REFLECTING HISTORY

Digging into diversity at N.C. heritage sites

One East Carolina University student’s research could help museums, plantations and Civil War sites in ongoing efforts to present a balanced view of history and to attract more minority visitors.

Wilson Hoggard ’14 said he has always been interested in history and received his bachelor’s degree in history from N.C. State University. For his master’s thesis in sustainable tourism at ECU, he said, “I knew I wanted to do something with historic sites, and they typically struggle for money. So I questioned how they could attract more visitors. I wanted to find out how or why or whether they could bring in more African-American visitors.”

To research the subject for his thesis, titled “Diversifying Eastern North Carolina Heritage Sites: Tour Guides’ Perspectives,” Hoggard chose six sites — Somerset Place, CSS Neuse, Museum of the Albemarle, Historic Beaufort, the Port of Plymouth Museum and Hope Plantation. He visited each site, speaking to tour guides about whether and how they cater to minority visitors, the barriers to attracting minority visitors and what improvements could be made.

Wilson Hoggard’s research showed that eastern North Carolina’s heritage tourism sites could be doing more to attract African-American visitors.

With the notable exception of Somerset Place, he said, each site could be doing a lot more to represent the African-American experience as a part of the portrayal of N.C. history. The top five reasons given by the tour guides for low minority participation were a lack of representation, elitist perceptions, lack of knowledge or interest, fewer African-American travelers and admission fees.

“I was surprised that only Somerset Place incorporates the history of African Americans,” said ECU’s Christine Avenarius, anthropology professor, who was Hoggard’s thesis chair for the project. “The other sites have the opportunity to do so in the future. I was also surprised how little advertising is done for these heritage sites. They should be promoted more at schools and community organizations.”

At Somerset Place, thanks to the efforts of former site manager Dorothy Spruill Redford, there are presentations and exhibits representing the lives of the slaves who lived on the plantation. A series of Somerset Homecoming events beginning in the late 1980s reunited the descendants of the slave families, and some of them continue to hold annual family reunions at the site, said Karen Hayes, historic site manager.

“Somerset Place was one of the first sites in the state to do an interpretive focus on the enslaved population of the plantation,” she said. “We try to reach out through our programming.”

In 2014, N.C. State students performed a dramatic interpretation based on N.C. slave narratives at the reconstructed slave homes on the plantation. Traveling exhibits of the 13 amendments of the U.S. Constitution and the Emancipation Proclamation have been displayed, and Somerset is also part of the National Park Service’s Underground Railroad Network to Freedom, a listing of sites that played a role in the efforts of slaves to escape their bondage.

“We have some visitors who come in just to see the site because their families were connected here, and they’re interested in researching the ancestry of their people,” Hayes added.

The rest of the sites, however, lacked significant exhibits and programming related to the African-American experience, Hoggard said.

“All of the guides from every site suggested that adding exhibits and programming focusing on African-American heritage would be beneficial in increasing participants,” he noted in his research findings. A common script for all tour guides would be a good start, he explained, since the content of each tour otherwise depends on the guide’s own interests.

Hoggard acknowledged that funding could be a major barrier to creating new exhibits and better staffing. Along with better scripts and exhibits among the short-term and long-term initiatives, his research suggests reaching out to children in schools, partnering with local universities, hosting traveling exhibits and hiring more black staff members.

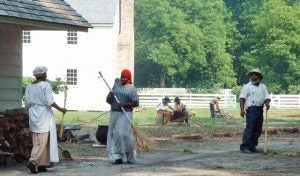

Both the plantation house and slave quarters at Somerset Place are used for historic reenactments. (Contributed photo)

“One place that the differences really stood out was in the gift shops,” Hoggard said. “Somerset Place had 38 different books on slavery; the next highest number was eight.”

Jeff Bockert, east region supervisor for N.C. Historic Sites, said that many of the sites are increasing efforts to incorporate programming and exhibits that include the African-American experience. Somerset Place, along with Historic Stagville in Durham, are unique in that they include both the plantation home and the slave quarters, which provides an opportunity for interpretive scenes.

“We try to have programming experience for everybody who’s associated with the site,” he said. “An important part of historic sites is that we’re for all of the people of North Carolina. We present themes and programming that relate to everybody who comes and visits regardless of their background.”

For example, he added, Historic Edenton is adding new interpretation of the urban experience of the enslaved population. “We hear a lot about slaves in the plantation setting,” he said, “but this will include the urban setting as well.”

Hoggard is now a teacher at Lawrence Academy, a private school in Bertie County. With help from Avenarius and his other advisor Carol Kline, who now teaches at Appalachian State University, he has prepared the thesis as an article with the hopes of publishing it.

“Historic reflections should strive to portray all the different aspects of human life that contributed to events and changes over time,” Avenarius said. “Hence it is important to include the voices of people whose ancestors arrived in North Carolina from other places than Europe. Learning about the historic developments can bestow a sense of belonging and significance and pave the way for mutual understanding and cooperation in the present.”

Somerset Place in Creswell, pictured below, includes permanent and traveling exhibits related to slavery and African-American history. (Contributed photo)