SHELTER FROM THE STORM

ECU helps communities recover from Matthew and plan for the next disaster

On Halloween, Jessica Parker worked near the corner of U.S. 17 Business in Windsor, shoveling gravel into potholes in a town park along the Cashie River, which had flooded a couple of weeks earlier.

The work meant something to her because Windsor is where her grandmother lives.

“I’ve got ties to Windsor, and they’ve been devastated so many times, I wanted to help,” said Parker, a junior child development and family relations major.

She was part of a group of faculty members, staff and students who have worked in Windsor and Princeville since the storm struck Oct. 8 to help recovery efforts. Another group plans to spend all day working in Kinston on Nov. 28.

In Windsor, the flood damaged or destroyed 100 houses and 56 businesses, said Mayor Jim Hoggard. Nearly 200 people were evacuated from their homes. It was the fourth time in 17 years – and the second time this fall – that severe flooding has struck the town.

Chris Locklear, ECU vice provost for academic success, carries diapers into a recovery center in Princeville on Nov. 8.

Stories were similar in other towns across eastern North Carolina – Tarboro, Kinston, Lumberton, Fair Bluff – as record rainfall inundated homes, businesses and government offices.

The storm took 28 lives – mainly through flooding – and caused an estimated $1.5 billion in property damage, according to state emergency management officials.

Hurricane Matthew emerged as a tropical wave off Africa on Sept. 22 and became a tropical storm in the eastern Caribbean six days later. It quickly intensified, reaching Category 5 status Sept. 30 – the first such storm in the Atlantic since Hurricane Felix in 2007. It made landfall in the U.S. on Oct. 8 as a Category 1 storm south of Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, then veered back into the Atlantic, dumping heavy rains from the state line to Raleigh.

Hard hit was Fayetteville, which received a record 14.82 inches of rain Oct. 8, topping the previous record of 6.8 inches during Hurricane Floyd.

In Greenville and Pitt County, however, Matthew’s effects were less than Floyd’s. Nearly 7 inches of rain were recorded at the National Weather Service rain gauge at the Tar River. The river crested at 24.5 feet, 5 feet below the record of more than 29 feet during Floyd.

Matthew created a 100-year flood for the area, while Floyd brought a 500-year flood. But those terms are deceiving.

ECU student Jessica Parker level gravel in a parking area at a town park in Windsor on Oct. 31.

“It’s not like clockwork – 100 years separating them,” said Scott Lecce, a hydrologist with ECU’s geography department, speaking at a panel discussion Tuesday.

Instead, those numbers mean a storm like Matthew has a 1-in-100 chance of occurring each year, and a 26 percent chance of occurring once every 30 years, Lecce said. Likewise, a storm like Floyd has a 1-in-500 chance of occurring each year.

Following Hurricane Floyd, the state, county and city worked to improve their flood zone mapping and used Federal Emergency Management Agency funds to buy between 260 and 300 properties in Greenville and Pitt County, creating green spaces and recreation areas. Most of those properties were in Greenville, totaling 162 acres north and south of the Tar River, said Anuradha Mukherji, an urban planning expert in the ECU Department of Geography.

While Matthew’s flooding was not as severe as Floyd’s, those measures helped contribute to less property damage. For example, 500-600 homes were damaged or destroyed as a result of Hurricane Matthew flooding, compared to 1,900 homes damaged or destroyed by flooding after Hurricane Floyd.

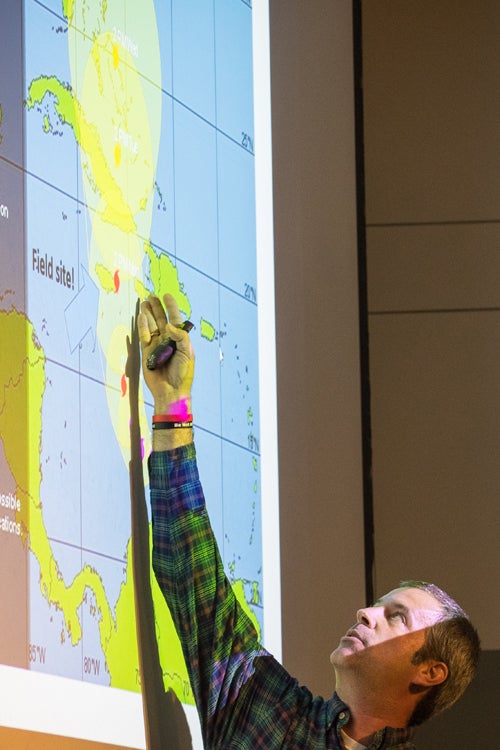

Dr. Scott Curtis, an ECU professor of geology, talks about Hurricane Matthew during a recent panel discussion.

In addition, Mukherji said, Greenville Utilities made improvements to its electricity and water-treatment operations in the wake of Hurricane Floyd. Partly as a result, those operations were able to continue during and after Hurricane Matthew.

In 2014, students in her emergency planning course put together maps and information detailing the impact of property buyouts following Hurricane Floyd. The information was used in developing the Neuse River Basin Regional Hazard Mitigation Plan, serving Pitt, Lenoir, Greene, Wayne and Jones counties.

Following a disaster such as a flood, she said, “the general tendency is to do something quickly and apply a technical solution.”

Rather than working to find ways to resist hazards, however, communities should find ways to be resilient, she said. That includes continued buyouts of property in flood zones and planning that takes flood hazards into account. “In the long run, it’s just better,” she said.

However, the drive to plan and resist development that exacerbates the effects of flooding can wane over time.

“The window of opportunity after disasters is three weeks to three months,” she said. After that, complacency sets in, and new people move to the area who have no direct knowledge of the event. Things get taken for granted.

But ECU officials hope through education and effort they can help towns recover and prepare for the next storm. That’s why Provost Ron Mitchelson spurred the workgroups. But for now, he’s not interested just in a string a slideshows and reports.

“After Floyd, I thought we had too many ties and not enough work gloves,” he said as he shoveled gravel into a washout in Windsor. “It’s not good when people show up, say we have help for you, then get back on the bus.”

A week later in Tarboro, city manager Daniel Gerald agreed. “We really appreciate all of the help and support,” he said. “The help you guys can bring makes people want to come back, and our citizens want to come back.”

Floodwaters cover the Green Mill Run Greenway on Oct. 11 following Hurricane Matthew.