WHY PEOPLE SMOKE

Studies explore smoking behaviors

Two years ago, East Carolina University psychiatrist Vivek Anand documented adolescent use of and opinions on electronic cigarettes. Now, he’s pinpointing the mechanisms behind smoking behavior.

Anand’s 2015 findings showed 15.2 percent of survey respondents had tried e-cigarettes, and 7.4 percent had smoked one during the 30 days before the survey. Sixty percent of students surveyed thought e-cigarettes were completely safe or posed minimal health hazards.

“We presented that study nationally and internationally,” Anand said. “We are also drafting a brochure for high school students and plan on distributing that through ECU Physicians clinics and Pitt County Schools.”

The brochure includes some of the study’s findings as well as facts and information about nicotine and e-cigarettes.

Since then, Anand’s interest in nicotine and tobacco use has continued. “We wanted to look at why people smoke, and why some people smoke more than other people, and what are the underlying mechanisms that drive smoking behaviors, or smoking cessation for that matter,” he said.

To that end, two new studies have begun, each funded by a Brody Brothers grant. The endowment was created by Hyman and David Brody to fund innovative research at ECU’s Brody School of Medicine.

One study centers on the differing responses of people’s brains to images related to smoking.

The first study is designed to pinpoint the correlation between how fast a person’s body processes nicotine and how much they smoke and to study the higher prevalence of smoking in patients with a history of mental illness.

“The hypothesis is that if you’re a fast processor, or metabolizer, of nicotine, you’re going to need your nicotine fix sooner compared to a slow metabolizer,” Anand said. “So that will reinforce your smoking behaviors. Nicotine being such an addictive compound, it is just going to make your behaviors more nicotine dependent.”

People who have struggled with depression or even have a family history of it, as well as patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, are significantly more likely to be smokers than the general population, Anand said. The study will compare a group of test subjects with a history of mental illness to one without; both groups are smokers.

For the study, researchers will collect demographic information and data about their smoking behaviors. Then hair and saliva samples will be processed to measure the byproducts of nicotine to determine how fast the patients process it. Several departments across campus will help with the study.

“Family medicine is helping with recruitment, and chemistry and pharmacology are helping with analyzing the samples,” Anand said, and the Department of Biostatistics will run statistical analysis. Chizimuzo Okoli of the University of Kentucky College of Nursing is also collaborating with Anand on both studies.

Allison Danell, associate professor of chemistry, said several students at the undergraduate and graduate level are participating in the project under the direction of Kimberly Kew. They will use mass spectrometry equipment to analyze the samples.

Anand said he hopes to determine whether some people smoke more and have a hard time quitting because their bodies process nicotine faster, leading them to crave another fix sooner. And if so, are patients with mental illness processing nicotine faster due to genetic predisposition, medications or some other biological process?

The second study will look at the brain’s responses to visual stimuli related to nicotine and smoking using an electroencephalogram (EEG).

The hypothesis for this study, Anand said, is that “when patients have higher rates of smoking and lower rates of smoking cessation … they are responding to these visual cues in a different way. They look at a pack of cigarettes and they are selectively focused and motivated by that.”

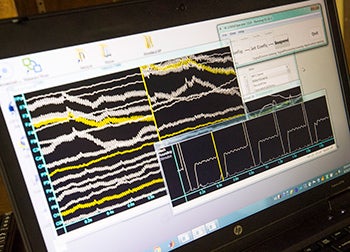

Study participants will wear an EEG cap and be presented with images of cigarettes and similar objects, such as a drinking straw. The Department of Engineering will help measure the EEG waveforms to study how people’s brains are responding to the target images versus the control images.

Both studies will help further the understanding of the mechanisms of nicotine addiction, potentially leading to better treatments to help people stop smoking. For example, Anand said, the failure rate for nicotine patches and gums are fairly high, and that could be related to faster processing of nicotine.

“If there is a treatment that could slow down the metabolism of nicotine, you could take that medication, and then the patch would be more effective,” he said. “There are a lot of innovative solutions that could come out of these two underlying hypotheses if they are true.”

It’s important to help people stop smoking because of the health implications, Anand said, since people who smoke are at higher risk of dying from heart disease, lung disease and other systemic problems.

“People with psychiatric disorders die, on average, 15-20 years earlier than people in the general community, and part of that is driven by higher tobacco consumption,” Anand said.

Current treatments such as patches, gums and counseling don’t work for everyone.

“We are losing a lot of time, they lose motivation, they become disheartened by the treatments we have to offer, and they fall off the treatment trajectory,” he said.

By offering better treatments and learning how to move to more effective treatments earlier in the process, he hopes to save time and benefit more people.

Anand hopes to provide a better understanding of smoking behaviors in order to improve treatments.