wilkerson said, determined that the site is eligible to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and now that the site has been thoroughly examined and documented, the construction of the bridge can continue.

East Carolina University is the administrative campus for the UNC Coastal Studies Institute, which was founded in 2003 and includes member institutions Elizabeth City State University, N.C. State University, UNC-Chapel Hill and UNC-Wilmington, as well as ECU.