SERPENT SPOTLIGHT

Snake experts convene for Venom Week V

North Carolina ranks first in the country for venomous snakebites, so East Carolina University was the perfect setting for Venom Week V, a conference on venomous creatures and the medical treatment of bites and stings.

Dr. Sean Bush, symposium chair and professor of emergency medicine, said North Carolina’s status as the epicenter for copperhead bites was part of what originally brought him to ECU three years ago. Six species of venomous snakes can be found in the state. This is where the most cutting-edge research in snakebites is being done right now,” he said.

(story continues below photo)

Dr. Sean Bush displays a copperhead and a cottonmouth at the live snake display in the Warren Life Sciences Building.

More than 250 experts in the field attended the conference, which was held March 9-12 at the East Carolina Heart Institute at ECU. The presenters hailed from ECU as well as other schools nationwide such as Duke, the University of Colorado and the University of New Mexico.

“It’s an opportunity for us to review the state of the art in envenomation medicine,” Bush said. “We want to encourage collaborations between the laboratory and the emergency room to continue to improve our medical treatments.”

Jennifer Styron, a pharmacist at Vidant Medical Center, said the conference introduced up-to-date information and gave her new insight into what happens to tissues and muscles after a snakebite, as well as how they are treated.

“We dispense CroFab (an antivenin) regularly, so it’s great to get to see the snakes and learn more about what happens,” she said.

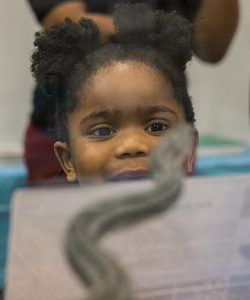

A visitor to the native snake display looks at a rat snake.

A collection of venomous and non-venomous snakes, spiders and scorpions was available for viewing during the conference, next door in the Warren Life Sciences Building. Dr. Dorcas O’Rourke, chair of the department of comparative medicine at the Brody School of Medicine, said she and her staff are dedicated to keeping both resident and visiting animals in excellent health.

“As a veterinarian I have had a long-standing interest in reptiles and amphibians,” she said. “It has been great to participate in the conference and to have the opportunity to display our animals.” O’Rourke noted the diversity of presentation topics at the conference, which included a session involving the treatment of snakebites in animals.

Dr. Eric Toschlog, professor of surgery at the Brody School of Medicine and trauma director at Vidant Medical Center, presented a keynote speech on the medical treatment of snakebites in humans, emphasizing the use of antivenin first, and using surgery only when absolutely necessary.

Because snakebites exhibit similar symptoms to compartment syndrome, in which excess pressure builds up in an enclosed space in the body, surgical means are often used to reduce the pressure. Snakebites can cause compartment syndrome, he said, but it is rare, occurring in less than 5 to 10 percent of cases.

Surgical means such as fasciotomy – cutting to relieve pressure in an area of tissue or muscle – are probably overused, and can create complications that may be unnecessary, he said. “Antivenin should be given first, and if compartment pressure is high, prepare for operating, but if antivenin brings the pressure down, don’t cut.”

For the public, Bush advised several safety practices. The first is awareness, as many bites occur when people aren’t paying attention to where they’re putting their hands or feet. It’s especially important to be cautious with the arrival of warmer weather, when both humans and snakes are becoming more active outdoors.

Second, if bitten, call 911, he said. Home treatments such as sucking out the venom are ineffective, and professional medical care is important if the bite is venomous. If possible, a picture or description of the snake or spider can help medical personnel determine the best course of treatment.

“Snakes are dangerous, and there is a fine line between fear and fascination,” Bush said. “I think that’s what makes people curious. When you are knowledgeable about something, you are prepared and you fear it less.”