MODEL SPECIES

Worm found in compost valued for research

A tiny worm – nematode, technically – commonly found in compost has become a common subject for basic science and health science research, and forms the basis for several projects across East Carolina University’s campus that have received federal funding.

“Caenorhabditis elegans is a little nematode worm,” said Dr. Brett Keiper, associate professor in the Brody School of Medicine’s Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. “It’s not a parasite; it’s found in compost, and it’s found everywhere, on every continent. It’s about a millimeter long, thin and clear. And it reproduces like crazy.”

The little worm has earned three recent Nobel prizes for other investigators. The nematode’s reproductive cycle is part of what makes it a valuable model for research.

“It has a reproductive cycle that’s really a lot like that of higher animals,” Keiper said. “It reproduces sexually – it makes sperm and it makes eggs. … And the developing gametes are lined up in a nice linear fashion, start to finish. We observe the expression of proteins that make stem cells turn into sperm, eggs or even tumors when mutated.”

But each worm produces and fertilizes its own eggs – producing sperm in the larval stage and eggs as an adult.

“They make both gametes, one first and then the other,” Keiper said. “So we have the opportunity to look at clonal lines – every individual worm can make hundreds or thousands of copies of itself. That allows a lot of great genetics. If I make a mutation in the genome of one worm, I can pick an offspring from that worm and put it on a plate, and it’ll make a thousand new clones of itself.”

Lee and Dr. Brett Keiper discuss the traits that make C. elegans a useful model species.

It all happens fast, as the worms go from fertilized eggs to fertile adults in three days. Also helpful is that C. elegans’ entire genome has been sequenced; it was the first multicellular organism for which that was done.

When Keiper came to ECU in 2003, he was the only researcher using C. elegans as a model system.

“There are about five of us now, and remarkably – since federal funding is hard to come by – all of us have gotten some grants,” Keiper said.

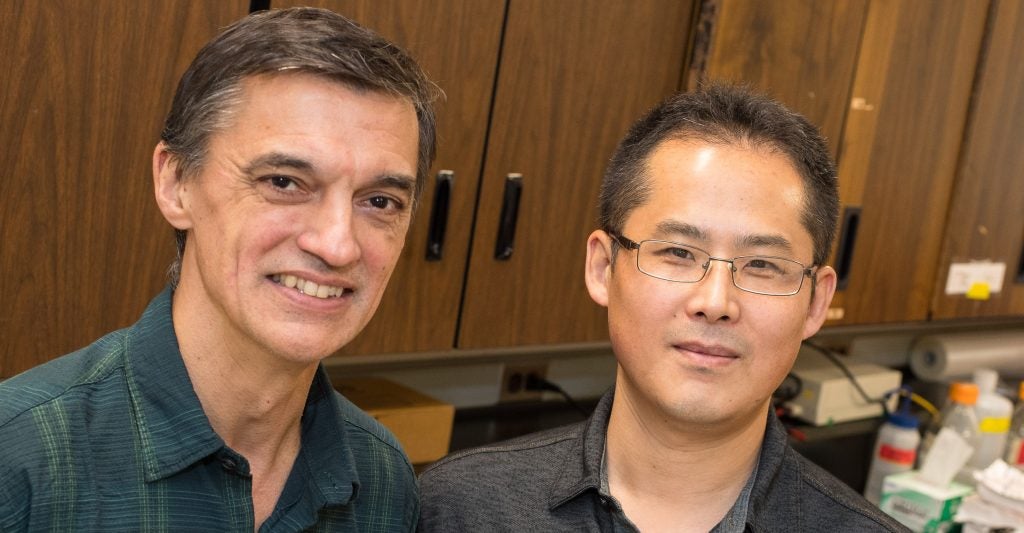

Keiper received a three-year, $635,000 grant from the National Science Foundation for his research on the mechanisms of protein synthesis. Dr. Myon-Hee Lee, associate professor of hematology and oncology, is a co-principal investigator on Keiper’s grant and also has a three-year, $367,000 National Institutes of Health grant for his own project, centered on cell fate decisions and how worms can be used as a model for tumor production.

“Embryos are really remarkable, the way that they develop into something that has all the various organs and features,” Keiper said. “What we’re looking at are the ways that those changes come about to make an embryo into a final organism – the types of proteins that make each cell unique, and how those cells become new cells.”

Both Lee and Keiper received Brody Brothers Foundation grants funding the preliminary work that led to their federal grants. C. elegans is also used on east campus, where Dr. Xiaoping Pan, associate professor of biology, studies how toxins affect embryonic development.

“It has many advantages,” she said, “such as a fully sequenced genome, a transparent body for microscopy observation of biological processes, short life and reproductive cycles, and large brood sizes.”

Pan’s research is currently sponsored by Cotton Incorporated and has also received funding from the Research Triangle Institute, NIH and NSF. Also in the Department of Biology, Dr. Baohong Zhang uses the nematode to study gene regulation and the Department of Chemistry’s Dr. David Rudel has been funded by the U.S. Geological Survey to evaluate the potential toxic effects of nickel exposure at environmental contamination sites.

Keiper said the researchers using C. elegans, as well as other model species such as mice, flies, fish and frogs, meet periodically to share ideas and collaborate.

“We each have a different focus in the reproductive sciences group – biology, chemistry, medicine, anatomy,” he said. “When we talk about the work we’re doing in our labs, you might hear, ‘I see something similar to that, but it happens this way.’ It gets us asking unusual questions of one another, and getting a different perspective than we’re used to.”

Ultimately, the research at ECU could lead to cancer therapies, better crop yields or treatments for infertility, Keiper said.

Dr. Brett Keiper and Dr. Myon-Hee Lee have received a National Science Foundation grant to study the mechanisms that determine cell fates in the reproductive system of C. elegans.